Inflation – The Story of 2023

The biggest economic story of 2023 was the fall in the inflation rate. Time to briefly revisit what has been happening.

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

If you would like to support us further, please consider sharing and liking this article!

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. If you would like to suggest a topic for us to cover, please leave it in the comment section.

When we last talked about inflation at Nominal News, it was in August, when we argued that inflation in the US will normalize in the following quarters The inflation data that has come in since August has confirmed this outcome – the rate of inflation over the last 6 months is back to its long run targeted rate of 2%. As inflation was the biggest economic story of the year, we found it befitting to discuss it going into the new year.

“Different” Inflation Measures

If we look at the most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI), the headline number we see in the news is 3.1%. Clearly this number is higher than the 2%, so how can we say that inflation has normalized?

Issues with Headline CPI

The reason is that headline CPI is not the best measure of where inflation is going to be in the future. The main purpose of measuring inflation is to inform the central bank where prices are heading, as maintaining a stable price level (commonly set as a 2% increase in prices per year) is one of the primary central bank goals (the other being full unemployment, which is uniquely an American central bank policy).

Moreover, since central banks only have a few tools, the central bank needs to know the prices (and therefore inflation) its tools will actually influence. For example, central bank tools cannot mitigate temporary shocks to energy prices or agricultural (food) prices. This is because the policy tools central banks have are more akin to navigating a large container ship which responds with a large lags to navigation commands. Changing interest rates, for example, only affects the economy over a long time rather than instantaneously, and thus it is impossible for central banks to dampen short-lived price shocks. By the time the impacts of a central bank policy are felt, the short-lived shock might be long gone, and central banks would have to revert their actions.

“Better” Inflation Measure (for Central Banks)

Thus, we need to focus on a measure of inflation that captures what the central banks can actually impact. One thing central banks usually do is omit items such as food and energy from the central banks’ inflation measures because both food and energy have very volatile prices. CPI without these items is referred to as Core CPI. But there are more necessary adjustments. CPI places a high weighting on housing expenditure. Housing expenditure is a somewhat controversial element of the inflation basket, due to the component of it known as Owners Equivalent Rent (OER), which alone accounts for almost 24% of the CPI measure (housing expenditure overall accounts for 32% of the CPI measure). OER is a measure of how much a homeowner would hypothetically be paying in rent. This homeowner is not actually paying this.

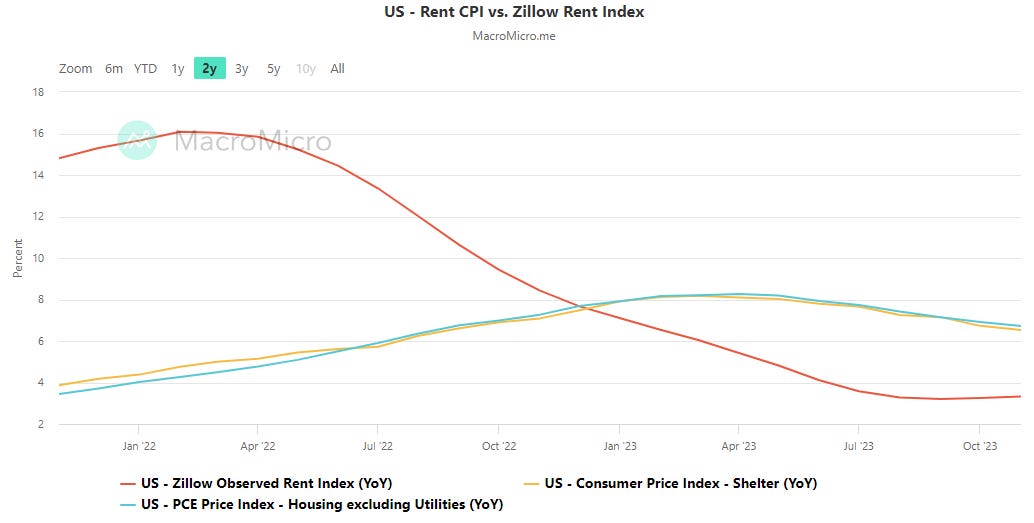

Moreover, the OER is known to be very lagged – that is, because of the way it is estimated, it does not respond to actual market rents immediately but over a period of time.

