Correcting Economic Understanding: "Greedflation"

Greedflation, or profit-driven inflation, is being aggressively debated. Let's revisit economic theory.

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. Please consider supporting us and sharing this article in various social media!

If you would like to suggest a topic for us to cover, please leave it in the comment section.

Introduction

I wasn't planning on writing any new articles about the current high inflation period, but discussions on Twitter and Substack Notes suggest that there is a lot of misunderstanding (and unhelpful criticism) being thrown around.

Although I have briefly touched upon 'greedflation' in another article and several Twitter threads, as the issue is still attracting a lot of attention, a more in-depth discussion is warranted. Let's look at the state of debate and why instead of focusing on economic questions, many are pushing their own beliefs.

The Greedflation 'Scandal'

It is natural to assume that since firms want higher profits, they'll charge higher prices and this will generate inflation. Many have argued that the recent record profits of 2021 and 2022 demonstrate that, at least, some part of inflation is driven by profit margins. And they're right. Just not necessarily in the way they think it does. However, this idea started being discussed more heavily by the media, and also by quite a few central bank economists in 2023. More influentially, Prof. Isabella Weber has written a paper on this topic, arguing that some of the recent increase in inflation was caused by increased profits.

This paper and these views have caused many economists and economic commentators to argue vehemently that this is not the case. Many arguments of why inflation cannot have been caused by higher profit margins have been proposed. Some of the arguments mentioned include: 1) inflation is only related to the supply of money 2) data shows that profit margins have been decreasing 3) it's impossible for firms to get higher profit margins due to effective competition. Interestingly, proponents of these arguments might be right about profits not causing inflation – but again, not in the way they think they are.

So how can both camps be right (and wrong) at the same time? Let's get to the bottom of this.

Economic Theory

Nearly all central banks use a version of the New Keynesian model that we discussed previously in modeling the macroeconomic variables of the economy. The New Keynesian model directly links the rate of inflation with two components that impact pricing of a good: the level of real marginal cost of producing an additional unit of an item, and the level of desired (or target) firm mark-up. This latter component can be thought of as the desired profit margin of the firm.

If one subscribes to this model (and most central banks do), then right off the bat, we see that profit margins can impact the inflation rate permanently. Holding all else constant, if firms desire higher mark-ups (and are able to get them), the rate of inflation will be permanently higher. Anyone saying otherwise, must start off by declaring that the New Keynesian model used by central banks is wrong. This doesn't mean that this person is wrong, but it is helpful to establish what model or theory they think best explains the macroeconomic indicators we observe. Most commentary by economists and other pundits that criticize the ‘greedflation’ concept, simply ignore the existence of the New Keynesian model.

Is It ‘Greedflation'?

Although the previous section might make it sound like the cause of current elevated inflation could be 'greedflation', it, unfortunately, isn't as simple as that.

As stated by the theory, the inflation rate depends on the level of desired profit margin. Therefore, for the inflation rate to go up from the typical 2% we're accustomed to, the desired profit margin must have gone up. Did that happen?

