Yes – Tariffs Have Increased Prices and Inflation in the US

The price increases from tariffs can be seen in both economy-wide data and retail data.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

If you would like to support us further with reaching our subscriber goal, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

Nominal News Highlight – New York City 2025 Elections

New York City local government elections are happening in 2025. Since I live in New York City, I’ve put together a post listing the Nominal News articles on the election isuses that are currently being discussed.

Recent US inflation data for the month of April came in low at 0.1% (2.1% over the last 12 months). However, after the US tariffs announcement at the beginning of April, economists had warned that inflation in the US will be higher. Given the inflation data came in ‘low’, some have argued that this demonstrates that tariffs do not push inflation up. This interpretation is incorrect. A more in-depth look by economists shows us how the tariffs have already increased prices of both imported goods and domestic goods.

Direct Retail Data

Data

Cavallo, Llamas and Vazquez (2025) (“CLV”) looked at the impact of US tariffs directly on store retail prices. PriceStats, a private data firm, collects daily prices of goods by scraping online price information of large US retailers. CLV focused their analysis on 4 large US retailers and collected price data on specific products.

Next, CLV matched the products in their data set to the country of origin of the product. Of the 4 retailers, 2 retailers listed the country of origin of their product on their website. This allowed CLV to determine the country of origin for around 300,000 products. For the remaining 2 retailers, CLV relied on a generative AI prediction model that would search online to determine the country of origin of the product. CLV found that this procedure correctly predicted whether a good is “Domestic” or “Imported” 88% of the time, and can predict the specific country correctly 85% of the time. The prediction method was still only applied to 10% of the sample, resulting in a total of around 330,000 products for which both prices and the country of origin information are available.

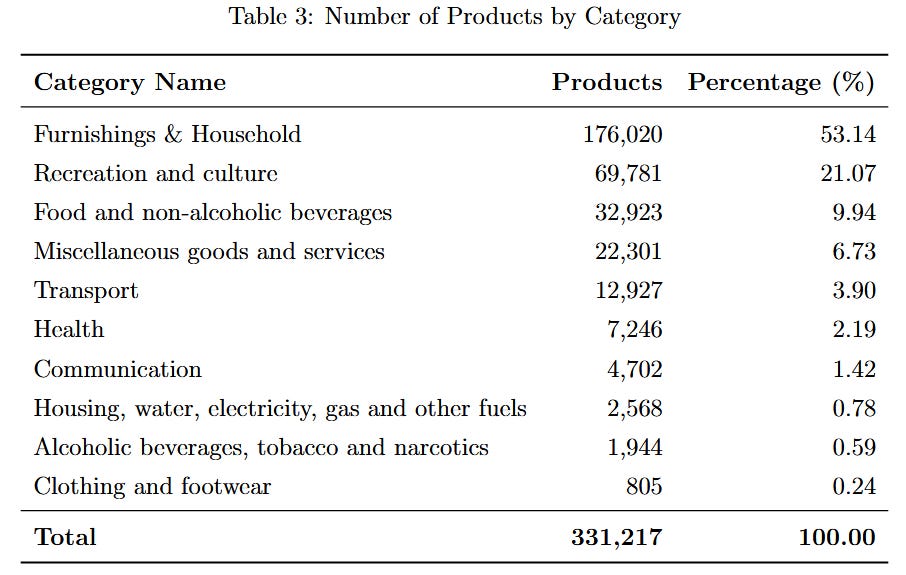

The scope of products covered is shown in the table below:

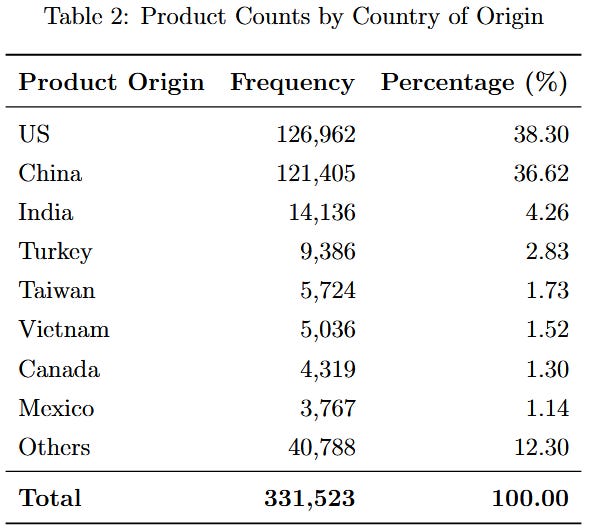

And here’s the distribution of goods by country origin:

Price Index Creation

To look at how tariffs impacted prices, CLV created various goods price indices by grouping goods based on the observables. Looking at single products would not be a good approach as there can be many reasons why the price of an individual product changes. Thus, it makes sense to look at products in a more aggregated way.

With the data, CLV are able to create price indices by country of origin, domestic vs imported goods, or type of good (any aggregation of goods is theoretically possible).

The way each price index is created is by looking at the relative daily price change of each good and then taking an average of these price changes over all the goods. The index itself is initialized at a date and set to 1 for the first date.

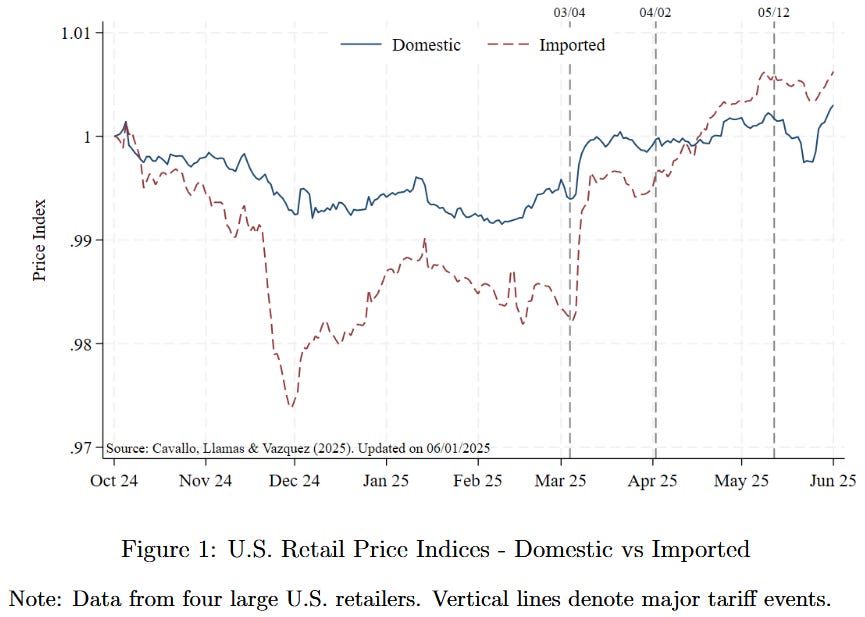

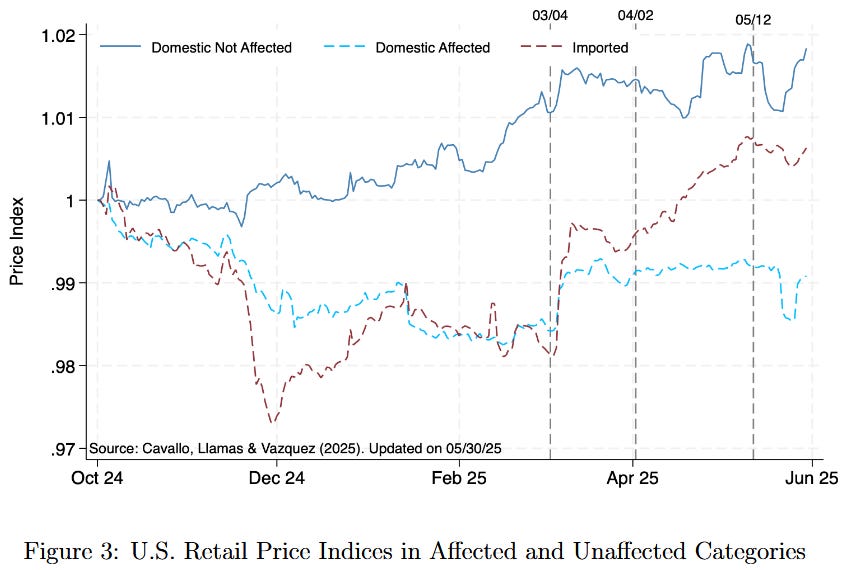

The chart above shows how prices of imported and domestic produced goods have changed since October 2024. The fall in prices through the holiday period is an expected seasonal pattern (the data itself is not adjusted for seasonality). A price jump occurred on March 4, 2025, when the US imposed 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and increased tariffs on China from 10% to 20%. Imported goods prices jumped up by 1.2 percentage points, while domestic goods prices jumped by about 0.6 percentage points.