In the case of the current inflation discussion, OER within CPI (yellow and blue lines) remains very elevated, while actual market rents have declined (red Zillow based line)! This means that current rent inflation is definitely lower than what the CPI data tells us (it also means that rent inflation was higher than CPI rent inflation at the beginning of the inflationary surge, which can be seen in the graph).

Due to the fact that OER is a heavily estimated number, central banks like to focus on Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE), as the PCE measure puts less importance on housing. With that in mind the most recent headline PCE measure was 2.6% and the core PCE (i.e. PCE without food and energy) was 3.1%.

Time Frame

Reported inflation measures are also backward looking – that is, how much inflation has already occurred. What central banks (and everyone) care about is, however, what will inflation be going forward, not what it was.

This leads to using different time frames for any inflation measures. The most commonly used time frame for inflation reporting is year-on-year (i.e. the last 12 months). But this can capture a lot of past information. Focusing on a shorter time period such as 3 or 6 months can give us a better picture of where inflation is going in the next few months. However, focusing on too short of a time period, such as 1 month might capture too much randomness and one-off shocks. Thus some balance is needed and it might depend case by case. The recent 6 month core PCE measure came in at 1.9%, which is below the 2% target. Thus, if the next 6 months continue on a similar trajectory, by June of 2024, we should have 2% inflation on a year-on-year basis.

Taking all of the above into account, the Federal Reserve, in its recent meeting, basically stated that they do not expect to need to increase rates further to fight inflation.The Federal Reserve actually expects to start lowering the interest rate soon. How come?

My Thoughts

As we have discussed here at Nominal News in August, the inflationary surge in the US is over (even globally, inflation is cooling). The main cause of this inflationary surge appears to have been the supply chain bottlenecks that occurred during the pandemic. These bottlenecks increased real production costs (i.e. things took longer to make, and required both more staff at hand and paying of overtime wages, which are all real additional costs). Based on the New Keynesian model, this increase in real marginal costs (i.e. the cost to make one additional unit of a good) directly translated to a higher inflation rate.

With supply chains normalizing, the inflation rate fell. There is more disinflation from supply chains improvement still on the way. Core goods inflation (which includes items like clothes, cars and other commodities that are impacted by changes in supply chains) has now been at 0% since September. This will also translate into cheaper services, as almost every service uses some form of goods.

There are also no concerns regarding any future wage-driven inflation as the wage growth, which is currently at 4% over the past 12 months, is not too high. Wage growth of about 2.5% to 4% is considered to be sustainable in a 2% inflation world, as it equals inflation (2%) plus technological and productivity growth (between 0.5% to 1.5%). Moreover, after historically similar inflationary periods, wages typically grew at a higher rate than the 2.5-4% rate after the inflationary surge, making up some of the real wage losses experienced during the high inflation period. Thus, with the current wage growth of 4%, it appears there aren't any risks that could cause inflation to spike again.

High Rates – Dangers

The current interest rate of 5.25% is quite high by any standard in the US. The reason central banks raise interest rates to counter inflation is to slow down the economy. Higher interest rates do two things – encourage savings and make firm investment more costly.

Moreover, as firms find it now more expensive to operate, they scale back, which in turn lowers demand for labor, increasing unemployment and pushing wages down. With lower wages, people are unable to spend as much, putting downward pressure on prices. It is worth noting that this wage fall has not happened. Or at least not yet.

That's why the Federal Reserve needs to be ahead of the curve, as once a downturn starts, it might be difficult to stop (the container ship analogy). To prevent this downturn, the Federal Reserve, in its December meeting, showed that it is considering about 3 rate cuts in the next year. This sends a signal to firms that capital will be cheaper and therefore, they may consider conducting some of their investments now. With the higher interest rates and expectations of interest rates staying high, firms were holding off from making this decision. This decision from the Federal Reserve appears prudent and should help stabilize the economy at a 2% inflation rate.

