Causes of Current Inflation

Recent conversations in the US and the World have focused on the very high inflation rates in many economies. What were the causes of this inflation surge?

Current inflation (or Consumer Price Index “CPI”), between 7%-8%, is far higher than the inflation of 2% targeted by Central Banks around the world. Many explanations have been given for this inflation surge - too much aggregate demand via stimulus checks, supply bottlenecks, wage increases, too loose Central Bank policy — to name a few of them. Previously, I discussed whether there is evidence that wages cause inflation (the colloquially named “wage-price spiral’), and concluded that increasing wages were unlikely to have caused the current inflation surge. Here, I will discuss what recent research has focused on as the key drivers of current inflation and whether we are measuring and thinking about this inflation surge in the correct framework.

Measurement Issues

First, it is helpful to discuss how inflation is measured and whether we are getting an appropriate picture of it. Inflation is measured by tracking the price of a ‘basket’ of goods. This basket aims to represent what an average consumer purchases, so it includes things such as food, transportation, housing, medical cost, energy, recreation, and other services. One key decision is how much weight to put on each of the categories. The weights of each of these categories of the US basket were last updated in December 2019, over a year before the Covid-19 pandemic. However, Cavallo (2021) argues that the pandemic drastically altered what consumers bought - for example, far more goods were purchased, while consumption of transportation fell significantly. Goods saw a much larger increase in price at the start of the pandemic, as people made a lot of purchases during lockdowns, while transportation became very cheap, as very few people were using it. Thus, the reported inflation rate might have understated true inflation for consumers, as their baskets changed because of restrictions.

Cavallo proposes an alternative measure (“Covid-19 CPI”), which suggests that inflation was understated in the beginning of the pandemic, while it is overstated now. The difference is significant – in mid-2021, the US inflation could have been overestimated by 0.7 percentage points.

The reason this measurement is important is that it can misinform policy makers as to what is driving inflation and whether a turnaround is occurring. Furthermore, because consumers may now have different consumption baskets from what the Federal Reserve assumes, consumers might have a different view on inflation expectations (i.e. what will inflation be in the future).

Trend or Noise?

Another important question around the current inflation surge is whether it has permanently impacted the trend of inflation or is it only a temporary surge. A permanent change is an issue for Central Banks, as it implies that bringing down inflation is much harder, while a temporary jump does not require much Central Bank intervention.

The main way the current period of high inflation can become permanent is through inflation expectations. Inflation expectations, as the name suggests, are what individuals and firms believe inflation will be in the future. During normal times, with a 2% inflation target, we would expect inflation next year to be 2%, and thus companies would, on average, increase prices by 2%, fulfilling the expectation.

Issues arise when actual inflation is decoupled from inflation expectations. With inflation currently at 7%, assuming that inflation will be 2% next year might not be correct. Thus, companies would adjust their prices higher than before, which in turn fuels the increase in inflation. Central Banks know this and therefore must convince individuals and companies that inflation will be brought down quickly to 2% (this is done via increasing interest rates,1 which is one of the main reasons the Federal Reserve has increased interest rates at record pace since March 2022). If elevated inflation persists, higher inflation expectations can become permanent, making it close to impossible for the Central Bank to bring inflation down. However, determining inflation expectations of individuals and firms is not an exact science and estimating them is not straightforward. Over-estimating the impact of inflation expectations can result in a Central Bank overreaction (i.e. increasing interest rates too much), which can negatively impact the economy by significantly increasing unemployment, and even resulting in deflation.

Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe (2022) attempt to address this issue by pointing out an important estimation problem. Economists currently estimate the permanent component (a significant part of which is inflation expectations) using statistical procedures on data starting after 1955 (post world war 2). During this time, inflation changes were rather slow moving. Using this data for estimation implies that the current permanent component of inflation has gone up by 2.38%. However, Schmitt-Grohe and Uribe argue that the recent inflation spike is unique relative to the 1955-2021 time period. Between 1900 and 1954, inflation tended to be much more volatile. By using the full data set from 1900 to 2021, the permanent component of inflation only went up by 0.51%. This is a very economically significant difference between estimates and would meaningfully impact the behavior of Central Banks.

