Do Tariffs Cause Inflation? Yes.

No, it is not a one off jump – tariffs on intermediate goods result in permanently higher inflation (all else constant).

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

Our updated goal for 2025 is to hit 10,000 subscribers:

If you would like to support us further with reaching our subscriber goal, please consider sharing and liking this article!

Tariffs have taken over many economic and business discussions. One common topic being discussed is how tariffs impact inflation. Recently, there have been many opinions discussing tariffs and inflation, often arguing that tariffs are not inflationary. Let’s get to the bottom of this, using the latest research.

The ‘Tariff-Inflation’ Argument

Inflation is a rate of change measure. In simple terms, inflation is how much prices for goods and services go up over time (for a more in-depth discussion, please see our inflation primer).

Tariffs, on the other hand, are a tax on imports – an importing firm has to pay a fee for the imported item.

The reason many argue that tariffs do not cause inflation is that tariffs would only result in a one-time price increase. So it would be a large, one-off inflation jump, but prices won’t keep growing. Although it sounds reasonable, this view is only correct in a narrow sense – in almost all cases, tariffs do permanently increase inflation (under realistic central bank policy assumptions).1

Empirical Evidence

Cuba-Borda, Queralto, Reyes-Heroles and Scaramucci (2025) (“CQRS”) recently released a timely paper looking at the impact of trade costs on inflation, from both a data and model-based perspective.

Trade Costs

Trade between countries is not ‘cheap’. There are many costs involved in trade. Anderson and Wincoop (2004) partition trade costs into three buckets:

Transportation costs: the physical cost of transport + transportation time;

Border-related trade barriers: policy barriers (tariffs) + currency costs + language barriers + information cost (not knowing the market) + security barrier;

Retail and wholesale costs: the costs related to distributing the goods after they are imported.2

If you were to guess – what is the trade cost for a rich country such as the US in terms of the production cost? To clarify, suppose an item costs $10 to make at a factory abroad, how much does it cost to bring it to the US?

The answer may come as a surprise – Anderson and Wincoop estimated the cost in 2004 to be around 170% of the production cost. In the $10 example, that means the trade cost is $17, giving a total product price of $27. To give a break down of the costs, Anderson and Wincoop estimated the costs to be (as a percent of the production cost):

Transportation costs: 21%

Transport – 12%

Time Value – 9%

Border Related Trade Barriers: 44%

Policy/Tariffs – 8%

Language Barrier – 7%

Currency Barrier – 14%

Information Barrier – 6%

Security Barrier – 3%

Retail and Wholesale Cost: 55%

Note – these costs are multiplicative. To get the 170% cost, we multiply 1.21 x 1.44 x 1.55 = 2.7.

CQRS Trade Costs

CQRS re-estimated these trade costs for a much larger set of countries and over a wider period of time. This estimation of trade costs is not straightforward – there is no easy price list that can tell us how much each policy barrier costs. Thus, economists have to infer these costs from the observed amount of trade between countries. I leave the explanation of this process to the appendix.

Using a sample of 40 countries, CQRS estimated that in 1995, the median bilateral (i.e. between two countries) trade cost for final goods (e.g. cars, appliances) was 380%, while for intermediate goods (e.g. steel), it was 420%. By 2008, these trade costs fell by around 70-80 percentage points, to 310% and 350% for final and intermediate goods, respectively. Between 2008 and 2020, there hasn’t been any significant reduction in trade costs. Visually:

The blue (red) line represents the evolution of the median of the final (intermediate) good trade cost. The blue shaded area represents the 20th to 80th percentile of all final good trade costs (for intermediate goods it is the dashed red lines).

There’s also significant differences between which countries have high trade costs. Below is the plot of country pair specific trade costs:

The bottom black line represents the trade costs between the US and China for final goods. Interestingly, and partially confirming the validity of the estimation done by CQRS, the trade costs between the US and China went up in 2018-2019 by about 11 percentage points in final goods and can be seen in the graph above. For intermediate goods, the jump in trade costs was 20 percentage points. This matches well with the fact that the US imposed tariffs on China in 2018 were estimated to increase costs by 16 percentage points.

The remaining lines show various group country pairs. For example, the yellow AE line shows the median trade cost between advanced economies, while the top green line shows the median trade cost between emerging economies.

Trade Costs and Inflation

Using the above trade costs, CQRS plotted trade costs against the rate of inflation. Since trade costs may impact inflation over a longer time horizon, CQRS used the average inflation rate for the following 4 years. To elaborate, CQRS plot a country’s 2000 trade cost against the average inflation growth from 2000 to 2004.

