Did The Federal Reserve Make a Mistake?

A higher unemployment reading has stoked recession fears and led many to think the Federal Reserve made a mistake.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

If you would like to support us further with reaching our 1,000 subscriber goal by year end, please consider sharing and liking this article!

During the week of July 29, swathes of economic data and decisions occurred in the US, which have led to many opinions that the recent decision by the Federal Reserve on July 31, 2024 to hold interest rates steady was a mistake. Let’s dive into what happened, and why, although I believe the Federal Reserve did make a mistake, it won’t be too consequential.

Brief Timeline

Below is a brief timeline of events:

July 31, 2024: The ADP (Automatic Data Processing – a company that provides payroll services to many US business covering 20% of the US workforce) employment report comes in below expectations – 122,000 new jobs created vs. 150,000 expected;

July 31, 2024: The Federal Reserve decides to keep interest rates fixed at 5.25%-5.50%;

August 1, 2024: Initial jobless claims (i.e. number of individuals filing for unemployment benefits for the first time over the previous week) came in at 249,000, which was above expectations of 235,000;

August 1, 2024: The ISM (Institute for Supply Management) Manufacturing index, is a survey of purchasing managers in the manufacturing industry that asks survey participants if certain activities, such as new orders, employment, production, are increasing, decreasing or stagnant in their companies. The responses are collated into an index, where a number above 50 suggests an increase in economic activity, a number below suggests a decrease. The number came in at an 8 month low of 46.8 against an expectation of 48.9;

August 2, 2024: The US employment reports for July was published with the number of new jobs below expectation – 114,000 vs. 185,000 expected; unemployment went up to 4.3% (vs. expected 4.1%)

The above economic data mostly came in below expectations. Moreover, this data came right after the Federal Reserve made its interest rate decision, which made many commenters and market participants fear that the US economy may fall into a recession. US stock markets fell by 5%-6% over the two days following the Federal Reserve meeting on July 31, 2024.1

Recessionary Fears and the Sahm Rule

One of the main reasons for the recessionary fears in the media was the triggering of the ‘Sahm Rule’. The Sahm Rule, developed by Economist Claudia Sahm (also a fellow Substack writer!) in 2019, tells us that if the average unemployment rate over the last 3 months is 0.5 percentage points higher than the lowest single-month unemployment reading over the last 12 months, then we are in a recession. The most recent Sahm Rule reading came in at 0.56.2

Recessions are often identified as recessions well after they have already started due to the lagged Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth information, which is only published every 3 months. Since recessions often require two quarters of negative GDP growth, this can mean a recession can be announced with a 6 to 9 month delay. Thus, the purpose of the Sahm Rule is to act as an early warning signal about the state of the economy and highlight that a recession may already be occurring. This information could then be used by both fiscal and monetary policy to respond earlier and mitigate the effects of a recession.

The rule has been shown historically to have been a good predictor of recessions – the Sahm Rule, tested on historical data, would have predicted all 11 recessions since 1950, with only two additional ‘false’ predictions.

Is the US in a Recession?

Given the current Sahm Rule trigger, it is natural to ask whether the US is in a recession. The answer is that most likely no. First, Claudia Sahm herself argues that this time around the Sahm Rule trigger is probably flashing a false positive. This is in part because of the uniqueness of the economic recovery since the COVID pandemic. Most of the rise in unemployment is not that people are being laid off, but rather that more people are entering the labor force and looking for work.3 Some of this is driven by an increase in immigration as well.

But most importantly, for now, all other economic variables suggest that the US is nowhere near a recession. The following chart by Economist Justin Wolfers shows the key US measures that are used to determine whether we are in a recession – all of them are growing:

And as of now, the Atlanta Federal Reserve GDP Forecast for the third quarter of 2024 is a real growth rate of 2.9%, which is suggesting significant economic growth.

Since we are most likely not in a recession, but we may be in a slow-down due to the increase in unemployment, why are there many comments suggesting the Federal Reserve made a mistake and should have cut interest rates?

The Federal Reserve – Did They Make a Mistake?

The question of whether the Federal Reserve has made a ‘mistake’ is a complex one. It requires looking back at the entire sequence of events since the COVID pandemic inflationary surge, some of which we have described in our previous articles. To analyze the Federal Reserve’s decisions, I broke down the last four years into three key time periods and decisions – the decision to increase interest rates in response to the inflationary shock, the decision of how high should the interest rates be, and the decision of when to cut the interest rates.

Supply Shock – Inflationary Surge

During the COVID pandemic, due to safety precautions, many businesses were often forced to temporarily shut down due to lockdowns or had to alter their production methods to satisfy social distancing and capacity requirements. This naturally increased the real cost of production – for example, what may have previously taken 10 hours to make would now take 12 hours to make. This increased real marginal cost is directly linked to an increase in the rate of inflation (which we have discussed in depth here).