The next key date was April 2, 2025, when the US announced tariffs on all countries. This led to a steady and continued rise in imported goods prices. The rise stopped on May 12, 2025, when the US announced a tariff reprieve. Since March, imported goods prices jumped up by 2.5 percentage points.

The announced tariffs were generally very large (tariffs on Chinese goods were anywhere from 20% to 125%) and although we do see a price increase, one might wonder why it is so low. CLV, who also looked at the 2017/18 tariffs, found that companies undertook several adjustments to deal with the tariffs including inventory front-loading (bringing in inventory before tariffs) and trade diversion (shipping via low tariff countries). Moreover, due to uncertainty of tariff policy, firms might also be hesitant in passing through the entire cost – if the tariffs are removed soon after the announcement of tariffs, the jumps in prices may deter customers (Rotemberg, 2005).

Country of Origin Differences

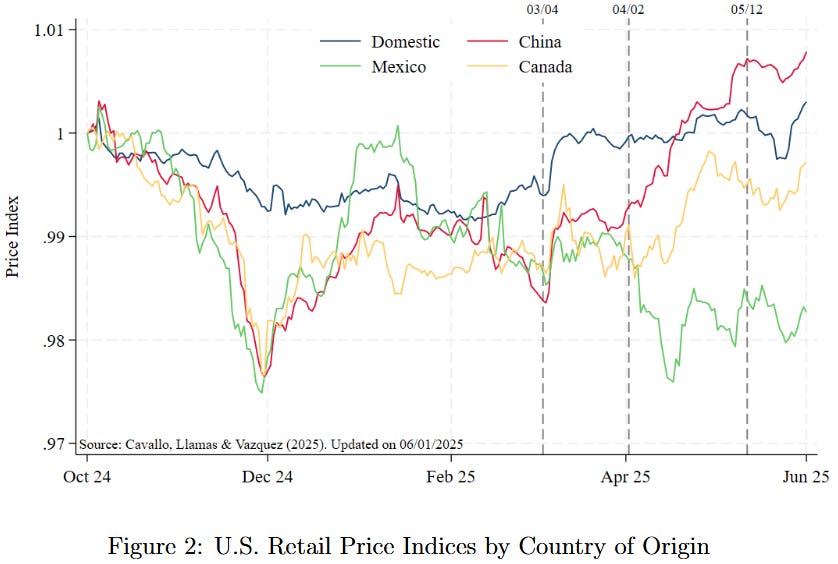

CLV also looked at the price index by country of origin:

What can be seen above is that after March 4, Chinese, Canadian and Mexican goods saw increases in prices. Mexican goods saw a fall in prices after April 2. Why? That is because most of the goods from Mexico fall under the USMCA trade agreement meaning the tariffs did not apply. This pattern actually adds validity to the method CLV used, as it seems reasonable that prices of Mexican imports would fall back.

‘Buy US Goods’

A common argument is that tariffs won’t impact consumers if they simply purchase domestic made goods. This is a false statement, because imports impact domestic prices:

directly, if the imports are intermediate inputs, or

indirectly, since workers will demand higher wages to purchase the higher priced imported goods.

CLV already found evidence of this in the data:

Domestic affected goods are goods that have components that were directly affected by tariffs. Affected goods jumped in prices immediately after the tariff announcement. The pause in price increases could be due to the points mentioned previously – inventory front-loading, trade diversion, as well as certain goods being exempted via trade agreements.

