Housing and Public Transit in Cities

Solving the housing affordability issue is not simple. Would developing city transit connections improve it?

Substack has released a new feature called Substack Notes in which we will be posting interesting information and developments that would be too short for a full article. It is also a good tool to communicate and ask questions! If it is something you may find interesting, you can head to this link!

Introduction

In our last article, we discussed why housing deregulation and removal of zoning laws will most likely not resolve the housing supply and affordability issue. This is due to the fact that current homeowners and landlords can, in most cases, easily replicate these rules if they were removed via the formation of some form of ‘private’ government. This can be done via the creation of Homeowner Associations (HOAs) or, more extremely, the creation of a new municipality, town or city (seceding from a local government).

Although it is beneficial to discuss why certain solutions might not work, it is also helpful to address what could. At the end of my piece, I mentioned that public transport should be developed to improve housing affordability. Would that actually work?

How Transit Can Impact House Prices

Transit lines, especially rail-based transit lines, have long been studied by economists. First, it is helpful to consider in what ways can housing and transportation interact with each other. From the perspective of an individual, it’s not only the cost of the house that matters to them, but also the cost of transportation. Getting to and from work or to any entertainment venue (economists typically refer to anything that provides some positive impact as “amenities”) is costly. These costs typically consist of two components – the direct cost of transportation (e.g. transit tickets, car fuel) and the indirect cost or opportunity cost1 of the time it takes to get there. Naturally, the location of the house and the distances to work and amenities impact the transit costs. Thus, we should expect if transit costs go up, house prices go down.

Based on the above, we might assume that a new transit line would unambiguously increase house prices and rents of houses that are within a certain radius of the new transit line stations. But that is not necessarily true. Firstly, for a new transit line to be beneficial it actually has to reduce the costs of travel. It either must be cheaper or faster, or both, to the current alternatives. Secondly, a transit stop or station can have negative influences on the surrounding area, especially in the immediate area of the station. This can include disamenities (for example, there is more congestion and noise), but also potential for increased criminal activity. There are therefore also negative pressures on house prices in the vicinity of new transit lines.

One other way a new transit line can affect house prices is through its general equilibrium effect. When economists consider general equilibrium questions, the focus is on how a new policy (in this case a new transit line) affects the wider economy. Above, we discussed only what is known as partial equilibrium – the impacts of a new transit line in the area of this transit line. A discussion of general equilibrium effects would focus on the impact on the whole city.

A new transit line, especially in an area that is not connected by transit, opens up a new residential market for many. Thus, renters and potential homebuyers can move into a different neighborhood, lowering demand for housing in other parts of the city. A newly connected area can also increase the value of houses already connected to the transit network, since now these previously connected areas can travel to a wider range of city neighborhoods.

Additionally, a new transit line may also lead to immigration to the city – this immigration could come from unconnected parts of the city and other parts of the country. This would increase overall housing demand, but at the same time, as there are more people, there would be an increase in overall economic activity in the city. This is typically referred to in economics as the agglomeration effect, which is the impact of firms and people clustering in an area, which results in lower costs of production, more innovation, and overall, more economic output (a famous area known for the agglomeration effect is Silicon Valley). Thus, the higher economic activity from immigration can potentially increase wages in the affected area.

Immigration can therefore have ambiguous effects on housing affordability in the city – although prices for housing go up due to more demand caused by increased population, the incomes of everyone in that area seeing more immigration could increase due to greater economic activity. Higher incomes makes housing more affordable. Which effect ends up dominating is unclear.

Overall, a new public transit line can have mixed effects. So what do research findings have to say about all the potential impacts?

Research Evidence

House Prices

There are many studies that have looked at the impacts of opening new transit lines in various cities around the world. Most of them usually focus on the impact the new transit lines have on house or rental prices near the new line. Many of the studies conclude that new transit lines increase nearby house prices by approximately 1 to 3 percent for areas that had not been previously connected. There is a bit of variation of the effect – houses right by the new transit stop typically lose value due to the disamenity of the new transit stop, while the largest benefit goes to houses between 2000ft (600m) to 3000ft (1000m) away from the transit stop. This implies that the value of new transit lines gets capitalized into the house price.