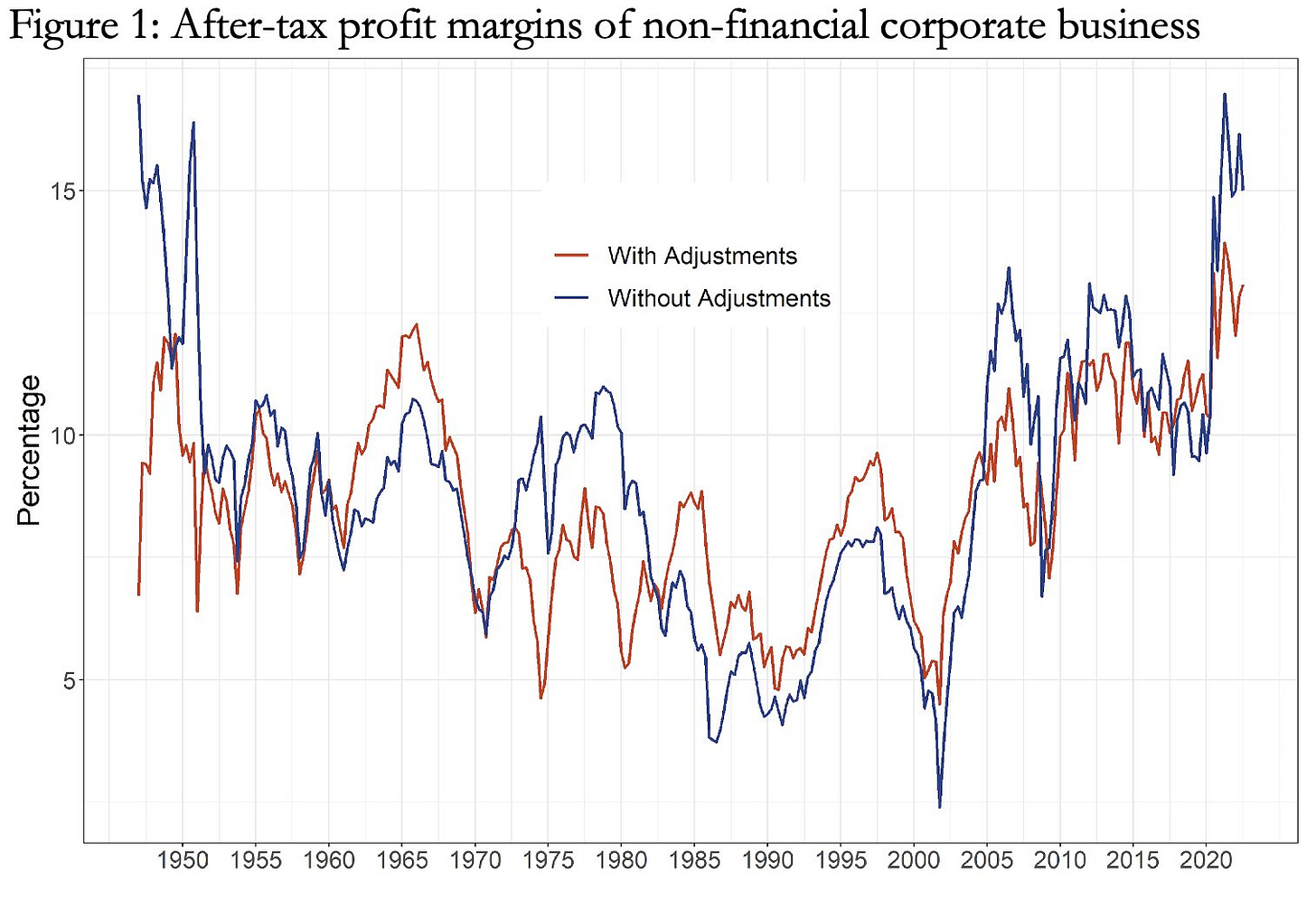

This is the key question that needs to be tackled. Unfortunately, it is much harder to answer than it seems. Many have looked at current profit margins and have found they have been higher than have occurred historically in the last 50 years.

Others are pointing out that profit margins have recently declined, while inflation has not abated.

The problem with the analyses shown above is that the data on profits we observe is not what we’re looking for. The profits discussed in both graphs above are realized profit margins – that is the actual profits firms made during the past 3 months. Desired profit margins, on the other hand, are the profit margins that the firm is targeting. In the New Keynesian model, firms only change prices occasionally – mimicking what happens in real life. Most prices are set and unchanged for a time period. This is due to the fact that there are costs associated with changing prices – such as the cost of physically changing labels or the cost of losing consumers since people don’t react well to constantly changing prices. For that reason, when firms set a price, they must anticipate what will happen with costs in the future and how consumers will react to the price. For this reason, the profit a firm actually experiences does not match the desired profit margin. Moreover, if firms miss their targeted profit, they’ll attempt to make up for it when setting prices in the future.

Therefore, looking at realized profit margins unfortunately does not help us to establish if desired profit margins went up (or down). Another recent approach done by certain economists was to look at sector specific inflation and sector specific profit margins. Their research showed that there isn’t any correlation between the two. However, not only are they again using realized profit margins instead of desired ones, but there is also nothing in economic theory that suggests that such a correlation (i.e. higher profit margins, whether realized or desired, in one sector would lead to higher inflation in the sector) should exist. The theory only talks about economy-wide profit margins and inflation!

Measuring Desired Profits

Unfortunately, the issue of measuring desired profits is currently a question without a specific answer. That is because we cannot observe it in any standardized way. Firms do not disclose desired profits officially. The best way would be to observe it from official macroeconomic data or from firm accounts. However, the only thing we can observe is the price the firms charge. But the price is a function of both the desired mark-up and the real marginal cost of production. One way to determine the desired mark-up would be to establish the real marginal cost. Unfortunately, this is also difficult. Real marginal cost is not average cost (total cost divided by number of units produced). It is the cost to produce an additional unit. These costs can be influenced via a variety of factors – needing to hire additional labor or pay overtime, or doing an additional shipment of materials. Even predicting whether the real marginal cost is higher or lower than the average cost is not straightforward.

