How the Internet is Changing Economics

The Internet changed the economy profoundly – but it also changed economics.

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

If you would like to support us further, please consider sharing and liking this article!

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. If you would like to suggest a topic for us to cover, please leave it in the comment section.

The shift to an online, digital culture has not only impacted economic output, but also altered some of our previous beliefs of how the economy and human interactions work. Two recently published working papers demonstrate these changes in online shopping and social media.

1. Online Grocery Shopping

Chintala, Liaukonyte and Yang (2023) investigated whether people’s behavior differed whether they did shopping online or offline. Chintala et al. collected data on a panel of individuals and monitored their online shopping orders that were done via Instacart (a US third-party online delivery service), as well as their offline orders (by having participants upload receipt images from sales). The study focused on grocery and food related sales.

Growth of Online

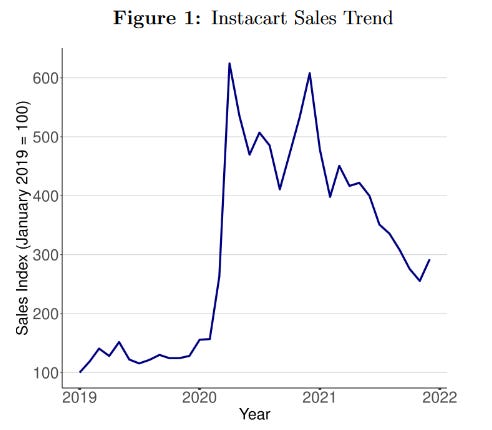

The use of Instacart jumped 6-fold during the Covid pandemic. Although some of the bump in sales due to Covid has reversed, use of the Instacart platform still remains elevated:

Instacart sales, however, still only account for a relatively small amount of all grocery sales – only 4% of grocery sales are done via Instacart, and 9% via other online platforms.. The remaining 87% of grocery purchases are done at physical stores. To illustrate the shopping patterns of a typical household, below are the grocery purchases of a sample household:

The blue circles represent stores where the household does both online and offline shopping, while the yellow circles are offline only. The size of the circle represents the percentage spent at each store.

Establishing Differences

In order to determine the differences between online and offline shopping, it might be tempting to just look at the differences between all offline and online sales. This would not be a good comparison, as that would be capturing the effect of different types of shopping purposes – for example, if a person wanted to grab something that they need now, they might go to the physical store for a quick run. This would be a very different type of shopping purchase compared to the ones people do online, and would be capturing other effects such as convenience.

To ensure the analysis is comparing similar shopping runs, Chintala et al. used machine learning algorithms to determine which shopping runs were “characteristic” trips. Characteristic trips are shopping trips during which the household restocks their groceries. These trips are different from non-regular, fill-in trips to convenience stores or gas stations. During characteristic trips, the average grocery spend (in the collected data) is approximately $72, while for non-characteristic trips the amount spent is $18, suggesting they are inherently different types of shopping runs. Characteristic trips are also less frequent as the graph below shows:

The graph shows how many days pass between repeating a trip of the same type – blue represents characteristic (restocking) trips, while yellow are non-characteristic trips.

Impacts of Online Shopping

Prior to discussing the results – we recommend establishing your own view of what will be the impact of online shopping by thinking about the following hypotheses:

Thanks to online shopping, shoppers buy a wider variety of products

Online shopping baskets have more impulse items like candies and chips

We’ve also added a poll below, in case you’d like to state your hypothesis:

Chintala et al. found that Instacart shopping trips have approximately 10 to 15% lower variety in purchased items than offline shopping. The graph below shows the distribution of purchased items by product category (left figure; an example of a category is “sauces”) and unique product items (right figure; for example, unique items would be a specific brand of sauce):

The variety (both in categories and unique items) bought at physical stores is higher, as the yellow (offline) graph is skewed to the right of the blue (online) graph.

