The End of Inflation in the US?

The official June inflation data came in below expectations, potentially signaling the end of the inflationary surge. What did we learn?

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. Please consider supporting us and sharing this article in various social media!

Introduction

A couple of weeks ago, the June Consumer Price Index (CPI), colloquially referred to as the inflation rate, was published (for an overview of what these measures are, please read our prior article here). The reported CPI came in below market expectations at approximately 0.2% month-over-month, and 3% year-over-year. Given the downward trajectory of inflation over the last several months, and the fact that 0.2% inflation per month is in-line with the Federal Reserve’s inflation target of 2%, many are suggesting that inflation is back under control. Moreover, a lively discussion has developed about what has brought this inflation down, with many claiming they were right. Let’s dig into what has happened, why it happened, what we learned and what is still confusing.

End of US Inflationary Surge

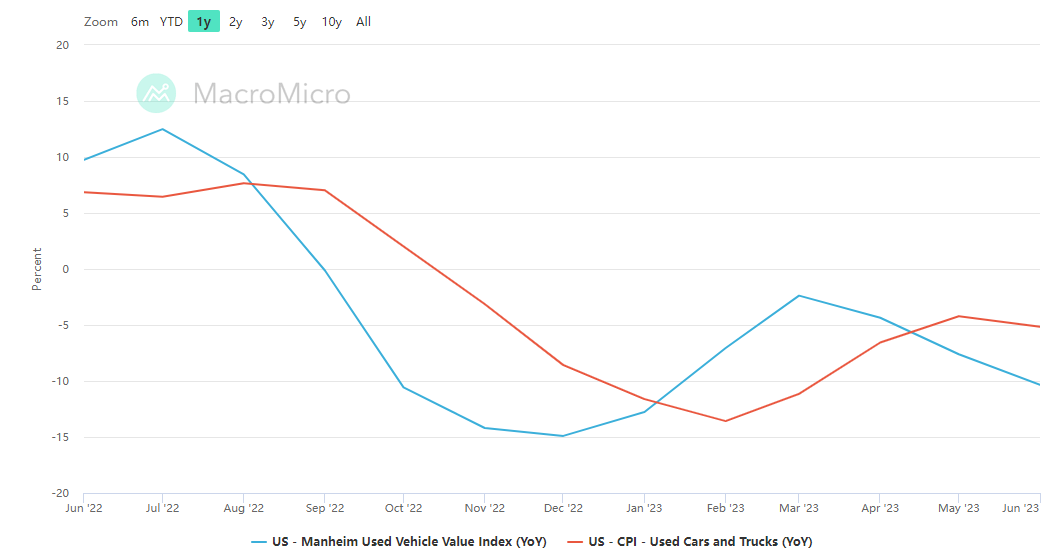

The 0.2% month-on-month reading is very promising. Moreover, there is a lot of evidence that this is not a one off data blip. Inflation will most likely continue to be in line with the 2% inflation target in July and August, as two of the largest sources of inflation – housing rents and used cars prices – are continuing to fall. Official inflation data actually tends to lag current prices a bit. For example, the used car prices collected for the CPI report via surveys tend to lag current data by two months. As real-time used car prices are lower today than a month ago, used car prices will reduce officially reported CPI in the next few months. The chart below shows the lagged nature of used car prices in CPI (red) against a more current price index, the Manheim used car index (blue line).

