Inflation and Expectations

Inflation is being hotly debated again with recent worse than expected data releases. What does this new data mean and what is the Federal Reserve thinking?

Summary

New inflation data for the month of January came in higher than expected.

Multiple inflation measures exist, as each one gives a slightly different perspective on current inflation.

The Federal Reserve mostly focuses on PCE Core Inflation.

Although inflation has come down significantly, it is still well-above the Federal Reserve target of 2%.

Some of this may be driven by higher inflation expectations.Inflation may remain elevated until supply-side issues fully subside.

The Federal Reserve needs to consider waiting for supply-side issues to fully ease which may take a long while vs quickly bringing down inflation, risking a serious recession.

Introduction

During this recent inflation spell, we have covered what are the most likely causes of the inflation surge (supply side issues) and why wages are unlikely to be the culprit. This week, new data regarding inflation for the month of January was released. The mood from the media and commentators is that this data suggests that inflation is still ‘too hot’ and that the Federal Reserve will need to do more to tackle it. What is the current inflation situation, how is the Federal Reserve approaching it, and what are all these inflation acronyms?

Updates to the Data

In this section, I will go over the data that was released, what it means and how it is collected. If it is something you are aware of, I recommend skipping to the next section.

Inflation data gets reported every month. However, there are multiple measures of inflation that are reported and each of them represent something slightly different. Let’s take a look at the measures:

Consumer Price Index (CPI) – this is what is most commonly referred to as the inflation measure. It is usually announced soon after month end in the US. CPI is measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The CPI measure focuses only on urban populations and their out-of-pocket expenses. The CPI measure is created by conducting a survey of consumers, asking them where and how much they spent on buying certain goods. The goods on which the CPI focuses are pre-selected earlier, using a so-called typical ‘basket’ of goods. This basket is fixed for a period (typically 2 years). This creates an issue – it may occasionally overestimate the true increase costs, because it does not take into account substitution effects – for example, if apples become expensive, consumers might buy more oranges instead. Their overall spend on food might remain the same (no inflation), but CPI will show an increase in price because of higher apple prices.

Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index (PCE, or more accurately, PCEPI) – this is an inflation measure constructed by the Bureau of Economic Advisors (BEA). This inflation measure is more often used by the Federal Reserve when making policy decisions. The PCE collects spending data from both urban and rural populations. It also looks at expenditures conducted by third-parties on behalf of consumers – for example, health-care spending undertaken by employers. The last key difference between the CPI and PCE is that the ‘basket’ of goods used for this measure is constructed based on surveys of businesses and what they sold in the current month. This basket, therefore, can fluctuate rapidly. This is then used along with the survey data on out-of-pocket expenses collected by the CPI. This measure deals with some of the issues of the CPI, as it can capture the fact that people substitute goods. Another benefit is that the ‘basket’ is more likely to be a true representation of what goods were sold during the prior month. Consumers may under-report how much they spend on ‘vices’ such as alcohol and tobacco in surveys, while businesses have no incentive to give false data. The main drawback of the PCE is that it takes much longer to collect accurate data. Even the first PCE release, which comes nearly a full month after the CPI data, can end up being amended later.

The differences in what CPI and PCE place weight on are quite significant – below is a list of the largest differences (Source: BLS):

CPI weighs housing and rent expenditure much more than the PCE. On the flip side, the PCE puts far more importance on health expenditures.

Now to further complicate issues, CPI and PCE are sometimes presented in their ‘Core’ version. Core CPI and Core PCE strips out energy and food spending from the basket, and therefore they are not included in the inflation measure. The reason for this is that both food and energy can be very volatile month to month. In the past year, both food prices and energy had dramatic jumps. This can heavily distort the inflation measure. It is worth noting that energy still impacts the other categories of inflation, because you need energy to produce and transport goods.

Recently, another measure has made the news – “supercore” inflation. Supercore inflation is not an official measure. Its key difference from CPI and PCE, is that it strips out food, energy and housing. Thus, it is Core Inflation without the impact of housing.

Lastly, there are two more measures that have been commonly referred to recently – Producer Price Index (PPI) and Employment Cost Index (ECI), both measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The PPI is very similar to the CPI, but instead of asking what consumers paid for goods, the surveys ask producers how much they received for their goods and services. The reason the CPI and PPI responses can differ is that the price paid for by a consumer does not have to equal the price received by the producer. Government subsidies can reduce prices for consumers, but producers receive a higher amount. Thus, this can create distortions in measuring actual inflation – a government could easily reduce inflation just by offering subsidies, but the underlying price of the goods does not change. For example, in recent months in Europe, many governments have subsidized energy bills for consumers. This lowered reported inflation (CPI), but had no impact on the actual energy costs. Other factors that can lead to CPI and PPI differences are producer taxes and distribution costs. The ECI tracks the change in the costs of labor, allowing the Federal Reserve and US government to get a better picture of wage growth. All of these are additional measures that can give a better picture of the overall economy and the trends in prices.

