Book Recommendation – Economic Fables

Ariel Rubinstein's "Economic Fables" is a great, albeit not your typical, introduction to economics and economic thinking.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

Our updated goal for 2025 is to hit 10,000 subscribers:

If you would like to support us further with reaching our subscriber goal, please consider sharing and liking this article!

A reader asked me what book I would recommend to learn about Economics. I never really put much thought into this question before, so it was a good opportunity to write about it. One book that came to mind, which I read during graduate school, was Ariel Rubinstein’s “Economic Fables”.

This is probably not a standard choice, so let me explain why I think it is a helpful introduction to economic thinking.

Economic Fables

I will preface that the book is not only about economics – it is also a partial auto-biography and Rubinstein’s thoughts on what Economics is. The book jumps between these strands, which may not be to everyone’s liking.

Moreover, the book itself is not intended to be a textbook or an introduction to the history of economic thought. You will not come out of this book with direct actionable conclusions like how we should organize our economy or what is the impact of any particular policy.

With those caveats aside, I find that the book introduces readers to the concept of economic modelling, or as Rubinstein calls models – “fables”, quite well. As readers of Nominal News may know, I often highlight the importance of stating models, and especially their assumptions, very clearly. Throughout his book, Rubinstein introduces various models and helps formalize thinking around economic behavior. As Rubinstein put it himself in the book:

“In economic theory, as in Harry Potter, the Emperor’s New Clothes or the tales of King Solomon, we amuse ourselves in imaginary worlds. Economic theory spins tales and calls them models. An economic model is also somewhere between fantasy and reality. Models can be denounced for being simplistic and unrealistic, but modeling is essential because it is the only method we have of clarifying concepts, evaluating assumptions, verifying conclusions and acquiring insights that will serve us when we return from the model to real life.”

Example of a ‘Fable’

The first model mentioned by Rubinstein is the Harold Hotelling model. The setup is the following:

Two newspaper vendors have to set up a stall on one street

Each vendor sells the same newspaper at the exact same price (the price is set by the newspaper company);

Each vendor wants to maximize their sales;

Every part of the street has the same number of people walking through it (customers are distributed evenly/uniformly on the street);

Customers will buy the newspaper from the closest newspaper vendor.

The next element in this model is what are the decisions to be made by the ‘actors’, or the newspaper vendors. We only have two actors and their only decision is where to set up their newsstand.

Solution

So where will the vendors set up shop? The solution concept to solve this problem is called the ‘Nash Equilibrium’. In our example, the outcome we need to find is a pair of choices – the location chosen by each news vendor. The ‘Nash Equilibrium’ is a pair of locations such that neither news vendor will want to change their location. For example, let's say each vendor establishes their stand at opposite ends of the street. Vendor A will get all customers from the left end of the street to the middle, while Vendor B will get the rest.

This is not a “Nash Equilibrium”. That is because at least one of the newspaper vendors could make a better decision. For example, Vendor A could move to the middle:

Now Vendor A has captured 75% of the market. However, this is also not the ‘Nash Equilibrium’ since Vendor B has a better decision as well. The only ‘Nash Equilibrium’ is both newspaper vendors setting up in the middle of the street.

It is worth noting that this outcome is not optimal. Everyone would be better off if the vendors setup in the following way:

Each vendor still has the same market share as before (half of the customers), but the most each customer has to walk to the vendor is a quarter of the street.

Usefulness?

We might wonder what is the point of this ‘fable’. This ‘fable’ can be used to explain the behavior of certain producers. Rubinstein gives the example of the choice of sugar content in sodas – just like the newspaper vendors, soda firms typically ‘position’ themselves in the same spot by setting similar sugar levels in their sodas. Another use case is politics and the political positioning of parties – in a two-party system we often see parties position themselves in the center.

Rational Man – Another Concept

Rubinstein also explains the oft criticized economic concept of rational man. Economics is often criticized for assuming that people behave perfectly rationally – something I also used to be critical of when I started my journey in economics.