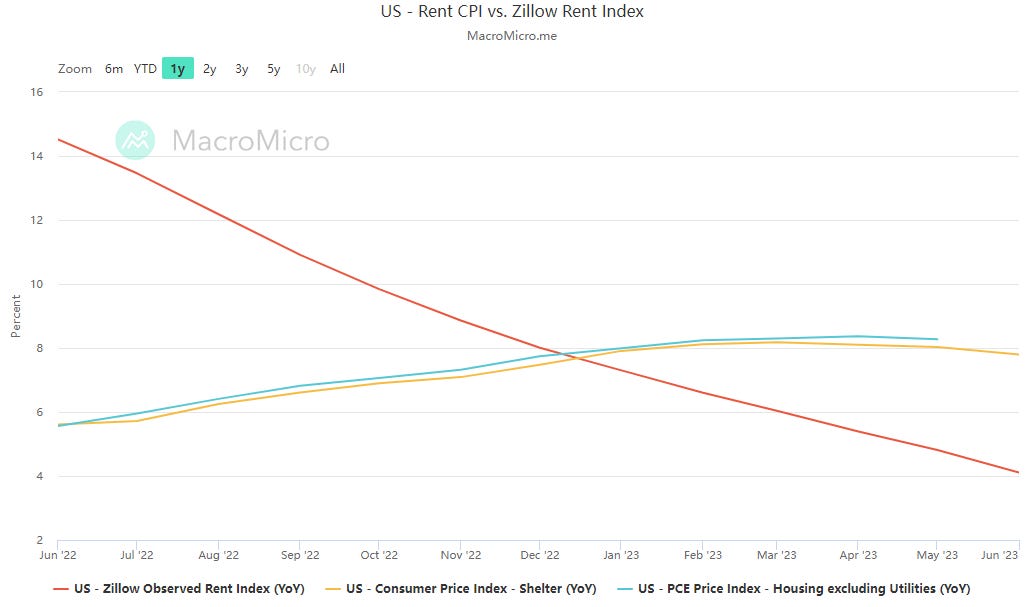

A similar pattern occurs with rent data in the CPI, as rents are set usually a year in advance. Additionally, CPI uses a statistic called Owner’s Equivalent Rent, which is a measure of rent for house owners. The idea is that even though you own the home, you are, in theory, renting this home to yourself. Since you could be renting it to someone else, living in your home is a cost as you are foregoing rent profit. Owner’s Equivalent Rent is an important measure but it has its issues (a great write up on this topic can be found here by fellow Substack writer, Dr. John Rutledge). Rents in the CPI measure are expected to continue to fall, thus further pushing inflation downwards. The chart below compares CPI rent (yellow) and the more current Zillow market rent index (red).

As inflation has come down, and appears to be nearing the 2% target, economists and commentators are discussing what led to this fall, especially without a recession occurring (yet), as many believed that a recession would be necessary to bring down inflation.

Let’s go over the main arguments and theories currently being discussed in explaining the recent fall in inflation.

The Theories

The increase in interest rates by the Federal Reserve

The easing of supply chain issues

Let’s go over each one, what are their strengths, weaknesses and what requires further questions.

Increasing Interest Rates

The main tool the Federal Reserve uses to bring down inflation is the Federal Funds Rate (colloquially called the ‘interest rate’). When interest rates go up, inflation goes down. Since interest rates went up to 5.25% from 1.75% a year ago, and the inflation rate fell in that time, from 9% to 3%, it seems logical that the raising of rates caused the fall in inflation.

Now, inflation doesn’t just fall because we raise interest rates. There is a mechanism behind how higher interest rates feed through into inflation. Raising interest rates makes capital (money) more expensive. So if you’d like to open a business or expand the business, it’s costlier. Since it’s costlier to start a new business, there’s lower demand for workers. Lower demand for workers means more unemployment (this is why we often hear that raising interest rates could increase unemployment). Higher unemployment weakens the bargaining position of workers in their salary and wage negotiations, meaning workers get paid less. If workers are paid less (and more people are also unemployed so they have no wages), they’re not able to afford goods and services. Firms have to respond by lowering prices (or not increase them by as much). This is the canonical mechanism of how increasing interest rates slows down the economy and, therefore, inflation.

The issue, however, is that this doesn’t appear to have happened. Unemployment in the US is very low at 3.6% (the average unemployment rate in the US since 1948 has been 5%). Real wages (wages adjusted for inflation) have not fallen (or not fallen by much), and have actually grown for many individuals, especially those with lowest incomes. Consumption spending has not fallen. Overall demand appears to not have slowed down (or not slowed down enough to warrant a fall from 9% to 3% in inflation), as US Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth remains very strong in the 2-3% range. This suggests that interest rates may not have been the cause of the fall in inflation, or at least interest rates did not impact inflation rates via the canonical mechanism described above. This has taken everyone by surprise – even the Federal Reserve was predicting higher unemployment rates than we are observing. If interest rates did bring down inflation, we need another story to explain the way in which it did.

As a brief aside, this is slightly concerning to me. The canonical mechanism described above is well established. The fact that this didn’t occur is great for workers right now, but the concern is what if it actually happens, but in a few months or quarters. Current interest rates are high, so it really is costlier to open businesses. At some point it feels like workers will be impacted, and this could lead to the recession many have been forecasting.

Another issue with the pro-interest rate argument, is that interest rates were also increased in other countries, especially in Europe. The UK has a similar interest rate to the US, but has inflation at 7.9%. Why would there be such a big discrepancy between the inflation rate in the US and the UK? Again, this would need to be explained.

Supply Chain Improvements

In this theory, the relaxation of supply chain issues resulted in a fall in the inflation rate. We have discussed this theory and model at length on Nominal News. I recommend reading a previous piece we wrote to get a full breakdown of the theory (which has puzzled many economists). Basically, the theoretical model, used by Central Banks, states that if the cost to produce is higher (note: if you have read my previous article, I’m referring to real marginal cost, which for simplicity I’m calling production cost), the inflation rate will be permanently higher. Supply chain issues during Covid-19 made production more costly (for example, shipping delays of computer chips means more time is required to build a car).

