Surveys, Assumptions and Understanding Housing Supply

A Financial Times opinion piece discusses research claiming that people do not understand how housing supply impacts prices. But is that true?

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

If you would like to support us further, please consider sharing and liking this article!

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. If you would like to suggest a topic for us to cover, please leave it in the comment section.

This is part 2 of a two part series. Please see Part 1 here.

An opinion piece in the Financial Times (FT) “Repeat after me: building any new homes reduces housing costs for all”, discussed the issues of housing, housing costs, and housing supply. The headline – that building any type of new home, whether low cost or luxury – reduces housing costs for all is correct, as economic research has shown. However, some other parts of the piece are questionable. Below is a brief overview of the FT piece – if you read our previous article from October 12, feel free to skip to the introduction.

Overview of the FT piece

The main claims of the FT piece can be summarized as follows:

People misunderstand how increasing housing supply will affect prices.

Building any type of housing (luxury or affordable) will improve housing affordability.

Based on the author’s calculation, policies such as upzoning (allowing for higher density construction on a plot of land) can have a very large effect on housing prices – a 25% reduction in prices – which stands in stark contrast to research we described here, where prices only fell by 1.9%.

We agree with claim 2. Both empirical and theoretical research have often demonstrated this to be the case, and the FT piece does a good job of explaining it. Basically, building luxury housing allows high income individuals to upgrade their home – but now their previous home is available for others who have lower incomes.

However, claims 1 and 3 have certain issues.

Introduction

In yesterday’s piece, we talked about how the FT opinion piece incorrectly estimated the effects of upzoning by improperly using a comparative method. Today, we will focus on another claim made by the FT piece: that people misunderstand how increasing housing supply will affect prices.

Claim 1 – Do People Understand Housing Supply

Summary

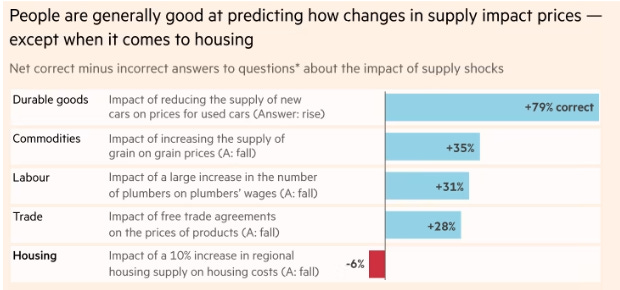

Regarding the claim that “people misunderstand how increasing housing supply will affect prices”, the FT author discusses an interesting finding from a research survey by Nall, Elmendorf and Oklobdzija (2022) shown below:

The study claims that, to the question of what would happen to house prices if housing supply increased, more people responded incorrectly (that prices would rise) than correctly (prices will fall). Standard economic theory predicts that if you increase supply of a good (regardless of what it is), then, holding all else constant, prices would fall. There are no issues with the theory, so why do people respond incorrectly?

The Holding All Else Constant Assumption

One issue with this type of survey question is that it requires the surveyed to make the very strong assumption of holding all else constant. The holding all else constant assumption, also referred to as ceteris paribus, is a critical assumption needed to study causality.

For example, upon hearing the housing supply question, rather than thinking prices would fall, individuals might be wondering why there is a major housing supply increase. If, for example, the reason housing supply went up is because our city became more attractive to people, then we may think prices may go up, rather than fall. But the holding all else constant assumption tells us not to assume any of that – nothing has changed, only housing supply went up.

To me this feels like a very difficult assumption to accept in this scenario and therefore people may not be thinking in that way. In other supply shock scenarios, it is easier to maintain the holding all else constant assumption. For example, regarding grain, the survey presented a scenario in which grain production increased because of a new fertilizer. To violate the holding all else constant assumption, we would need to consider, for example, whether this increased grain production could result in higher population which could in turn increase demand for grain, pushing grain prices higher. This is a convoluted example, because it is not easy to come up with one, suggesting that in the grain scenario, the holding all else constant assumption is easy to accept.

On the other hand, when we think of a large increase in housing development, it’s understandable to assume that it may be caused by some other factors that could drive prices up. As already mentioned, if there is more housing development, it is easy to assume that it may be driven by increased demand to live in that area.

To give an example of how violating the holding all else constant assumption can play out, let’s think of the US lotteries. Recently, US lotteries have been attaining astronomical jackpots, often surpassing $1bln. We could conduct a survey asking people whether you expect to win more money if the jackpot is higher. If we hold all else constant, the answer should be ‘yes’. However, a person may correctly assume that the higher the jackpot, the more people will play the lottery, the higher the probability of splitting the jackpot. In that case, you’d receive less money when the jackpot is higher. Thus, in reality, we could observe that a higher jackpot means lower winnings, even though the correct answer to the hypothetical question would be the opposite.

Another Issue – Spill-over Effects

The holding all else constant assumption also means that we should not take into account any spill-over effects stemming from the change. Higher housing supply usually results in increased density. Increased density has been shown to improve surrounding amenities (for example, a grocery store or coffee shop is more likely to open in a high density area). Better amenities, in turn, increase house prices and rents (for a good reason). Thus, after upzoning, prices, when taking into account all other effects, might not go down, which would explain why survey respondents may think increased supply increases prices. But, the holding all else constant assumption tells us to hold all these things fixed – that is, assume amenities do not change.

The Underlying Study

The Nall et al. survey on supply and prices did attempt to address some of the issues with the holding all else constant assumption, by phrasing questions in various ways. For example, each survey respondent was given a specific hypothetical scenario explaining why housing supply is increasing – ‘suppose construction costs decrease resulting in more housing’ or ‘suppose areas are deregulated resulting in more housing’ – and were then asked to answer whether house prices will fall or not.