Data Concerns

It is worth noting that most of the data for inflation comes from some form of survey data. The validity of these measures, therefore, relies on the quality of the collected data. As surveys can be unreliable, this explains the reason why there are so many different ways of collecting the same data – CPI, PCE, PPI, ECI. One significant issue, however, that is not easy to deal with is the lack of response to surveys. When an individual or a firm chooses not to respond to a survey request from the BEA or the BLS, it is not an innocuous decision. If there is a particular reason why certain firms or individuals do not respond to surveys, data can be skewed leading to a misinterpretation of what is happening in the economy. Recently the no response issue has significantly worsened. Data shown by Apollo Management shows a dramatic fall in responses.

This is a concern that is difficult to mitigate.

Dealing with Inflation

Many recent headlines have been emphasizing that the recent releases of PCE data suggest that inflation is still entrenched and that the Federal Reserve will need to increase interest rates further. The reason this is important is that higher interest rates reduce business activity, as it makes accessing capital (loans) much costlier. Furthermore, saving is preferred due to higher returns.

However, it is first worth noting, what has happened to inflation over the last year.

The chart above shows the CPI change year over year (i.e. over the last 12 months). Focusing on the first 3 months of 2023, the CPI rate is expected to be around 4.5%. So inflation has come down quite a bit from the 9% we saw last year, but is still above the long-run target of 2%. Why do we talk so much about this target and what is the Federal Reserve considering when making its decisions?

Sticky Inflation

The main concern with elevated inflation is the notion of inflation expectations – that is, what market participants believe inflation will be going forward. The theoretical reasoning as to why inflation expectations may matter for current inflation are based on a few assumptions stemming from what is called the New Keynesian Economics. The main assumption for New Keynesian Economics is that both wages and prices are ‘sticky’ – that is, they do not change quickly. Wages are sometimes assumed to be downward rigid, meaning that in nominal terms they do not go down (we rarely see firms reduce nominal wages for employees). Prices, on the other hand, do not change often because firms and producers find it costly. A typical explanation why firms may find it costly is the ‘menu cost’. The name ‘menu cost’ comes from restaurants. Restaurants, especially back in the 80s when this theory was first developed, would need to reprint their menus each time they would want to change their prices. This would entail an actual printing cost. Thus, even if the restaurant would want to change the price, the costs of printing the new menus did not make it worth their time. Only once their desired price changes significantly, would they alter prices.

Today, the printing of physical menus is less of an issue, but there are many other ‘menu’ costs, including the cost to: 1) decide on what price to charge for a good or service as is not a straightforward task and 2) maintain customer loyalty and attract new customers, as customers do not like price changes. Klenow and Kryvtsov (2008) finds that firms generally change prices every 4 to 7 months. Thus, when a firm decides to change prices, the firm must think about what will happen in the future, as they are unlikely to change prices for some time. This is where inflation expectations can start to make an impact. If a firm believes inflation will be high in the next 6 months (until they change their prices again), they will need to set a higher price right now to offset some of the future inflation. However, by setting the price higher today, inflation today goes up! This is the feedback loop stemming from inflation expectations. If we all believe inflation will be higher in the future, we will make decisions as if that is the case, making inflation high today. These expectations can also impact wage negotiations, which also happen infrequently – workers need to take into account future inflation when negotiating salary and wages.

It is worth noting that inflation expectations are simply a proxy for ‘‘future inflation’,1 which we cannot observe. Not all economists agree on whether inflation expectations (i.e. the specific number you and I think inflation will be tomorrow) actually impact current inflation (Rudd, 2021). However, inflation expectations might still correlate well with 'future inflation’, and many economists, including the Federal Reserve, typically use future inflation and inflation expectations interchangeably. Werning (2022) finds that inflation expectations impact current inflation between a 0.5:1 to a 1:1 ratio (i.e. a 1 percentage point change in inflation expectations changes current inflation between 0.5 to 1 percentage point). Furthermore, he finds that only short-run expectations (one year ahead) influence current inflation, rather than long-run expectations. All of this implies that if inflation expectations for the next year are high, inflation today will be high. Once inflation expectations decouple from the Federal Reserve targeted inflation of 2%, the Federal Reserve will find it difficult to bring down inflation to that level.

Clearly inflation expectations (or future inflation) matter a lot. That is why the Federal Reserve, in 2022, was determined to make sure everyone expects inflation to return to the 2% target soon and undertook an aggressive interest rate hiking policy, raising interest rates multiple times by 0.75% rather than the usual 0.25%. The issue for the Federal Reserve is that recent surveys suggest consumers believe inflation will be 5% in 2023, and 2.7% in the next 3 years. Based on the above theories, elevated inflation expectations may continue to be feeding through to current inflation measures. Furthermore, the recent PCE Core inflation figures came in higher than expected. PCE Core inflation, which is the preferred inflation measure of the Federal Reserve, is least volatile and most impacted by what may happen in the future.2 All this data suggests that inflation expectations are elevated.