Visually, we can see a positive correlation between trade costs and subsequent inflation. However, correlation is not causation – to address this question properly, CQRS estimate the effects using a formal regression analysis.

Regression Results

To estimate the causal impact of trade costs on the rate of inflation (using the Consumer Price Index measure), CQRS control for a variety of other macroeconomic variables. These include the GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth rate and the unemployment rate.

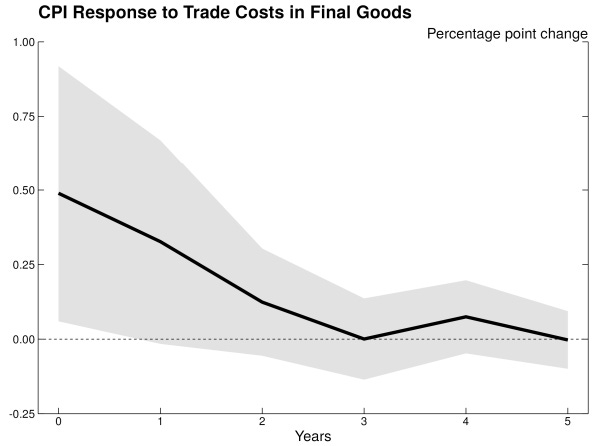

CQRS looked at the impact of trade costs in a given year within a multiple decade span (e.g. 2000) on inflation in the following 5 years (e.g. from 2000 to 2005). CQRS found that a 10 percentage point increase in the final good trade cost, increases CPI inflation by 0.5 percentage point in the first year, and then gradually dissipates over the next few years. In total, CPI inflation goes up by 0.9 percentage points. Visually:

For intermediate goods, the pattern is slightly different. A 10 percentage point increase in the trade costs of intermediate goods leads to a smaller first year increase in CPI inflation – 0.3 percentage points. However, CPI inflation remains elevated for all 5 years, cumulatively increasing CPI inflation by 0.8 percentage points.

However, it is worth noting that these estimates are quite imprecise. Due to the fact that trade costs do not change frequently (as shown in the prior graphs), regression analysis3 on its own cannot give us the answer on whether tariffs do lead to higher inflation. For this, CQRS needed to build a model.

Modelling the Economy

In the CQRS model of the world, there are two types of firms – a producing firm and a retailing firm. The producing firm uses labor (workers) and intermediate inputs (e.g. steel, wood, machines) to produce a good (e.g. a type of truck) that is sold only to the retailer. The retailer can then sell this good for ‘consumption’ purposes (e.g. a truck for personal use) or can sell the good to another producing firm (e.g. a cement truck to be used as an intermediate good in the creation of another good).4

The reason CQRS have these two types of firms is to differentiate between final goods (a personal truck) and intermediate goods (e.g. steel) since CQRS are interested in seeing how the economy will react to trade costs impacting the different goods.

The assumption in the model is the producing firms (i.e. the truck maker) prefer a variety of intermediate inputs (e.g. steel and aluminum) in their production, if cost wasn’t an issue. For example, rather than just having steel, a firm would make better trucks with steel and aluminum. Thus, each intermediate input is not perfectly substitutable. In this particular model, firms are always interested in importing as not all intermediate goods are available domestically. The key cost to importing, however, is the trade cost.

Impacts of Different Trade Costs

Armed with the above model, which is set to mimic the US economy, CQRS experimented with changing the trade costs. Using the US tariff increases on China in 2018-19 as an example, CQRS increased both trade costs of final goods and intermediate goods by 20%. The following charts reflects the contribution to inflation (and GDP) of each of the trade costs:

As can be seen, the final goods trade cost shock (blue) increases inflation substantially in the first 4 quarters and dissipates quickly after. On the other hand, the intermediate goods trade cost shock contributes to elevated inflation for several years. Why?

This persistence occurs because the real marginal cost of production for the producing firms, which depend on the intermediate good, is now higher. Because real marginal costs are higher, inflation spikes (a more in-depth analysis of this mechanism was covered here).

Tariffs on Intermediate Goods – Inflationary

The CQRS paper has illuminated a key fact in the tariff-inflation debate:

The inflationary outcome of tariffs depends on what type of good the tariff is placed – intermediate good (persistent inflation) or final good (one-off inflation).