They found that there was almost no difference in responses among survey respondents based on the particular scenario of why housing supply is increasing. We could have expected that people may respond differently if the cause of the housing supply increase is deregulation or lower construction costs. Moreover, Nall et al. found that the proportion of people responding to these questions incorrectly (i.e. that prices would increase) did not depend on whether the person was a renter or homeowner. One would have expected that since renters may prefer lower prices and homeowners may prefer higher prices, renters and homeowners may answer these survey questions differently.

Nall et al. interpret these findings to mean that this incorrect understanding of how housing supply increases impact prices is universal. However, this lack of differences in answers by different groups might also be explained by the fact that people do not entirely understand the question – and are not sticking to the holding all else constant assumption. The study design does not allow us to definitely rule out whether people universally misunderstand the impacts of housing supply or people universally do not adhere to the holding all else constant assumption.

Differing Results

Some evidence pointing to the latter explanation that the people do not abide by the holding all else constant assumption can also be found in the Nall et al. study. The authors ran two versions of the supply and prices survey: the pilot and main study. Surprisingly to the authors themselves, they got significantly different results in the two studies, although in both cases they asked very similar questions to a large sample of participants. The main study showed fewer people answering incorrectly (it is worth noting the FT piece showed results of the pilot study).

The concern here is that running similar studies which show differing results typically suggests that the results are not repeatable meaning they are likely to be spurious.

“People Like Me”

Nall et al. also found that slightly changing the phrasing of the question – instead of asking about how would prices change if there are more houses available, they asked about how would prices change if there are more houses available for “people like me” (survey respondent). This resulted in more people answering the question correctly and stating that prices would fall.

Changing responses when the framing of the question is slightly altered also points to an issue regarding accepting the premise of the question. Moreover, this altered framing of the question suggests that people may perceive housing as a segmented market. When people hear about increasing housing supply, they may assume it refers to increased luxury housing, which they cannot afford. They may believe that luxury housing and affordable housing are segmented markets – that is, one market does not impact the other. Although this is also incorrect (housing markets are not segmented in such a way, and construction of luxury homes will improve overall affordability), it is understandable why individuals may perceive this to be the case. For example, if we asked what would happen to restaurant prices, if a new luxury restaurant opened, saying that restaurant prices would fall does not seem likely.

Are the results overblown?

Lastly, it is worth noting that the main result presented by Nall et al. is the fact that more people said that the house price would rise rather than the correct answer that house prices would fall due to increased housing supply. However, there was a large block of individuals that answered that prices would not change. Technically, this answer is also wrong. However, it is not surprising since many studies have shown that housing prices do not respond much to housing supply increases (when taking into account other effects). Thus, this answer can be reasonable. When taking into account the individuals that said that housing prices will be lower (the correct answer) or there will be no change in price, approximately 60%-65% of people answer approximately correctly.

Summary

Recapping the key FT piece claim:

Claim 1: People misunderstand how increasing housing supply will affect prices.

The correctness of this claim is difficult to judge, because, although the interpretation of the study is correct (that people incorrectly think that prices will rise when housing supply increases), the issue remains whether individuals actually understand the survey question the same way economists do. If we assume that an individual does not adhere to the holding all else constant assumption, the results of the survey do make sense. If we look at the studies discussed in our post on October 12, policies such as upzoning that are intended to increase housing supply do not lead to significant housing supply changes or even fall in prices. Actually, housing prices tend to continue to increase, even when policies such as upzoning are enacted, as can be seen in the Auckland data below (of course, without upzoning, house prices could have been even higher). Thus, maybe it shouldn’t be too surprising that people might respond to a survey with hypothetical questions regarding the impact of housing supply ‘incorrectly’, since what they observe is housing prices going up regardless of policies.

Conclusion

Generally, survey data is not a good source of information, as people do not have incentives to respond to them honestly. Drawing results from surveys is typically not a good way to approach questions. Moreover, in the survey described by the FT, it appears there could be an issue in knowing and accepting some of the premises the survey was trying to make, especially around the holding all else constant assumption. Therefore, we shouldn’t draw too many conclusions from such a study.

Overall, the FT piece touched upon a lot of economics – some of it good, some of it not so good. The topic covered is very important – housing affordability in the US and in many countries is close to an all time low. It is important to discuss what type of solutions might work. Building any type of housing is good for housing affordability. Upzoning, to the best of our knowledge, also improves affordability but to a very small extent. It also comes at a large cost to current homeowners, as we discussed previously, making it a solution that is unlikely to be favored universally.

Housing affordability remains a complex issue with no easy answers that can satisfy all. Economic research so far has not been able to pin down any great answers. One potential avenue, which we discussed, is the increase in public transit, as it may improve housing affordability, without making homeowners worse off. But there is a lot more research to be done.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: An update by Pascal Michaillat on the labor market and whether we are at an efficient level.

Article: This week, the September inflation data came out. Inflation continues to cool, suggesting the Federal Reserve is done increasing interest rates.

Tweet/X: As part of a lawsuit against Amazon, we leaned about an algorithm used by the e-retail giant to raise prices and seeing if competitors would follow.

Photo by Phillip Birmes.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Discrimination in Real Estate (September 17, 2023) – unlike explicit discrimination, statistical discrimination is less talked about. However, it has significant impacts on outcomes for people impacted by it. Real estate agents, often unaware of their own statistical discrimination, end up perpetuating outcomes for minorities.

The Work from Home Illusion: Is It? (July 15, 2023) – the Economist covered several work from home studies. The conclusions the Economist drew from them, however, were quite wrong. What did these studies actually say, and why work from home might be the optimal form of work.

Marriage Preferences and Gender Outcomes (March 26, 2023) – how partner preferences impact the glass ceiling.

Good read!