The rise in not affected goods suggests that tariffs do indirectly influence these prices. The exact mechanism is not clear but it could be driven by policy uncertainty (maybe the not affected goods will also face input tariffs) or firms wanting to maintaining relative price structures (i.e. if an import price goes up, the price of the not affected should increase similarly so that the difference is relatively the same).

Macroeconomic Price Increases

Above we saw how tariffs have translated into direct price increases by retailers. Economists are also interested in how prices are impacted more broadly, measured as price inflation. Minton and Somale (2025) (“MS”) studied the pass-through of tariffs on the Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index (PCE), the inflation measure used by the Federal Reserve.

Tariffs increase the cost of a good. A firm can choose to pass this cost in its entirety to the customer (this is called full pass through) or partially, by increasing the price. Moreover, since firms also want to make profits, how they determine their profit margin is also important. Firms can either make a constant dollar profit (e.g. a firm makes $2 per item sold) or it can make a percentage of cost profit (e.g. a firm marks up a good by 10% – the higher the cost, the larger the profit in dollar terms).

For their analysis, MS assumed that firms set target profit in constant dollar terms, rather than percentages. Then, MS looked at how much of the tariff was actually passed through by looking at how components of the PCE changed. First, MS looked at historic changes in PCE category prices between 2000-2017. Then they compared it to how these PCE category prices changed after tariffs. MS studied two tariff periods – the 2018/19 tariffs and the recent 2025 tariffs.

2018/19 Tariffs

MS found that for the 2018/19 tariffs, the tariff pass-through was actually two times larger – i.e. double the cost was passed through! It is worth quickly noting that the estimate is not precise and that the range of pass-through is between 60% of the cost all the way to 360% of the cost. Moreover, MS found that the pass-through of the cost was very quick – two months after the tariffs were enacted, the price of the goods jumped.

The fact that the pass-through estimate is above 1 (i.e. more than the cost was passed on to consumers) puzzled the authors a bit. MS suggest that the reason for this high estimate could be that during this time period (2016-2019), price changes were generally infrequent and thus firms, under the guise of tariffs, could increase prices by more than just the cost.

February-March 2025 Tariffs

MS also studied the most recent tariff changes. First, MS document that non-tariffed goods have been experiencing inflation below what was observed on average between 2000-2019. For the tariff impacted sectors, the pass through so far appears to be about 50% of the cost (the range is from 10% to 90% of the cost). The tariff pass-through thus appears to be lower than in 2018/19.

However, even this pass-through is meaningful. From January to March 2025, tariffs may have contributed around 0.33 percentage points to core goods inflation. Had there not been tariffs, the core goods inflation would have been -0.18% (deflation) rather than the observed 0.15% inflation. It is worth noting that prior to January 2025, a negative inflation reading for core goods was quite common in 2024. Overall, Core PCE increased around 0.5%, while absent tariffs, it would have been 0.4%.1

It is worth adding that it's only been a few months of tariffs and the policy changes have been very volatile, making price pass through decisions complicated for firms.

Tariffs, Inflation and Output

The above empirical studies confirm what theory has predicted – tariffs, when enacted, do increase inflation (assuming the central bank does not respond). It is worth noting that the theoretical long run predicted impact of tariffs is 0.5 percentage point higher inflation (up to 0.8 if other countries retaliate). Thus, we shouldn't see very large inflation jumps (like we saw during the Covid pandemic). The bigger impact will be on overall economic activity with GDP reduction between 0.8% to 1.6% and a real wage reduction between 2.7% to 4.5% (see our article here for supporting research).

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Joseph Politano breaks down how US trade has changed since the enactment of tariffs.

Article: Deeponomics looks at decision making and what economics tells us about the biases we have when making decisions.

Article: Tommy Blanchard talks about the research of how people perceive time, and whether time actually goes by faster as we get older.

To understand the magnitude of this increase, the Federal Reserve targets a 2% PCE for the entire year. Thus, in two months, tariffs on their own have already accounted for 5% (0.1% increase out of 2% target) of annual target inflation.

That is undoubtedly correct; but only because the consumer elects to pay up. Where the consumer does not have much of a choice is with too many basic food products, generic medications, and parts and materials required to repair most every car and electronic gizmos ever sold in America in the last few decades. The rest is pretty much discretionary. If I'm wrong; where?