Unions, Strike Action and the Economy

Union activity does not only influence unionized workers – it meaningfully impacts other workers too.

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

If you would like to support us further, please consider sharing and liking this article!

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. If you would like to suggest a topic for us to cover, please leave it in the comment section.

This year, 2023, we have seen an increase in the number of union strikes in the US. The most recent UAW strike has resulted in at least a 23% increase in wages for the strikers, along with other benefits. This level of strike action is generally not common in the US – with over 360,000 workers striking this year – a level not seen in over 40 years.

Most US workers do not belong to a union – only 10% of all US workers are unionized. Thus, it may seem like unions have little impact on the wider economy. That is not the case however. Today, we will discuss economic research that has shown some of the impacts of union activity on non-unionized workers, and how unionization rates alter wage inequality.

Economics Research and Unions

Before delving into today’s topic, it’s worth pointing out why the topic of unions is not extensively covered by current economic research. A union is an organization of workers that aims to improve their members' conditions of employment. Unions gain power by undertaking collective action – renegotiating work contracts, undertaking work stoppages. This enables them to have a stronger position when bargaining with their employer. By forming an organization, union workers gain monopsony power over their employer – i.e. they are the only supplier of labor to that employer.

Economists, on the other hand, study causality. That is, economists are interested in the question “how will X impact Y”. In the context of unions, framing this question is not easy. If we ask “how will forming a union impact workers”, we have a problem with defining which ‘workers’. Are we talking about how unions impact workers within a union or all workers in the economy? Even focusing on union workers might make little sense, since workers can switch jobs and no longer be part of the union.

Thus, economists typically focus on questions about ‘efficiency’ – how will unions impact efficiency. Efficiency is a mathematical concept that looks at how close the economy is to maximum output. Maximum output occurs when both capital and workers are allocated optimally – each worker works at the optimal firm to maximize overall, economy-wide output. From an efficiency perspective, unions are ‘inefficient’, as they can prevent optimal allocation of workers by keeping unionized workers employed at one particular firm, even if from a total output perspective, some of the workers should be at a different firm. Additionally, unions can push wages higher beyond their ‘efficient’ level, which can reduce employment and total output.

Efficiency, however, is not a ‘welfare’ measure. Welfare is a subjective concept, as it attempts to measure the well-being (commonly referred to as ‘utility’) people have. Welfare measures are naturally subjective since we cannot definitively establish how to convert income into happiness, not to mention the issue of whose welfare and happiness should we focus on (should we only focus on workers, all adults or even if we should focus only on citizens of a given country rather than the world).

Since welfare is subjective, studying unions and its overall welfare impacts is not currently a major focus of economics. On the other hand, economists have looked at more objective questions. We will look at two of them – how have unions impacted inequality (measured in income) and under what circumstances unionizing can get an optimal decision for workers.

Unions and Inequality

Income inequality has significantly grown in the US. The chart below from the Pew Research Center shows that since the 1980’s, the ratio of income at the 90th percentile (top 10% income earner) to income at the 10th percentile (bottom 10% income earner) has increased from 9.1 to 12.6 in 2018. That means that a person in the top 10% of income earns 12.6 times more than a person in the bottom 10% of the income distribution.