So have supply chain issues disappeared? A good overview of the current US supply chains can be found here by fellow Substack writer – Joseph Politano. The article goes over a wide variety of data showing the trajectory of a set of supply chain issues. The overall point can be best seen here:

Supply chain issues have dramatically improved from pandemic peaks, but they are still present as can be seen in the graph. As long as the production costs are higher (caused by supply chain issues) than pre-pandemic levels, the inflation rate will remain elevated. So it is not surprising that the inflation rate is currently still above the 2% target, based on what the chart shows above.1

The main issue with the idea that supply chain easing is behind the fall in inflation is testing the theory with data. We do not actually observe the production costs – we do not have any way of measuring them yet. We do not know how the production costs have changed over time. The chart I cited above is not direct proof of production costs falling (or rising). We only assume production costs have moved in tandem with how companies report their own supply chain issues (the graph is a good proxy for production costs).

Our victory lap?2

Based on the two main causes behind the inflation fall, it does appear like the biggest source of the fall was the supply chain improvements. Naturally, the increased interest rates also probably played a part in inflation reduction. As stated earlier, I am concerned that the high interest rates might actually push the US economy into an unnecessary recession, as the impacts of the interest rates start working through the economy.

At the risk of tooting my own horn, we did focus a lot on the supply chain issues here at Nominal News (here and here) and argued that as supply chain issues ease, we will see the inflation rate continue to come down. This conclusion was primarily drawn based on the work of Lorenzoni and Werning (2023). Why did I think this work provided us with the best understanding of the current inflationary period? It was because of their model. In Part 2 of this article, I will discuss what makes a good model.

The Lorenzoni and Werning paper caught my eye, because it was a model that had many possible outcomes – it allowed for both interest rates rising to lower inflation, as well supply chain issues easing to do so as well. With both possibilities available, it could tackle both of the theories we discussed at the same time. That’s why it is a good model. Their model highlighted that if supply chain issues are actually temporary, inflation will fall, albeit slowly. That’s what I picked up on from their model and why I focused on supply chain issues at Nominal News.

Conclusion

Although I am currently leaning towards the notion that most of the fall in inflation can be attributed to healing supply chains, it is not definitive. As more research comes out in the next few years, hopefully the mechanisms and what caused inflation to fall can be better explained. Furthermore, it is important to view any opinions (even my own) on this topic through the lens of a model. This enables us to focus our discussion, avoid hot takes and improve our understanding of critical issues.

In the meantime, I hope not to have to write about inflation any more for a while, as I have focused a lot on this topic. If all goes well, there shouldn’t be any reason, although I do have a concern that we may have over-salted a bit, which could result in a recession.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Recession Indicator: The Conference Board Leading Economic Index (LEI), which is a combination of ten different economic data indexes (such as weekly work hours in manufacturing, number of new building permits, and consumer confidence) has shown a -9.9% reading. LEI has not been this low without being in a recession since the 1960s.

People with disabilities represent a record percentage of the labor force. I believe remote work has been crucial in this.

Article: Alice Evans discusses how automation and the industrial revolution has impacted the gender imbalance and influenced social norms, as well as the cause behind the pushback towards social change.

Article: Jadrian Wooten explains the economics behind the potential new Vehicle Miles Traveled fee and the newly proposed New York City congestion charge, and why these two solutions can help solve many issues including pollution and congestion, as well as encourage the green transition.

Cover photo by su vbp.

Wages and Inflation (December 4, 2022) – to what extent do wages cause inflation?

Work Requirements (May 29, 2023) – work requirements are considered to be a helpful policy to incentivize people to work. Empirically, the data shows that this is not the case. It does not increase participation in the workforce and hurts the most vulnerable individuals.

Housing – Will deregulation fix everything? (April 9, 2023) – would removing zoning laws and housing regulations lead to an increase in housing supply and improve housing affordability.

It is worth noting that raising interest rates can also impact the production costs. As mentioned in the interest rate section, the aim of raising interest rates is to slow down the economy, and reduce worker’s bargaining power in wage negotiations. By reducing worker’s wages, we reduce the production cost, as it is cheaper to produce now since labor is cheaper. However, as we discussed before and mentioned here, real wages have not really fallen though, and actually increased for many. Therefore, if production costs fell, it could not have been caused by falling wages, but rather must be other supply costs (shipping, reopening factories).

There are also a variety of other theories being suggested. We will briefly mention one – ‘greedlfation’. The idea here is that firms previously were able to get away with higher profit margin, but are no longer able to do so, resulting in falling inflation. We’ve discussed ‘greedflation’ recently and stated that it is grounded in economic theory, which states that due to supply chain disruptions, temporary monopolies formed, allowing these monopolies to charge higher prices. Although possible, and probably to some extent market power concentration did increase temporarily, it is unlikely to have caused such a large inflation surge and then drop, due to firms gaining market power and then quickly losing it. Moreover, similarly, inflation has persisted in Europe, which would suggest that in Europe, firms still have increased market power. Demonstrating this would require a lot of additional data.

Maybe the effect of raised interest rates on employment is less visible, because before raising them, the businesses were seriously understaffed? Meaning that maybe some jobs were lost due to raised rates, but they were 'virtual' - not taken by anyone. Is there a way to measure that?