However, maybe online shoppers compensate for this lower variety by purchasing different goods in their next online shopping run? Chintala et al. found the opposite – the shopping basket between two characteristic (restocking) purchases on Instacart are more similar to each other than between two physical shopping runs. The purchased items on an Instacart trip are more likely to come from the same category and be the exact same item between two ‘trips’. Chintala et al. argue that this result can be explained by the “Buy It Again” feature found on the Instacart website, which encourages repeat purchases.

Lastly, Chintala et al. find that Instacart purchases tend to have fewer fresh vegetables (by about 13%), but also fewer impulse buys (by 5-7%). Moreover, Chintala et al. found that shoppers do not make up for these differences by doing an additional shopping run – that is, they do not go additionally to a physical grocery store to purchase either the fresh vegetables or candies, since they did not buy them on Instacart.

Implications

The results of this study have several important implications. Chintala et al. point out that from a business perspective, this research demonstrates that consumers are ‘sticky’ and undertake repeat purchases. From a societal perspective, the fact that online shopping reduces fresh vegetable purchases may be an issue that would need addressing given its nutritional importance.

However, one topic the authors of this paper did not touch upon, is the impact of online shopping on inflation. Consumer ‘stickiness’ to products via the ease of one-click online shopping may allow retailers to increase mark-ups (profit margins), which in turn increases inflation. As we discussed in our previous post on the causes of the recent inflationary surge, Cavallo and Kryvtsov (2022) demonstrated that product stock-outs (when certain items are out of stock) significantly impacted inflation (a 10% increase in stock-out increased inflation by 0.1 percentage points). These two strands of research suggest online shopping can reduce price sensitivity, allowing retailers to charge higher prices, especially when a specific item is in low stock, increasing inflation.

2. Value of New Markets and Products

Typically, when we think of new products and markets, we assume that it can only increase welfare. The idea is simple – if people choose to acquire a product or use a service, they must derive a benefit from it. Those who do not use the product/service gain no benefit from it, but also aren’t worse off, meaning their welfare sees no change.

However, although this assumption sounds logical, and is applicable to most products and services, it does not have to be true if there are ‘network’ effects – that is, the value of a service or product depends on others using it. Bursztyn, Handel, Jimenez and Roth (2023) looked at such a case, where a product market became a collective trap for most – social media.

The Experiment

Bursztyn et al. conducted a series of experiments to elicit the value college students get from using one of two social media networks – Instagram or TikTok. To do so, Bursztyn et al. conducted a sequence of experiments. In the first experiment, the researchers asked participants how much money they would be willing to accept to not use Instagram or TikTok for 4 weeks. Most participants asked for a positive amount of money, with only a few saying they’d do it for free.

In the second experiment, participants were asked, in a plausible scenario, whether they would like to disable Instagram (or TikTok) for all students at their college for 4 weeks, including their own account, or not disable anyones’ account. If the participant chose to disable the accounts, all students, besides the participant, would receive the amount of money established in the first experiment, as this is how much each student would be willing to be paid to have their account disabled for 4 weeks.

Now the answer to the question in this second experiment basically tells us if the participant sees any benefit from the existence of Instagram or TikTok. If the participant chooses to deactivate everyone’s account that means that the existence of the social media network generates negative value to them. This is because they do not receive any payment for choosing to deactivate everyone’s account and they could have chosen to simply keep all accounts, including their own, active.

Additionally, if the participant chose to disable everyone’s account, the participant was given a follow up question – how much would they need to be paid to change their decision – that is to keep everyone’s account active. This allowed Burszytyn et al. to estimate the negative value of the social media networks in question.

The Network Trap

The results of the experiments were the following:

The dark blue, first column shows the average amount participants needed to be paid to turn off just their own accounts for 4 weeks (experiment 1). It ranged from $59 for TikTok to $47 for Instagram (i.e. the value of staying on TikTok and Instagram is $59 and $47, respectively). The red, third column, were the results of experiment 2. Participants need to be paid $28 and $10 in order to keep Tiktok and Instagram active for everyone, respectively. Without the payment, they would prefer to disconnect TikTok and Instagram for all their fellow college students and themselves. The last, pink column, shows the results of experiment 2, but for people who do not use TikTok or Instagram. Participants that did not use TikTok or Instagram, would need to be paid even more to prefer keeping the social media apps active for others.