When researchers, such as the ones mentioned above, try to estimate desired profit margins, they implicitly, without acknowledging, assume that the real marginal cost equals the average cost. Thus, they are actually calculating realized profit margins. If the real marginal cost is higher than average cost, then the computed realized profit margin (price - average cost) is higher than desired profit margins, since desired profit margin = price - real marginal cost. This skewing of results can lead to wildly incorrect interpretations of the data, simply because we’re not measuring the correct things. Moreover, the inflation rate can stay the same with rising desired profit margins. This can occur when real marginal costs fall, offsetting the increase in inflation rate due to higher desired profit margins. Simple analysis will not capture this fact. Additional research is needed to work on this topic and one day we may be able to determine how to calculate the desired mark-up.

What Can We Do?

Research on establishing the desired mark-up might take quite a while, so what can we do in the meantime? Even if desired mark-ups did go up, we would also need to establish why it went up right now. Saying they went up without any particular reason is not a satisfying answer. To establish a cause, we would need theoretical results that can be tested empirically.

Weber and Wasner (2023) proposed why desired mark-ups could have gone up. During times of supply chain bottlenecks, certain firms might all of a sudden gain oligopoly or monopoly power. In a market with less competition, firms can set prices to have higher profit margins. This is entirely expected behavior, well established by economists. For this reason, Weber and Wasner do not like the term ‘greedflation’, since if firms have gained monopoly or oligopoly power, even temporarily, they are acting exactly the same way any monopoly or oligopoly would behave. Interestingly, this paper has been the source of a lot of discussion and criticism from a theoretical perspective, although the theory behind it is very well established. However, it is unclear whether such (temporary) oligopolies or monopolies have in fact formed due to the Covid pandemic, resulting in recent higher desired mark-ups. This is a question worth conducting further research.

Conclusion

The debate around 'greedflation' quickly got derailed from a discussion of economic theory and empirics into a discussion of personal beliefs about what is causing inflation, rather than what the data and theory tells us. Economic theory clearly shows a connection between higher desired profit margins and a higher rate of inflation. Unfortunately, it is difficult to empirically establish the elements needed to determine if recent desired profit margins are higher. And we should be honest about this fact – currently there's no established way to determine either the desired mark-up or real marginal cost.

The focus of the debates and academic discussions should also be on what could have caused firms to increase desired mark-ups. This might also enable us to determine whether some of the recent inflation could be caused by higher profit margins, enabling us to enact policies to counter this (for example, pro-competitive policies and restrictions on mergers).

In this way, both critics and adherents of ‘greedflation’ are both wrong and right at the same time. Profit margins do drive the inflation rate and have always done so. But the question is did profit margins change – this is where ‘greedflation’ adherents do not have definitive evidence.

Lastly, even if it turns out that there was no 'greedflation', there is a lot of beneficial research that can come out focusing on this topic. Understanding more about a firm's mark-ups and real marginal cost would be extremely helpful for a variety of research questions. The recent highlighting of the hypothetical issue of 'greedflation' will encourage a lot of new economic research that will be very beneficial. A similar situation occurred with the release of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the 21st century. The book focused on measuring wealth and income inequality over a very long time frame. The reception of the book was very mixed – many found it very convincing, while others have criticized its empirical work. Regardless, it led to a big boom in inequality research with a strong focus on policy effects on both income and wealth inequality. This inequality research became very helpful in tackling a lot of economic issues, such as the impacts of monetary and trade policy. The debate around 'greedflation', if it remains focused on a discussion of theory and empirics, can potentially lead to another beneficial research boom.