Aside – Inflation Debate

Now that the inflation surge appears over, there is an active discussion on what caused the inflation surge and what brought it down. At Nominal News, we believe the data points strongly to supply issues being the primary driver of the inflation surge, and supply chain healing being the primary driver of the reversal. This is because of the mechanism described in the New Keynesian model which links the level of real marginal cost to the rate of inflation. This idea and model still puzzles many economists and commenters. The main confusion people have is the belief that improving supply chains (i.e. lower production costs) should lead to deflation (i.e. an overall price fall). That is not what the model predicts – returning to the same production costs as before in real terms will simply restore the previous rate of inflation. With this understanding, it appears most likely to me that the majority of the inflation shock was driven by supply issues (or more specifically, a shock to the real marginal cost of production) and the fall in the rate of inflation was driven by an improvement in supply chains.

Demand Story and Interest Rate Increases

The main arguments for the inflationary surge being driven by elevated demand (i.e. increased spending power of people) focus around the amount of fiscal stimulus conducted by the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic, estimated to be in the trillions. Now, I agree that some of the increase in the inflation rate was driven by this fiscal shock, but it most likely only accounted for a small share of the increase to the 9% inflation rate we witnessed.

If the inflation was demand-driven, we would need to have seen demand significantly subside in order for the inflation rate to fall. On the contrary, real individual consumption has been increasing. We also did not see falling wages or any significant increase in unemployment, expected results of decreased demand. However, inflation did drop back from 9% to 2%, implying the inflation was not demand-driven.

Moreover, the way central banks reduce demand is by increasing interest rates to such a level as to make capital very costly. However, the interest rates were never really high to have an impact (with inflation at 9%, any interest rate below 9% would still mean the real interest rate is negative – i.e. it is basically free to borrow money and capital is cheap).

Lastly, the rise and fall in the rate of inflation occurred in most countries around the same time as in the US and followed a similar pattern to the US. Each country during that time, however, had very different fiscal policies from the US. Most countries provided much less financial assistance to individuals to support consumption and demand, and yet these countries witnessed similar inflation developments. This again suggests that the inflationary surge in the US was not majorly demand-driven or that the recent fall in the rate of inflation was not driven by falling demand.

Inflation Expectations

Separately, the only channel that interest rates changes appear to have mattered are the inflation expectations channel – that is what we believe inflation will be in the future. The Federal Reserve, by raising interest rates and simply stating that they will bring down inflation, made market participants believe that inflation will be in the 2% range in the long run. These inflation expectations do feed back to the current inflation rate, but they would not be able to bring back inflation down from 9% on their own.

Summary

Overall, it appears the current evidence does not point to a predominantly demand-driven inflation surge, but rather a supply-driven inflation surge. Moreover, interest rate hikes also do not appear to have brought down the elevated inflation, but rather improving supply chains. The Federal Reserve, however, was right to increase interest rates to ensure inflation expectations remained anchored. Whether the Federal Reserve increased the rates too much or is being too slow in decreasing them, we are yet to see.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: New York Governor Hochul decided to veto a bill that would ban non-competes. Read here why non-competes are a terrible tool for everyone.

X/Tweet: A new paper discussing how firms with pricing power (i.e. large firms) are able to keep mark-ups/profits high during the supply chain disruptions.

X/Tweet: The debate around how much income inequality has changed in the US rests on several key assumptions – especially on who we think has unreported business income.

Cover photo by Karolina Grabowska.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Work Requirements (May 29, 2023) – work requirements are considered to be a helpful policy to incentivize people to work. Empirically, the data shows that this is not the case. It does not increase participation in the workforce and hurts the most vulnerable individuals.

Christmas Holidays and Gift Giving (December 25, 2022) – gift giving has been studied a lot. Typically, every year there are articles pointing out that gift giving is a net-negative action. What does economic research actually have to tells us about this, and why we should continue to give gifts.

Discrimination in Real Estate (September 17, 2023) – unlike explicit discrimination, statistical discrimination is less talked about. However, it has significant impacts on outcomes for people impacted by it. Real estate agents, often unaware of their own statistical discrimination, end up perpetuating outcomes for minorities.