There have, however, not been many studies that looked at the wider impacts of new transit lines (the general equilibrium effect). This is because testing all the interacting effects at the same time is nearly an impossible task unfortunately. There are many different moving elements and therefore, establishing causality is complex. Even determining the appropriate time frame to study the impacts of a new transit line is contentious. The effects of a new transit line may take years to materialize, but during that time many other things change as well, making determining causality difficult.

A recent study by Chernoff and Craig (2022) looked at the impact of adding new metro stations in Vancouver. They found that adding the new stations increased the prices of housing near these new stations by about 2.1 percent (in line with previous studies). They also found that houses that had access to pre-existing stations also saw an increase in value, albeit lower at 1.6 percent. Furthermore, Fesselmeyer and Liu (2018) looked at a similar transit expansion in Singapore. They found comparable effects – houses near pre-existing stations saw an increase in value as well.

The price effect on housing located in areas with pre-existing transit connections is driven by the two forces:

Substitutability/Competition: a new transit line increases accessibility to a new neighborhood with housing, thus giving a potential buyer/renter a wider market to choose from. This increased competition will reduce prices of the houses next to pre-existing stations.

Complementarity: a transit line to a new region, gives people access to a neighborhood they might not have access before. Being able to access a neighborhood is a benefit, making it valuable and thus, increasing prices of housing in areas with pre-existing stations.

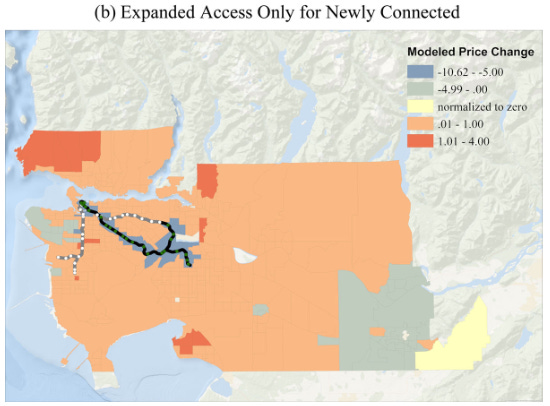

Chernoff and Craig looked to decompose these two effects to establish the size of each of them. The authors ran a hypothetical scenario simulation, in which only individuals that live in the newly connected areas were allowed to use the newly built stations. People located next to pre-existing stations were not allowed to use the new lines. Thus, the people that lived next to pre-existing stations were only impacted by substitutability/competition effect but not the complementarity since they’re unable to travel to the newly connected region on the transit line. In this scenario, house prices in areas with pre-existing stations fell by approximately 1 to 1.5 percent. The heat map below shows in black, the pre-existing metro line and in gray, the newly constructed line. The price changes are in tens of thousands of Canadian dollars.

The above suggests that the substitutability/competition effect significantly dampened the price increase for houses next to pre-existing stations. Although no additional housing was built, the new transit line “increased the supply of housing” by lowering the transportation costs. Without this substitutability/competition effect, house prices next to the pre-existing stations would have gone up even more than the stated 1.6 percent.

Xin and Tao (2022) found slightly different results regarding the impact of new subway lines on areas with pre-existing stations. They looked at the case of Beijing and the rental market. Rents in apartments near the new stations increase by approximately 2 to 5 percent. However, apartments further away from these new stations saw rent reductions, suggesting a ‘siphoning’ effect (i.e. the newly connected areas ‘siphon’ people out of other areas of the city). However, the authors do not differentiate whether this is driven by the fact that houses with no stations are seeing a big drop in value or whether all houses (even pre-connected ones) see a drop, including ones that are located near pre-existing stations.

One additional way to see the impact of the new transit line is to examine how the average income in the areas change. Using their model, Chernoff and Craig found that average incomes go up in both in the newly connected area and the previously connected, as shown by the heatmap below.

This implies that sorting is occurring in the city, whereby certain higher income households leave the previously connected area and move to the newly connected area. As they were relatively ‘poor’ in the previous area (i.e. there were many richer people than them living in the neighborhood), average incomes increased in the previously connected areas. However, since the people that moved to the newly connected area are richer than the individuals who lived there prior to the transit expansion, that area also experiences an increase in average income. This implies that new transit lines do result in individuals moving from a high cost area to a lower cost area.

