Good Models – Good Ideas

To think about economics issues, it is helpful to use good models. But what makes a model ‘good’?

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. Please consider supporting us by liking or commenting on this post, as well as sharing this article in various social media!

Introduction

This article is a companion article to the article posted previously, which can be found here. In it, I briefly mentioned how by following a good model (Lorenzoni and Werning (2023)), I was able to gain valuable insights about the causes of US inflation, what would bring it down and what was the likely trajectory. In today’s post, I will discuss what is a good model, how to spot one and how not to fall for overly-simple ideas.

Importance of Models – What are they

One of the main reasons I started this Substack is because I believe that Economics has a lot of tools that can help us think through a variety of social issues. One such tool is models. A model is a simplification of reality that allows us to consider different eventualities, as well as determine causality. Whenever discussing any abstract question, it is always helpful to have a model in mind (or ask for the model the person is considering if you are debating an economic issue, such as inflation, with someone). Any model generally starts off with a set of assumptions and rules of the model. For example, nearly all macroeconomic models start off with the idea that an individual wants to maximize utility (i.e. their welfare, usually measured in how much an individual consumes). An example of a rule in such a model is that no individual can be forced to work or not work – they choose to work, because it allows them to consume.

These assumptions and rules of a model combine to form a mechanism – how completing one action feeds through the model, resulting in a specific outcome. For example, as discussed in our previous article, increasing interest rates lowers inflation by reducing wages and overall income. That’s the mechanism. Therefore, when discussing these abstract ideas, by having a model, we can specifically focus our discussion on what are the assumptions and rules we have in our model, and therefore what mechanisms occur. This results in a productive discussion, as we can talk about any disagreements regarding the assumptions or the rules, and how we can add data to our model.

What makes a good model

Not all models are created equal. Although many people often say that a simple model (one with fewer assumptions and rules) is the best, that may not often be the case. A good model, in my opinion, is one that: 1) has multiple potential mechanisms – for example, inflation can be reduced either via supply chain issues receding or interest rates being increased; and 2) the outcome of a mechanism is not a foregone conclusion – for example, under some circumstances, increasing interest rates might be very effective in reducing inflation, while in other circumstances, it might not be effective.

An example – Working-Out

Let’s go over an example of how we, sometimes unknowingly, build models and do not realize that they may be bad models.

Suppose you want to increase your upper-body strength. Assume you do not know anything about muscle development and proper training regimens. However, you do know how to do push-ups. And you’ve also seen strong people do a lot of push-ups. So you start doing push-ups, and you feel that your upper body strength is improving. Therefore, you (probably subconsciously) build a model of muscle growth, which assumes that when you do push-ups, your upper body strength increases.

You may even start your own training regimen, whereby you do 50 push-ups one day, 60 push-ups the next day, 70 push-ups the day after that, and so on. Everyday you do these push-ups, and you feel stronger. However, there will be a point, say two weeks into this regimen, that you will no longer have any additional increase in upper-body strength. You may tell yourself that the reason behind the slow down in upper body strength gains is that you’re not doing enough push-ups, and should do even more of them. Since push-ups increased my upper body strength previously, it’s logical that just doing more of them will continue to increase my arm strength, right?

Obviously, today, with all the knowledge we have (and have access to), we know that only doing more push-ups will not result in continued increases in upper body strength. We need to do other arm exercises, do exercises for other muscle groups, take multi-day breaks between exercises to allow our body to heal and grow muscle, and even change our diet. Our initial model, that stated “more push-ups = more upper body strength” was simply bad, even though it sounded logical and, in the very beginning of your training regimen, it did increase your upper body strength. This initial model only had one tool – push-ups – so that was the only thing we thought we could do. And the model might be correct to a degree – if you keep doing more push-ups, you might continue to increase your upper body strength, albeit at a very slow pace and potentially causing injury to a lot of joints.

Analogy

So how does this analogy compare to economics and inflation? If we want to model how to get to a healthy inflation rate of 2% (strong upper body), but the only tool we have is raising interest rates (doing push-ups), we might end up with an erroneous conclusion – that if we just raise interest rates aggressively enough, we will achieve 2% inflation. But in reality, we know that there are many other things that we should take into account. For example, things like allowing the supply shock to dissipate, waiting for the lagged impact of monetary policy or allowing government policy to play out (e.g. the end of the student loan interest payment pause). Moreover, what has caused inflation to rise in the first place could also alter how it should be dealt with. It is important to take these elements into account, just as a personal trainer will tailor your workout regimen, taking into account your current physical state.