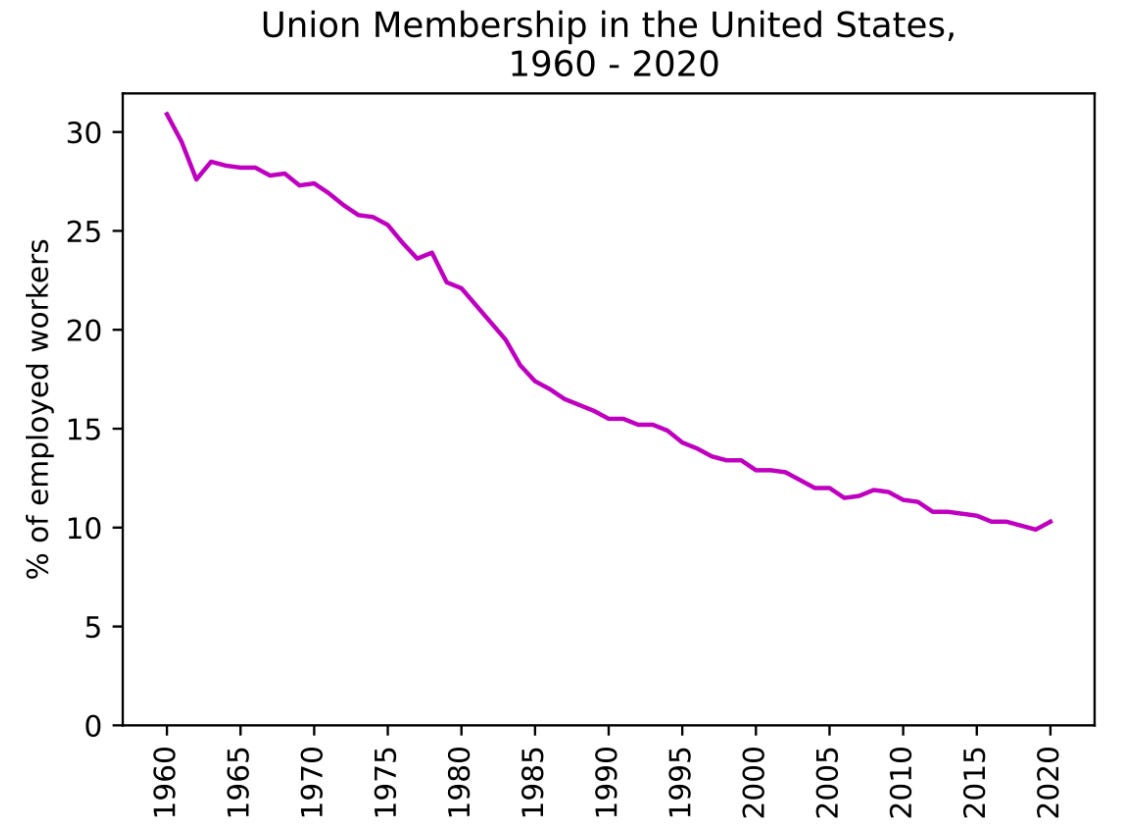

Beyond the magnitude of this ratio, what has concerned economists is the continued growth in this ratio. One contributor to the continued increasing inequality is the decline of unionization and union power. The unionization rate has been steadily falling in the US:

As we’ve shown in several other articles on Nominal News, comparing two graphs is insufficient to establish causality, as the relationship between these two data series – inequality and unionization rate – might be spurious.

Research by Fortin, Lemieux and Lloyd (2021) attempts to address the questions of how much of the increase in inequality can be attributed to changing unionization rate. The reason we are focusing on this paper is that, unlike previous research, Fortin, Lemieux and Lloyd have introduced a new crucial element to the analysis – the impact of unions not only on wages of a unionized worker ("union wages"), but also non-union wages. This is called a spill-over effect.

Thus, unions can impact wage inequality in three different ways:

Direct effect: the direct impact the wages of all union members via union negotiations with the employer;

Exclusionary effect: since unions might establish ‘inefficient’ wages (i.e. too high wages) – non-union members might not get a job at the employer and settle for a lower paying job at another employer;

Spill-over effect: the level of wages negotiated by unions, may be used by non-union workers as a comparable wage in their negotiations with their employer. Moreover, non-union employers, fearing that their workers may unionize, may offer higher wages themselves.

Including the spill-over effect is important, as without taking it into account, we could be underestimating the impact of unionization on reducing wage inequality. Fortin, Lemieux and Lloyd find that in the period between 1979 and 2017, falling unionization rates can explain 40% of the increase in inequality between the 90th and 50th income percentile, which went up from 1.8x to 2.5x. The spill-over effect accounts for half, or 20%, of this rise in inequality.