Aggregate Demand

Although the above suggests that there are questions around correctly computing inflation and how much of it is permanent, it does not tackle the issue of what are the primary drivers of this inflation surge. One key source of inflation that is being studied is the impact of aggregate demand (the total amount of demand for goods and services). If overall demand for goods and services becomes greater than what the economy can supply, prices will go up to bring the economy into equilibrium, resulting in an inflationary surge. During the pandemic, many countries undertook expansive fiscal (by providing various forms of stimulus - checks, tax cuts, loans) and monetary (reducing rates, purchasing assets such as bonds and mortgage backed securities) policy to maintain aggregate demand. Over-stimulating the economy can result in inflationary pressures. In the US, the one-off pandemic fiscal stimulus during the Covid-19 pandemic was estimated to be over 25% of US GDP.

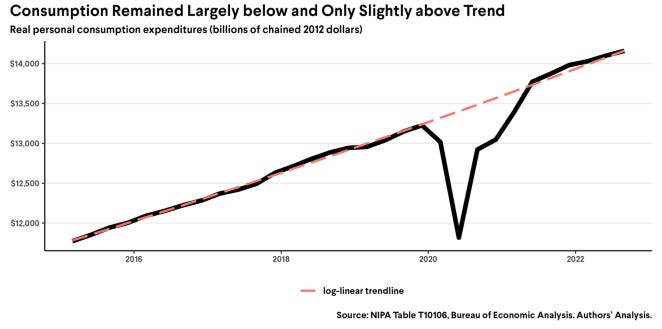

A recent report by Stiglitz and Regmi (2022) looked at how aggregate demand behaved during the pandemic. Consumption spending has largely followed the historic trend.

All other components of aggregate demand (investment, government expenditures and exports net of imports)2 are at or close to the historic trend. Furthermore, actual GDP is currently not above potential GDP3 (see chart below), which suggests that the economy is not overheating (growing faster than is sustainable). These results suggest that overall aggregate demand is most likely not responsible for the inflation surge.

Supply-Side Shock

The other competing theory is that this inflation spike is caused by supply side issues, which were mainly exhibited by production bottlenecks. Research by Cavallo and Kryvtsov (2022), found that product stock-outs and discontinuation during the pandemic contributed to significant inflation surges in the impacted industries. The authors collected data from a variety of online retailers and tracked whether a product was unavailable to be purchased. From this data, they were able to estimate the stock-out and discontinued product ratios.

Using this data, the impact of these stock-outs on inflation can be estimated. Their results imply that an increase in stock-outs from 10% to 20% resulted in an 0.1 percentage point increase in monthly inflation (approximately 1.2% annualized). Cavallo and Kryvtsov also find that the impact of stock-outs is transitory - it dissipates after three months, potentially reducing inflation pressures quickly. Certain sectors were impacted more heavily - food and beverage, and electronics resulting in higher inflation in those subsets, as the stock-outs were more persistent. Furthermore, the impact of these stock-outs was not noticed during the early part of the pandemic. Early in the pandemic, there was a significant drop in consumption (as can be seen in the consumption expenditures figure above), which would normally lead to a reduction in prices. However, stock-outs, which were very prevalent during the early phase of the pandemic, pushed these prices up. These two competing forces kept prices unchanged in the first months of the pandemic.

One more finding from Cavallo and Kryvtsov is that due to more transactions occurring online, prices can respond to inflationary pressures more quickly (economists call this “menu costs”4). Furthermore, as traditional brick-and-mortar retailers also compete with these online retailers, any shock, such as the online stock-out shocks, will feed rapidly through to these firms as well, further pushing nation-wide inflation.

Another paper that looked at the impact of supply-side constraints is di Giovanni, Kalemli-Özcan, Silva and Yildirim (2022). Unlike the other papers mentioned so far, this one focused on a theoretical model of the US and Eurozone economy, where they could jointly examine the impact of aggregate demand and supply-side shocks. Their main finding is that supply-side shocks accounted for 50% of the inflation in the Eurozone and 33% in the US during the 2020 to 2021 period. The rest of the inflation shock was attributable to the increased aggregate demand. However, the method of establishing aggregate demand in the paper is not estimated on data - it is rather selected to match what was observed in the data.5 Given the limited treatment of aggregate demand in the model,6 di Giovanni et al. mainly focus on the conclusion that the presence of supply side constraints had significant impacts on inflation and that this impact varied by country.

What’s Next?