Conclusion

The issue with modeling can be summarized with one of my favorite sayings – if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Models that only have one moving element will always show that moving this element does something. But just because it is simple, it does not mean it is right. Many highly publicized comments and ‘hot-takes’ on inflation are basically people with a hammer, usually managing to describe any economic development in a way to suit their narrative.

The danger with such models is that we may attribute the outcomes we observe to the tool in the model – just like we might erroneously think that someone with strong arms only did push-ups. With exercising, since it is a physically testable model, we can quickly find out what works and what doesn't. To keep the economy in balance, we don't have that opportunity, as there is no way to conduct a test whether we should have raised rates or not, waited for supply shocks to dissipate or acted quicker. For that, we need models as that is where we can conduct our tests. And these models need to be simple enough so that they can be used, but sufficiently complex to actually be of use. This is why the Lorenzoni and Werning model I saw before piqued my interest, as it satisfied these criteria.

In contrast, early on during the inflationary surge, many commenters did not provide their ‘models’, preferring to state more generic phrases such as ‘we need higher rates to curb inflation’. Without a model, their statements are not testable, and thus, they can always seem correct. Commenters and experts that do provide their models, even if their models or predictions turn out wrong, should be praised, as their actions contribute to a healthy and constructive discourse that can push our knowledge frontier.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Nick Timiraos of the Wall Street Journals talks about the importance of the causes of inflation and what brought it down, in light of what the Federal Reserve should continue. This is similar to my own thoughts on this topic.

Paper: A study looking into video-game play found that it has a small positive impact on well-being.

Paper: A working-paper that suggests that newer versions of ChatGPT are worse than previous versions.

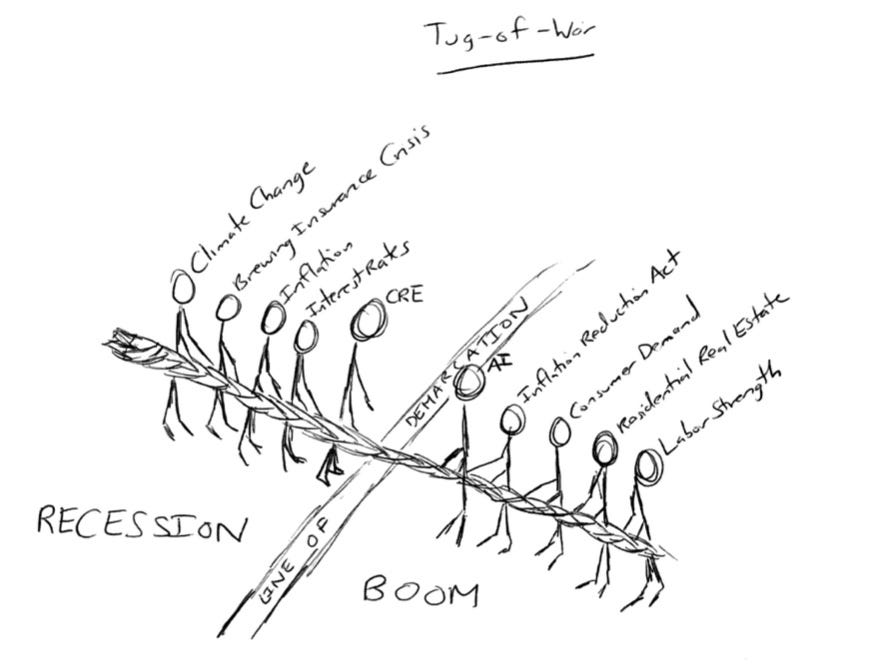

Article: Stephanie Losi discusses the two sides of the ‘will-there-be-a-recession’ debate and why there is so much talk about it.

Cover photo by Mosntera.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Causes of Current Inflation (December 18, 2022) – what was behind the inflationary surge during the Covid pandemic?

High Profile Layoffs (February 14, 2023) – how the recent layoffs in the tech sector will affect the wider economy.

Housing – Will deregulation fix everything? (April 9, 2023) – would removing zoning laws and housing regulations lead to an increase in housing supply and improve housing affordability.