The CQRS paper helps explain why both sides of the debate are right. For example, many economists argued that the tariffs that were placed on washing machines in 2018 only resulted in temporary inflation (something I originally disagreed with). Now, however, it appears they were correct. Since washing machines are a final good, the inflationary effect of washing machine tariffs will be short-lived. On the other hand, the inflationary impact of steel tariffs will most likely be much more persistent.

The cool thing about economics is that the more we dig into a topic, the more nuanced the results. The CQRS paper shows us that treating every tariff identically can lead us astray. Moreover, it turned out that the disagreement between economists appears to have been caused by this assumption – i.e. treating every tariff identically. Which brings me back to the key theme of Nominal News – always be clear about assumptions. Unfortunately, even economists, me included, may not realize what assumption is being made.

Appendix

It is impossible to observe trade costs. However, trade costs can be inferred based on the observed trade flows between countries. Note, this analysis does depend on several assumptions, since we have to factor in how traded goods are used.

The basic model used by economists assumes that there are two types of firms in each country – production firms and retail firms. The production firm makes a good that is unique to each country. This unique good can be either sold to a domestic retail firm or a foreign retail firm. The retail firms (domestic or foreign) combine production goods (both domestic and foreign) into one ‘final consumption good’ (the things and services individuals in a country consume). This ‘final consumption good’ cannot be traded. As an example, Arendelle produces tuna salad while Northuldra produces bread. The tuna salad (bread) can be consumed by Arendelle (Northuldra) residents or it can be traded. If traded, Arendelle and Northuldra could then each make tuna salad sandwiches. Note, these tuna salad sandwiches themselves cannot be traded (no one likes soggy sandwiches).

We can assume that residents of Arendelle generally prefer tuna salad sandwiches to just tuna salad (similarly for Northuldra). Thus, based on the model parameters (i.e. how much they prefer tuna salad sandwiches to just tuna salad), which are derived from other research, we can infer how many tuna salad sandwiches Arendelle residents would like to eat, which in turn tells how much bread Arendelle would like to import. The difference between the actual observed imported amount of bread and the desired amount of imported bread must therefore reflect the trade cost. That is, Arendelle chooses to import less bread than they optimally would, because it is expensive to import.

Questions from Readers

We’ve received a few questions from readers. Below are our answers:

How is the Consumer Price Index basket sample measured?

The main source for the data is the Consumer Expenditure Survey. There are 13,000 households that participate in this survey each quarter. A selected household is surveyed for 4 quarters. There are two components of the survey: a quarterly interview survey during which larger purchases are discussed, such as rent and durable good purchases; and A diary survey – households track all their small purchases, such as groceries, in a ‘diary’.

What can cause real wages to stagnate while the level of desired mark-up by firms increases?

There are two components to this question. First, real wages can stagnate when the bargaining power between firms and workers change. With higher unemployment, workers typically are unable to bargain for more wages. Second, the desired mark-up level is a ‘macro-economic’ aggregate of all firms. What can move the level of desired mark-up is competition and behavioral change. Higher competition should theoretically push mark-ups down. With regards to behavioral change – I’m referring to some recent research on how the internet has made us less price sensitive. This allows firms to charge higher mark-ups.

To elaborate on this point – central banks can prevent inflation from increasing, in response to tariffs, by responding very aggressively with increasing interest rates. This would be a sub-optimal policy of the central bank, as it would entail many costs on citizens (a recession, higher unemployment and lower wages). Thus, the central bank will allow for inflation, to more gradually adjust to the new tariff reality.

These costs also pertain to domestic goods.

For regression analysis to provide robust results, the variables used in a regression need to have variability (i.e. the data changes from year to year). Since tariffs are often locked at the same level for many years, the variability of tariffs is low.

Note, we are abstracting away from the fact that a real firm might not be able to easily switch production between a personal truck or a cement truck. However, in the real world, there are many producers of trucks, and rather than treating each firm separately, we can simplify by assuming there is one firm that produces trucks, and they always have either a personal truck or cement truck in stock.

As for models; their output is exactly as accurate as the hard data and variables plugged into them. Variables are the easiest to massage since most cannot dispute their accuracy; they are educated guesses at best. Hard data can be vetted by some but taken as accurate buy most. Figures never lie, but liars can figure.

Hey, thanks for this, very interesting!

I don't fully understand how the model predicts the impact of tariffs of different goods on inflation. I understand the assumptions in the model, but not how the model predicts the impact. Can you explain how this is done? (I am imagining this the econometrics part, which might be too abstract, even so if you could describe at top level.) Thanks!