On December 14, 2022, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 50bps, to 4.25-4.50%. The expectation is that the Federal Reserve will further raise interest rates up to 5% to 5.5%. Research by Blanco, Ottonello, Ranosova (2022) looked at inflation surges that occurred between 1990 and 2019 to establish certain empirical patterns. They found that disinflation (i.e. a reduction in inflation) took longer than the initial inflation surge (the inflation trajectory is described as an inverted or upside-down swoosh). Furthermore, inflation expectations are slow to increase during the inflation surge, but they do slightly go up and persist during the disinflation period.

During these inflation surge and disinflation periods, Blanco et al. (2022) found that Central Banks tend to respond slowly and real interest rates (nominal interest rates net of inflation) are not increased by much. This leads to the situation that inflation expectations increase, resulting in the prolonging of the disinflation period.

One weakness in the empirical data mentioned by the authors is that a majority of the data comes from emerging economies, which may have weaker institutions. Thus, the response to interest rate increases (“monetary tightening”) in developed economies might be different and more effective in bringing down inflation.7 Another issue with the empirical analysis is the time period selected. Research by Cavallo (2021), described above, suggested that the current inflation might be more comparable to the early 20th century, while Blanco et al (2022) focused only on data after 1990. The empirical patterns in both these papers stand in contrast, as the early 20th century data suggests inflation would fall much quicker than what data after 1990 suggests.

Conclusion

The current inflation surge that occurred during the pandemic appears to be very unique compared to recent decades. Many different theories had been suggested to explain it and the debate on how much each factor played is not settled. Based on the current state of research, the leading cause appears to be supply-side issues due to the Covid-19 lockdowns, which put inflationary pressures in specific sectors - food and electronics seemed to be most impacted, but the entire goods sector struggled to produce during the pandemic. Demand shifted from services, such as restaurants or entertainment events, to the goods sector, which further increased inflationary pressure. Aggregate demand itself does not seem to be very important as consumption has broadly remained in trend, while increasing wages appear to respond to inflation rather than cause it.

Going forward, the debate on how inflation dynamics will develop and how high interest rates should be is also not settled. The danger for Central Banks is increasing interest rates too high, leading to a recession. Not increasing interest rates sufficiently quickly or high enough can lead to a much longer inflationary period. The cause of the inflation is also important - if it is a supply side issue, increasing interest rates too high could further worsen these issues, as new firms will find it too expensive to open. Lastly, there is also the danger of mismeasuring the actual inflation rate by not adjusting the consumption basket, which could result in aiming for the wrong target by the Central Banks.

Given that supply side bottlenecks have been easing, it appears that inflation will drop in the US quite quickly. Between September and November 2022, the annual inflation dropped from 8.2% to 7.1%. Moreover, inflation initially reacts relatively slowly to interest rate increases, as the economy responds in a lagged way.8 The global easing of the bottlenecks will reduce supply side pressures, while a rapid increase in interest rates to a relatively high level will dampen goods demand (retail sales in November dropped at record pace). This will reduce all sources of inflationary pressures in the US economy quickly. The worry is whether the Federal Reserve has done too much and might push the US economy into an unnecessary recession. However, the recent increase in interest rates in December 2022 was originally expected to be 75bps, but the Federal Reserve decided to only increase by 50bps, suggesting that they are aware of this danger.

Increasing interest rates encourages saving money rather than spending it, as you can earn more in interest.

Aggregate demand is the sum of Consumption, Investment, Government Expenditures, and Net Exports, which equates to GDP.

Potential GDP is a measure that aims to compute what is the highest sustainable growth level of GDP. There is a lot of debate around how to accurately estimate this. Stiglitz and Regmi argue that actual GDP is below potential GDP.

The name menu costs comes from the notion that it is costly for restaurants to change prices constantly, as they would have to print new menus after each price change. Thus, prices generally do not adapt daily to inflation and market data due to the costs associated with undertaking this change.

In economics, this is called a calibration exercise, where you set parameters in your model in such a way that certain outcomes of your model, such as the inflation rate, matches what was observed with actual data.

Another issue is that to match the fact that work places such as factories were shut down and thus had a low amount of workers, the authors introduce an artificial limit on the labor supply available to these sectors, which results in much higher wages early in the pandemic that does not match the data.

The reason for this is Central Bank credibility - do individuals and firms believe that the Central Bank will do everything to bring down inflation to a specified target. The reason Central Banks might choose not to, is that increasing interest rates increases unemployment, which slows down the economy, making it a politically undesirable outcome.

For example, since firms typically make certain decisions many months in advance, they will only be able to react to increasing interest rates with a delay.