Interestingly, the spill-over effect was anecdotally demonstrated during the most recent US auto-manufacturing strikes. Immediately after the agreement between General Motors and the UAW union, Toyota, a non-unionized auto-manufacturer, raised wages for its employees, as media rumors appeared that UAW was considering organizing a union at the Toyota car manufacturing plant.

Who Unionizes?

In the prior section, we focused on how unions impact wages of others. However, this does not answer the question whether having unions is beneficial or not to individuals. As mentioned earlier, this is a difficult question to answer, but we can discuss what elements may impact the preference of individuals for forming and joining unions. Boeri and Burda (2008) present a good overview of what elements matter.

The main impact of unions is restricting wage changes, mostly downward wage changes. Theoretically, wages, which is a price for labor, can adjust just like any other price. If demand for labor goes up, wages go up. However, when demand for labor goes down, we rarely, in practice, see a wage reduction. Economists refer to this as ‘wage rigidities’.1 On the other hand, if wages did move up and down, we would be in what economists call a ‘flexible’ wage market, rather than ‘rigid’ wage market.

In a ‘flexible’ wage world, an individual’s wage would go up and down depending on overall market conditions and also on individual traits. Rigid wages prevent some of this wage change. In a union setting, wages could be rigid in both directions – they won’t go down, but even if an individual is more productive in a given year, their wage will not go up. Thus, what an individual thinks of their overall skill level and how the market is performing can impact whether they want ‘flexible’ wages or ‘rigid’ union wages.

‘Rigid’ wages, in effect, act as a risk redistribution mechanism between the firm and the employees. In a ‘flexible’ wage world, if an outside shock adversely or positively impacts production (for example, a jump in demand for a good or service), both the firm and worker will reap the benefit or the loss stemming from this shock. In a ‘rigid’, unionized setting, the shock’s benefits and costs are fully absorbed by the firm, as the worker’s wages are fixed. Therefore, whether an individual of a certain ability prefers ‘rigid’ wages depends on whether they want to share in the risk with the firm, or prefer a 'certain' wage.

Another important factor on preferring ‘flexible’ vs ‘rigid’ wages is the overall characteristics of the labor market. If it is easy to find a job, in case a worker is laid off, the worker may prefer ‘flexible’ wages, as unemployment is not that harmful for the worker.

On the other hand, if there is a ‘firing tax’ (a cost for the firm to lay off people such as legal and bureaucratic costs, separate from severance costs), workers may prefer 'rigid' wages. In a market downturn, under ‘flexible’ wages, firms would simply lower wages, while under ‘rigid’ wages, they would lay off workers. With a ‘firing tax’, however, it is costly to lay off. Thus, under a ‘rigid’ wage setting, firms would wait for the market to turn around and endure certain losses as it may be less costly than paying the cost of laying off workers.

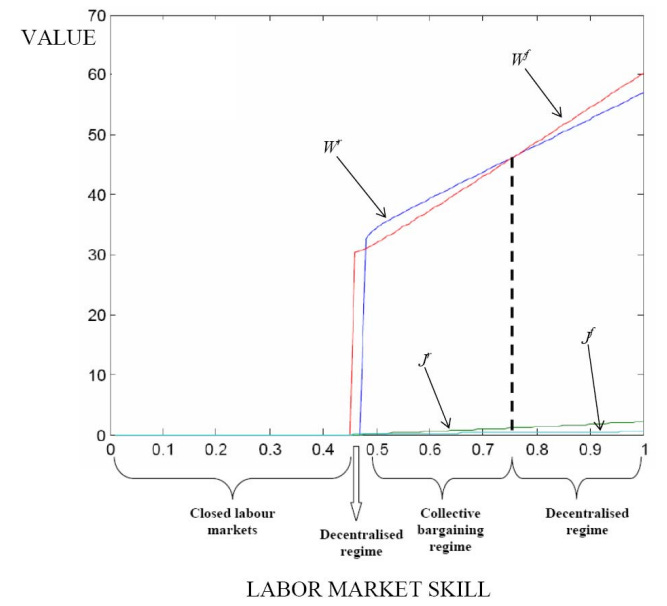

In attempting to determine who may want to unionize, Boeri and Burda took into account all of the above modeling assumptions and considerations and summarized them in the following theoretical graph:

The x-axis is a measure of skill level of an employee (based on the International Adult Literacy Survey). The y-axis represents the value each worker receives. The blue line is the value a worker gets from receiving a union wage, while the red line is the value they get from a ‘flexible’ wage. The lowest skilled individuals (up to about 0.44-0.46) are not employed in both union wage and flexible wage models, as they are not productive enough for a firm to hire them. Out of workers that are employed (skill level above 0.44-0.46) – only workers in the middle of the distribution prefer unionized wages (blue line above red), while lower skilled workers and highest skill workers prefer the ‘flexible’ wage regime (red line above blue).

The highest skilled workers prefer ‘flexible’ wages, because they have a lot to gain from sharing the performance risk with the firm. We can think of these individuals as CEOs whose performance is often dependent on external market factors. The lower skilled workers that are employed also choose the ‘flexible’ wages, because under unionized wages, firms would simply not hire them. By paying the union wage, a firm, in expectation, would make a loss on hiring this individual. Thus, these workers prefer to also share the risk with a firm, because they will at least be employed. The middle skilled workers prefer to forego risk sharing with the firm, and prefer 'certain' wages and lower likelihood of being laid off.

Interestingly, Boeri and Burda modeled Italy and Sweden using the above framework and found that in both these countries, a median individual would prefer to be in a union than not. Moreover, when looking only at the working population, approximately 85% of workers in Italy and 90% of workers in Sweden would prefer to be under a union. However, this analysis is a predominantly theoretical exercise rather than a full model that incorporates elements (other factors that may impact firm and individual decisions such as skill development or new business formation) that would be needed to determine the optimal unionization rate. Thus, the specific numerical conclusions by Boeri and Burda are not definitive.

Conclusion

Unions are a more complex concept from an economic standpoint than may seem at first. The impacts of unions go beyond just the workers in the union and the employer. Even under low unionization rates, union wage negotiations can actually impact wages of non-union workers. Furthermore, being in a union might actually be preferable for a majority of workers.

In the discussion today, we focused predominantly on the effects of unions on workers. We did not discuss the wider impacts of the union on the entire economy such as the impact of union on unemployment effects or on firm innovation levels. In these instances, unions may have adverse impacts on the economy, and thus, from an overall economic perspective, unionization may have ambiguous impacts. However, unions are important to analyze, as their impacts are quite large.

Interesting Reads from the Week

News: The October inflation data came in below expectations with CPI at 0% and Core CPI at 0.2%. Why we continue believe the inflationary surge is over.

News: More auto-manufacturers are increasing their wages in response to the strike action of UAW. This time, it is Hyundai.

Tweet/X: Spending on road infrastructure annually is quite high in the US – at $250 billion dollars a year.

Photo by Pixabay.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Industrial Policy – An Unspoken Issue (August 31, 2023) – many countries are turning towards industrial policy. But few discuss the issue of what will happen to workers once the subsidies to the manufacturing sector end.

Recession Talk (May 21, 2023) – news and social media are talking a lot about a recession, but the economy has been performing very well. However, it turns out that not everyone has been benefiting – and this time it was the high income individuals that saw real income declines.

Good Models - Good Ideas (July 30, 2023) – to think through the consequences of economic policies, it it important to have a model. However, for a model to be good, it needs to have enough flexibility to allow for a variety of, and sometimes opposite, outcomes.

Wages are typically nominally rigid. However, in real terms (i.e. after taking into account inflation), wages do fall.

Interesting article. I recently read a study on teachers’ unions. It found that when union power was reduced in the public school system, student attainment generally went up. It also found evidence that teachers unions tended to overpromise and strain budgets by spending down reserves more quickly and then seeking tax hikes to pay for them.

This is, of course, perhaps a difference between unions in the public and private sectors. I will be incorporating these findings into an upcoming essay.