These results tell us two things:

Instagram and TikTok appear to generate negative welfare on average (red bar). The negative welfare impact is larger for non-users of these social media networks (based on the results from the second experiment).

If others are using Instagram or TikTok, participants prefer to use these networks, as this is a decision that increases value for them (based on the results from the first experiment).

These two results together imply a form of collective trap – even though it appears we would all prefer if these social media applications did not exist, since some people are using Instagram or TikTok, we would suffer larger welfare losses (the value of the dark blue bar in the graph above) if we individually chose not to use these applications. This result is even more striking, if we emphasize the fact that the experiments did not ask participants to turn off all social media – just one app. Participants could use other social media apps if they were to deactivate Instagram or TikTok. Even though the participants clearly state that Instagram and TikTok are bad for overall welfare, participants still find it preferable to keep these apps, since others are using them.

Brief Aside

As a brief aside, there is always a slight caveat to these types of experiments – do we believe that participants answered the questions truthfully? Previously, we discussed it in the context of estimating the value of gift giving. Bursztyn et al. conducted a variety of additional tests to ensure participants are truthful, including additional questions to test if participants were paying attention, as well as running an identical experiment where the app that was to be disconnected was Google Maps – an app that has a direct practical application. These additional tests suggested that the results mentioned above were valid.

Other Context – iPhones and Luxury Items

Bursztyn et al. also looked at whether this collective trap result occurs in other situations. Turns out that a similar outcome was found regarding luxury brands and new iPhone models. Using surveys, Bursztyn et al. found that 44% of luxury brand owners (who on average owned 2 luxury brand pieces) would prefer a world with no luxury brands. For individuals that owned no luxury brand, 69% preferred a world with no luxury brands. Regarding new iPhone models, 91% of iPhone owners would prefer if Apple released a new iPhone model every other year rather than every year.

Conclusion

The two studies discussed today challenged several very common economic assumptions. Bursztyn et al. highlighted how new products and markets can explicitly reduce welfare, even though our economic intuition would assume that it is impossible, since any product that is demanded should at worst have no impact on welfare.

Chintala et al. showed how online shopping may make us less responsive to prices, even though the Internet has given us access to more information. This is especially relevant in light of our last week’s post on potential antitrust violation by Amazon in their Amazon Marketplace tool. Reduced price sensitivity may also have contributed to some of the elevated inflation we witnessed over the last few years.

The digital economy has undoubtedly had many positive effects on the economy. However, digitization has also impacted some of our prior understandings of economic interactions and behaviors. This has occasionally resulted in economy-wide negative outcomes that may need to be addressed via policy interventions.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Apricitas Economics discusses the recent inflation data. There is a lot of disinflation in the pipeline.

On the topic of prices and inflation – ryan sutton discusses the increasing prices in the New York restaurant scene.

On a different topic – with the recent release of Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, Troy Tassier discusses what really was the greatest threat to Napoleon’s army.

Photo by Lisa Fotios.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

The End of Inflation in the US? (June 25, 2023) – after the inflationary surge that occurred during 2021-2023, the June 2023 inflation data suggested that US inflation has come back down to the 2% target. Did it come down due to the Federal Reserve interest rate hiking policy or was it driven by the normalization of supply chains?

Work Requirements (May 29, 2023) – work requirements are considered to be a helpful policy to incentivize people to work. Empirically, the data shows that this is not the case. It does not increase participation in the workforce and hurts the most vulnerable individuals.

The True Value of the Infrastructure Bill (November 20, 2022) – the US passed the Infrastructure and Jobs Act, which has significantly increased infrastructure spending. How impactful will it be and why more is needed.