Interesting Reads from the Week

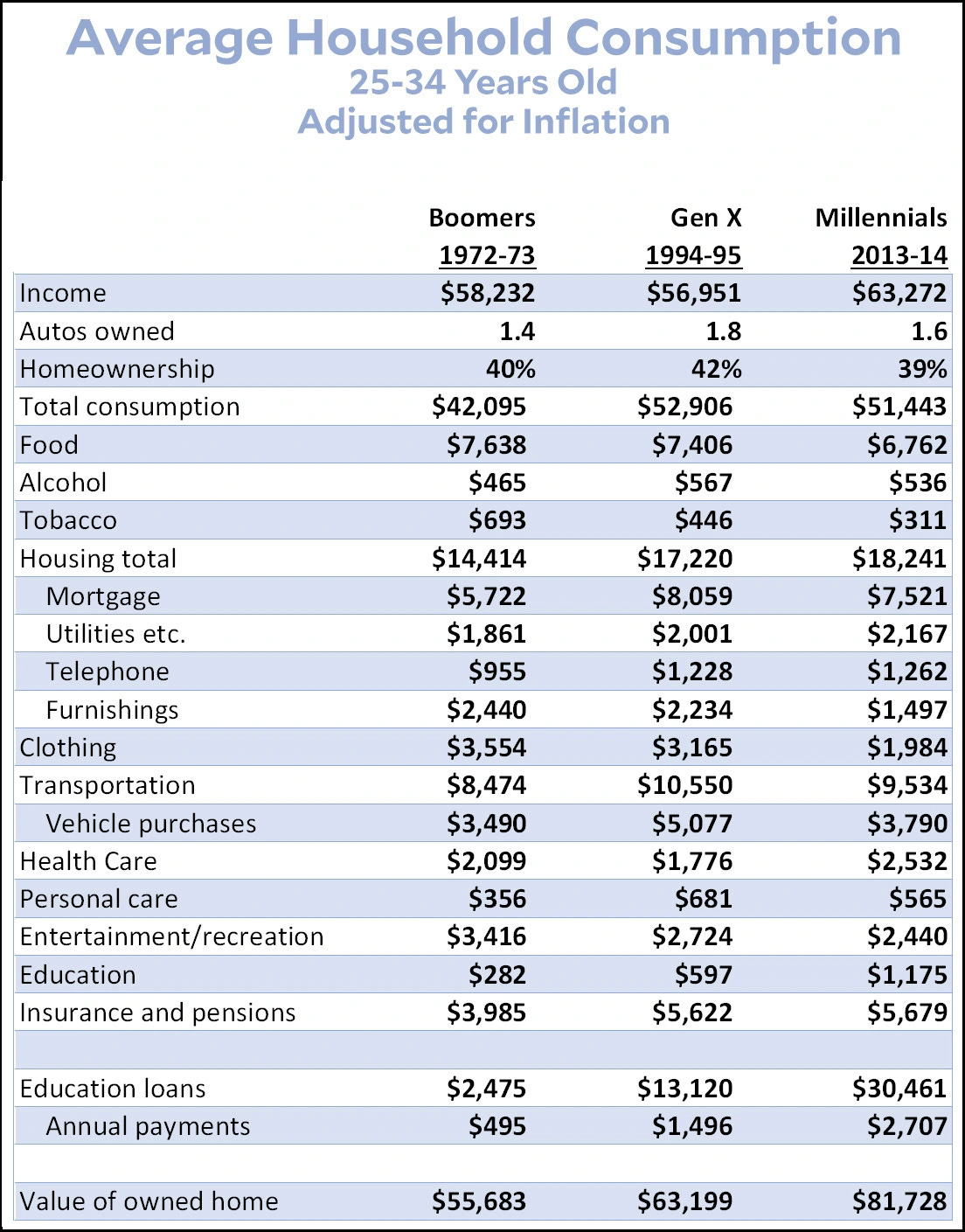

Article: How does income and spending differ between boomers, generation X, and millennials:

Tweet/Data: Currently, the mortgage debt service payments as percent of disposable income are still below pre-pandemic levels.

Tweet: Cancer mortality risk has been decreasing slowly over the years, suggesting this is due to slow and gradual research rather than any big breakthroughs.

Substack Note: An interesting take on CEO compensation, saying it should be linked to the performance of peer companies rather than to the stock price, as the stock price is influenced by many outside factors.

Tweet/Paper: A new paper on understanding uncertainty that we talked about last time. Here’s a little puzzle:

A $50 Amazon gift card is available. How much are you willing to pay for it?

A $50 Amazon gift card has a 10% chance of being available. If it is available, how much are you willing to pay for it?

Cover photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

(Un)intuitive Inflation (May 10, 2023) – what does economic theory tell us about how inflation is linked to the level of real marginal cost, and how supply chains issues, via real marginal cost, impact the inflation rate.

Wages and Inflation (December 4, 2022) – to what extent do wages cause inflation?

Government Debt - Should we worry about it? (January 23, 2023) – many are concerned that countries have very high government debt. Why we should focus on debt as a ‘tool’ for conducting inter-generational policy and what are sustainable levels of debt.

This is not on the right track IMO. The theory presented here doesn't help, because no "greed index" or desired profit margins increased. (As a producer/businessperson, I can tell you that desired profit margins are always infinite.) "Greedflation" is not a thing that anybody is claiming. *Achievable* profit margins increased. For whatever reasons.

Easiest understanding of that: firms (at least perceived that) they were facing steep demand curves: Price increases had limited impact on quantity sold, aka low elasticity of Q to P. Their pricing-related comments on earnings calls made that crystal clear. And it seems their perceptions were right

At the extreme: If the demand curve is vertical, increasing prices is printing *pure profit,* straight into owners' pockets. (Vs. boring revenue gains from >er Q. Yawn, so old-school.) Ka-ching. Who's not gonna do that?

Now: *why* the steep (perceived? actual?) demand curve? There's the question. Corporate concentration comes quickly to mind. If there's a limited choice of sellers and they're all raising prices... Where ya gonna go?

Thanks for listening.