Welfare Analysis

In terms of welfare outcomes from the new transit lines, there are many different components to consider, such as house price values and rents, increased accessibility to more areas, improved amenities, and increased economic activity. Moreover, whose welfare should we measure – should we put more weight on homeowners or renters, should we only focus on current residents and not on immigrants, should we worry about gentrification. These are just some of the difficult choices in determining how to measure welfare outcomes.

In Chernoff and Craig’s work on the Vancouver new transit line, the authors focused mainly on the welfare of current residents along with changes in house values and overall amenity level (amenity level was proxied by the average income in a region). Welfare increases on average due to the new transit lines. Although house prices of both newly-connected and pre-connected areas increase when building a new transit line, the accessibility to the new neighborhood, which has relatively cheaper housing (measured in absolute dollars), compared to the previously connected areas, means that total housing plus transport spend would fall for many of the low income individuals. (To illustrate: suppose in pre-connected area A, a house costs $100,000, while in not-connected area B, the house costs $90,000. Assume transportation was only doable by car, which would cost annually around $5,000. A new transit line to area B, that has minimal costs to use, increases home values in both areas by 2%. So in area A, the house costs $102,000, while in B, it costs $91,800. But since now you can purchase in either A or B thanks to the transit line, your overall housing spend goes from $100,000 to $91,800. Even though prices went up, you can spend less.)

For homeowners, the new transit line increases their property values due to value creation offsetting the additional competitiveness. However, there are potentially some welfare losses for individuals living in areas that were never connected to transit lines.

To truly assess welfare, we would need to include many additional factors. For starters, we would need to take the cost of building the transit line into account, which can be very large for such projects. The cost of expanding the subway network in Singapore was approximately $5bln. However, based on Fesselmeyer and Liu’s calculation, the increase in property values of the connected transit stations amounted to about $455mln, which is nearly 10% of the construction cost. This does not include the benefits to the newly connected region. Some have proposed that part of the transit line costs can be funded by additional property tax assessments (either increasing the tax rate or re-valuing the properties to account for their higher price).

There are also many other potential benefits from new transit lines such as reduction in pollution and congestion which generates economic value. Increased economic activity can also result in higher wages and an overall better allocation of resources.

Conclusion

Prior to commencing research on this topic, my assumption was that improving transit, especially in cities, would reduce house prices and rents in all other areas of the city. I assumed demand would reduce significantly in other more expensive parts of the city, and would increase substantially in the newly connected area. My assumption appears to be wrong. Prices of previously connected areas seem to increase (possibly Beijing being an exception).

However, there is evidence that overall housing with transportation included becomes more affordable. Although house prices go up, there is an offset in the transportation costs, making the total spend on housing and commuting reduce. Moreover, it appears the substitution/competition effect is substantive. Since models show that individuals move into areas with new transit lines, they must be better off (otherwise, they wouldn’t do it). Nonetheless, it would be beneficial to have a more direct study to determine that this is the case – is housing affordability increased when transit improves due to the reallocation of city inhabitants to different parts of the city.

The value of new transit lines might also depend on the type of cities. In Vancouver, the new transit line appears to increase welfare. On the other hand, Severen (2021) argued that the building of a new light rail line in Los Angeles might not generate as much value as expected relative to the costs. Severen’s conclusion states that single transit line improvements in cities that have been designed for cars and have multiple city centers might not be too beneficial to the local community. However, the issue of housing affordability is less prevalent in more spread out cities.

Overall, based on my reading of the evidence, building transit in dense cities appears to improve housing affordability as well as total welfare (though not necessarily improving welfare for everyone). Moreover, since transit lines do not reduce the value of existing expensive houses, there will not be as much opposition to their development, as is with the case of housing deregulation and removal of zoning laws. The additional benefits of cleaner air and reduced congestion also create value. All of this together, suggests that improved transit would be beneficial to the city.

Please feel free to share this article!

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones:

Housing – Will deregulation fix everything? - would removing zoning laws and housing regulations lead to an increase housing supply and improve housing affordability.

Inflation and Expectations - how should we think about the recent inflationary spike and what needs to happen for it to come down.

Early Child Investment - Child Tax Credit - the benefits of the expanded child tax credit to society.

Cover photo by 39422 Studio.

Opportunity cost is the value of what one could have done instead. In this case, instead of spending time in transit, one could have gone to the gym.

Fantastic article - very interesting