Going Forward on Inflation

A lot of market commentators argue that only further interest rate hikes will bring down inflation. They believe that the other causes behind the inflation surge, especially supply chain issues caused by Covid and high energy costs, have gotten better recently and since inflation is still high, the only remaining driver of inflation is high wages. As I addressed a few weeks ago, wages are unlikely to be driving the current inflation spike, especially since real wages are still not growing (wages are up 6.1%, while CPI is at 6.4%). Furthermore, a recent paper by Lorenzoni and Werning (2023) argues that as long as any supply side issues (i.e. higher production costs) persist at all, inflation will remain elevated. Just the easing of supply side issues is not enough to bring down inflation to the 2% target.

Lorenzoni and Werning built a model that fits the current macroeconomic pattern of the US economy very well – an initial supply shock, such as Covid that closed factories, that led to price inflation and falling real wages. The ‘good’ news from their model is that, under certain assumptions, inflation will fall back to target (over 2 to 3 years) and real wages will see growth. The main mechanism driving their model is the tension between firms setting prices in order to earn a real profit (price above input costs) and workers targeting a real wage. As typically firms are quicker to respond to shocks (prices change more often than wages), once a supply shock hits that increases a firm’s costs, prices go up quickly. Workers respond to these increased prices, somewhat delayed, by demanding higher nominal wages. As these higher nominal wages reduce profits for firms, firms again choose to adjust prices. Since they’re able to adjust more often, prices grow faster than wages, leading to a real wage fall. Only after the initial supply side shock dissipates and the production costs for firms fall, can workers see real wage gains. This is because once the initial shock disappears, firms can still maintain the same profit level – they can pay higher wages, because their other costs are now lower. Once the shock dissipates, real wages and prices return to levels prior to the shock.

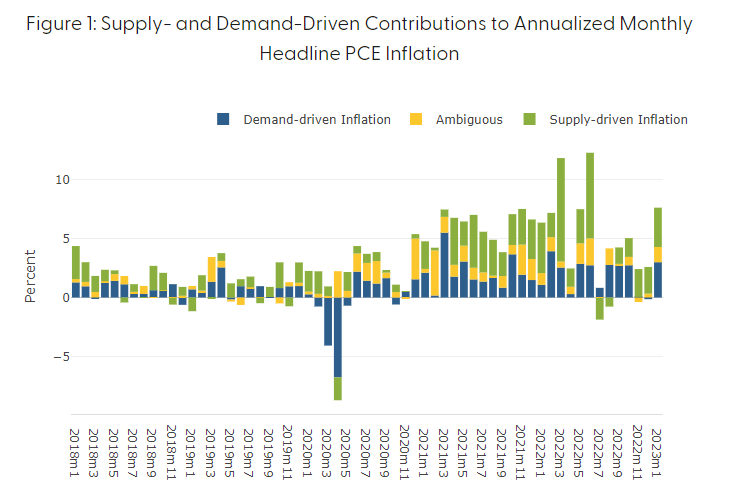

The main conclusion from this paper is that until the supply side shocks ease, inflation may remain elevated. Recent headlines suggest this is still the case: the world is still in a global chip shortage; equipment manufacturers report supply issues; even bakeries are struggling with getting raw materials. An analysis by the San Francisco Federal Reserve looked at separating some of the price changes due to supply issues (higher production costs) and demand issues (too much spending in the economy pushing up prices). The graph below suggests supply issues are still dominant.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve can bring down inflation by increasing interest rates significantly and reducing demand (higher interest rates induce people to save rather than spend). This would come at a cost to the economy – businesses would find it difficult to open and remain open, overall output would fall, unemployment would go up and a recession would occur. The issue for the Federal Reserve is that this increase in interest rates will also take time to impact inflation, due to sticky prices and inflation expectations. By that time, supply side issues might have fully eased, and the recession would not have been necessary to bring down inflation. That’s the decision the Federal Reserve is grappling with.

What I mean by ‘future’ inflation only makes sense in the context of looking at past data (we cannot see the future). Looking historically, if you want to determine why inflation in February 2022 was 7.9%, you can use ‘future’ data (i.e. what inflation was in January 2023) as an explanatory variable. In this instance, future inflation can explain why inflation in February 2022 was 7.9%. Since we cannot observe ‘future’ inflation currently, economists debate what exactly is future inflation and if it can be estimated. One of the main explanations is that future inflation is inflation expectations.

Since PCE Core strips away the volatile components from the measure, things like future inflation and inflation expectations influence it the most. The PCE Core is even expected to go above Core CPI, which is an extremely rare event (typically the CPI is higher as it puts a lot of weight on housing / shelter).