The optimal policy by the Federal Reserve to address the supply shock-driven inflation surge, as discussed by Lorenzoni and Werning (2023), can be to run the economy ‘hot’ (i.e temporarily have the economy produce more than its long-run potential) while the supply issues resolve, which results in inflation to continue to be higher than target. At the same time, in a ‘hot’ economy there is greater labor demand as businesses keep expanding, which allows for workers’ wages to catch up.4 The ‘hot’ economy also helps resolve some supply issues, as it encourages more business to form, alleviating the supply issues.

My Opinion: Given inflation surged right after the pandemic, it appears that the Federal Reserve did run the economy ‘hot’. Whether this was a deliberate decision or not, from an optimal policy standpoint, this decision appears to be correct. The Federal Reserve, in my opinion, acted well.

Demand Shock – Stimulus

During the COVID pandemic, the US government enacted several fiscal policies such as stimulus checks, business wage support programs and the expansion of tax cuts. This also kept the economy running ‘hot’. These fiscal policies, funded by an increase in US government debt, also resulted in certain demand-driven inflation, which is when individuals have more money than the economy is able to produce. The amount of excess inflation caused by the ‘loose’ fiscal policy is not clear, but it is most likely far lower than the amount of supply-driven excess inflation.

To counter the demand-driven inflation, the Federal Reserve conducted multiple rounds of interest rate hikes, going from 0% interest rates to 5.25-5.50% interest rates. Higher interest rates increase the costs of opening businesses and running them, as a business would typically need loan financing for these activities. Lower business activity, means lower demand for employees, increasing unemployment and reducing the ability of workers to bargain for higher wages (with a larger amount of unemployed workers, a firm can be more frugal in the wages it offers a potential employee since it is easier for the firm to find another worker).

My Opinion: The decision by the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates was correct. Since there was demand driven inflation, which resulted in inflation being above the 2% target, hikes were needed to bring down the rate of inflation.

However, the question of how high did the interest rates need to go is more open. Theoretically, this shouldn’t be a big issue – if the interest rate is set too high or too low given data, the Federal Reserve could just change it accordingly. However, due to the nature of the Federal Reserve’s decision making process, it appears the Federal Reserve likes to see the interest rate move in a constant direction. That is, the Federal Reserve does not seem to want to increase rates in one month, then reduce it the next month, and then increase the rates again in the next month. The last time the Federal Reserve cut and hiked interest rates soon after was during the high inflation times of the 1970s and 1980s.

Given the preference by the Federal Reserve to change interest rates in one direction, the 5.25-5.50% interest rate may have been too high. The long-run interest rate will most likely be in the 3%-4% range (2% inflation + 1% productivity growth) as it would give a real return of approximately 1% to 2%, in line with productivity growth. Thus, had interest rate hikes stopped closer to 3-4%, we may have potentially avoided the recent significant increase in unemployment.

The Last 12 Months

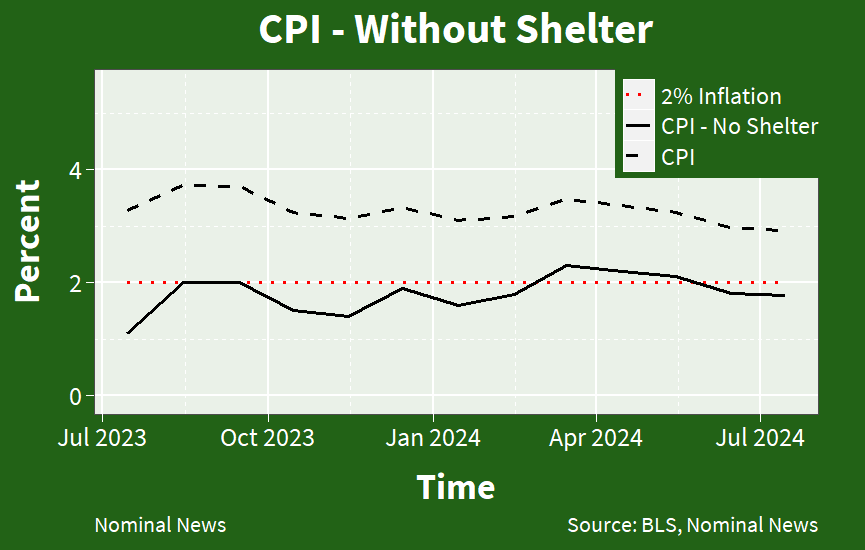

The Federal Reserve has kept interest rates unchanged over the last 12 months since August 2023. As we wrote in June 2023, inflation appeared to be under control. However, due to the unique way the US measures inflation – including hypothetical rents of people who own their homes called Owner’s Equivalent Rent (OER) – all of the inflation measures remained elevated.

This kept pressure on the Federal Reserve to keep interest rates elevated. Moreover, since the US economy was ticking along well – both GDP growth has been high and unemployment low – it was thought that there was no need for any interest rate cuts.

My Opinion: The problem with the above argument is that it ignores that the US economy is more akin to a large oil tanker ship – it changes direction slowly. The interest rate hikes have, unfortunately, finally resulted in increased unemployment, as predicted by standard economic research. Continued elevated interest rates will result in further unemployment increases. However, the impact of cutting interest rates right now would most likely be seen only in several quarters. Businesses have already made their investment and hiring decisions, and won’t speedily change to a modest interest rate cut. The economy, like an oil tanker, when it is slowing down, will take time to re-accelerate.

Many have argued that the Federal Reserve should have cut interest rates in July by 0.25 percentage points and that it was a mistake they did not. Personally, I do not think a 0.25 percentage point cut would meaningfully change the economic trajectory. The interest rate cut would have to be far larger (possibly in the 1 percentage point range) to motivate businesses to invest today and not wait till later. Moreover, had the Federal Reserve never raised rates past 4.25%-4.50%, we would already be at the lower interest rate and the discussion about cutting rates today would be moot.

Finally, although we can debate whether a mistake regarding interest rates was made, the size of the mistake also matters. Without a doubt, this economic slow-down and increase in unemployment has reduced wage growth, which is consequential to workers. Wage growth, in nominal terms, came in at an annualized rate of 3.6%. It is worth noting that US productivity grew by about 2.7% over the last 12 months, meaning that wages should be growing at 4.7% (2% inflation + 2.7% productivity).

At the same time, it appears extremely unlikely that the US will enter a recession in the near future. The economic slow-down does not appear to be that big (yet), with real wage growth still being substantial, and unemployment is still at historically low levels. Thus, the ‘mistake(s)’ by the Federal Reserve, whether increasing rates by too much or cutting too late, appear to be minor, fortunately.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article/Paper: Pascal Michaillat discusses his recent paper with Emmanuel Saez, where they propose a new real-time recession indicator, utilizing the Sahm Rule. Based on their current assessments, the US has a 40% probability of being in a recession right now (and thus, 60% that it isn’t).

Article: Natalie Wexler talks about research on the topic of school education. An interesting recent finding is that it appears that all children learn at the same rate.

Inflation data: It appears that people do not expect inflation to be elevated in the near future.

Inflation Data: Moreover, the Producer Price Index (PPI), which are the prices producers receive for selling their goods and services, came in below market expectations. Headline PPI came in at 0.1% on month-on-month basis. Over the last 12 months – 2.2%.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Monopolies and Antitrust Enforcement (November 20, 2023) – with news of the Federal Trade Commission suing Amazon for anti-competitive practices, economic research suggests that such lawsuits typically improve overall welfare.

Recession Talk (May 21, 2023) – news and social media are talking a lot about a recession, but the economy has been performing very well. However, it turns out that not everyone has been benefiting – and this time it was the high income individuals that saw real income declines.

Correcting Economic Understanding – Banning Ukrainian Imports (May 14, 2023) – several Eastern European countries banned imports of Ukrainian grain. Why this policy will have no impact on the grain price and the profits of farmers in the Eastern European countries.

One of the additional reasons for the drop in US stock markets may have been that Japan increased their interest rates from 0.10% to 0.25%. This resulted in many investors having to sell stocks to pay off loans they took out in Japanese Yen, in what is known as a carry-trade.

The three month rolling average unemployment is 4.09%, while the lowest unemployment rate over the last 12 months was in July 2023, at 3.53%.

It is worth noting that not all entry into the labor force is ‘good’ from a welfare perspective. If people must look for a job to make ends meet that would not be a ‘good’ outcome from a welfare perspective. On the other hand, if job pay increases significantly, then people may be tempted to re-join the labor force, which would be a ‘good’ reason.

Note that for running the economy ‘hot’, certain assumptions need to be met – wages are more ‘sticky’ than prices (i.e. wages do not adjust as much as prices, both downward and upwards), which seems like a reasonable assumption; and that, as a society, we care more about the real wage level than the price level. This last assumption is more subjective – in a society, workers will care more about their wages, but wealthy individuals might care more about price levels (their savings might be less valuable when prices go up).

"However, due to the nature of the Federal Reserve’s decision making process, it appears the Federal Reserve likes to see the interest rate move in a constant direction. That is, the Federal Reserve does not seem to want to increase rates in one month, then reduce it the next month, and then increase the rates again in the next month."

This is just an error in the Fed operating procedure. I suppose this arises from situation in which an unexpected event requires a "large" increase in the inflation rate and so a large increase in the interest rate instrument, but the Fed (for reasons that are not clear) prefers to spread the know amount of increase out over several decision points. In this process the change will be unidirectional. But his reasoning ought not apply to the process of disinflation (or any other situation) where the amount of change in the instrument is not known. Then a series of tentative moves -- down, pause, down or down pause up down -- as data arrives makes more sense.

https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/improving-fed-decisions

For historical reasons, I associate the "hot" injunction to be that the Fed change its objective function to accept more inflation for lower unemployment along a fixed Phillips Curve. I don't think that is what Nominal News or Lorenzoni and Werning have in mind. Rather, in the presence of sectoral shocks -- something important happens to affect supply (or demand) -- and when some prices are sticky downward, the Fed needs to allow/engineer inflation to temporarily rise above target and later engineer its return to target. I think it is better to say "above target inflation."