However, the rational man has been misinterpreted. To give an example (from one of Rubinstein’s class lectures based on the work of Luce and Raiffa (1957)) – suppose from a restaurant menu of chicken and steak tartare, our individual Kristoff chooses chicken. From a restaurant menu of chicken, steak tartare and frog legs, Kristoff chooses steak tartare. Is he rational?

Many would suggest ‘no’. Kristoff could always choose ‘steak tartare’ in both restaurants and the ‘frog legs’ should be irrelevant when making the decision. Thus, Kristoff must be irrational.

But Kristoff’s behavior can be rationalized. The ‘frog legs’ on the menu may tell us that the chef at the restaurant is highly skilled and thus the steak tartare will be very good. On the other hand, in the first restaurant, the steak tartare might not be good. Thus, Kristoff may have a ranking:

Good steak tartare;

Good Chicken;

Bad Chicken;

Bad steak tartare.

Kristoff’s behavior is perfectly rational!

As If

What the rational man assumption actually means is that a person is acting as if they are maximizing some function – the function itself might not be clear to us as the reader. Moreover, this function that is being maximized is an assumption itself. Often we think that this function represents something akin to happiness. But it does not need to be the case.

This notion that a person needs to act as if they are maximizing some function makes economics much more interesting, but also makes economics open to manipulation. It opens us to a wide variety of models and actions that can be studied. But economists can also use this for ‘deception’ as Rubinstein describes:

“Most economists, however, apply economic models to policy questions which require a criterion for the welfare of the individuals to be specified. Economists often identify an individual’s level of happiness with the preferences that explain his behavior. By this approach, if the decision maker chooses alternative A when B is also possible, this means that indeed he prefers A to B. It is far from obvious that the preferences used to describe the decision maker’s behavior correspond to his degree of happiness. Even if the decision maker’s behavior can be described as the result of maximizing some objective function, the objective might not relate to promoting his happiness”.

What is Economics

Throughout the book, Rubinstein grapples with what is the purpose of Economics. As he puts it:

“I would like to advocate another approach, which does not aspire toward purposefulness and the practical use of a model. According to this approach, an economic model is not essentially different from a model in logic. A model in logic is not a prediction of how humans judge whether a phrase in ordinary language is true or false. It is not a recommendation for a thinking person and it is not designed to educate people to think correctly. I contend that economics studies the logic of life, but does not engage in predictions or recommendations. We deal with the wide range of considerations that economic decision makers might take into account. We are satisfied even if the economic model is merely interesting. To be interesting it must focus on considerations that at least some people weigh before making a decision and taking action.”

This passage delineates Economics, as a field of study, from using economics for a ‘purpose’. Moreover, Rubinstein does not suggest Economics itself is necessarily a superior form of knowledge discovery:

“But I am quite sure that if instead of devoting my adult life to economic models I had engaged in a non-academic profession, I would view life from standpoints that are less abstract but no less useful.”

Economics is simply a particular formalized approach to discussing social arrangements.1 However, as Rubinstein points out, Economics itself can often be hijacked:

“I feel attracted to economics as a branch of philosophy and as an academic field in which an intelligent discussion of social arrangements is, or at least can be, conducted. But I also feel disgust for economics as an academic field that tends toward conservatism and helps the strong in society maintain their dominance, and thus serves people for whom I have little empathy.“

The book is available for free here – https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0020

Ariel Rubinstein – Short Bio

Ariel Rubinstein is an economist focusing on theory, game theory and bounded rationality. He is a professor at New York University and Tel Aviv University. One of his main research contributions is the development of the Rubinstein bargaining model.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Matt Bruenig of People's Policy Project goes over the claim of how many Americans are living ‘paycheck-to-paycheck’. Using both self-reported, as well as specific finance data, it appears the claim that 60% of Americans live ‘paycheck-to-paycheck’ may unfortunately be close to the truth.

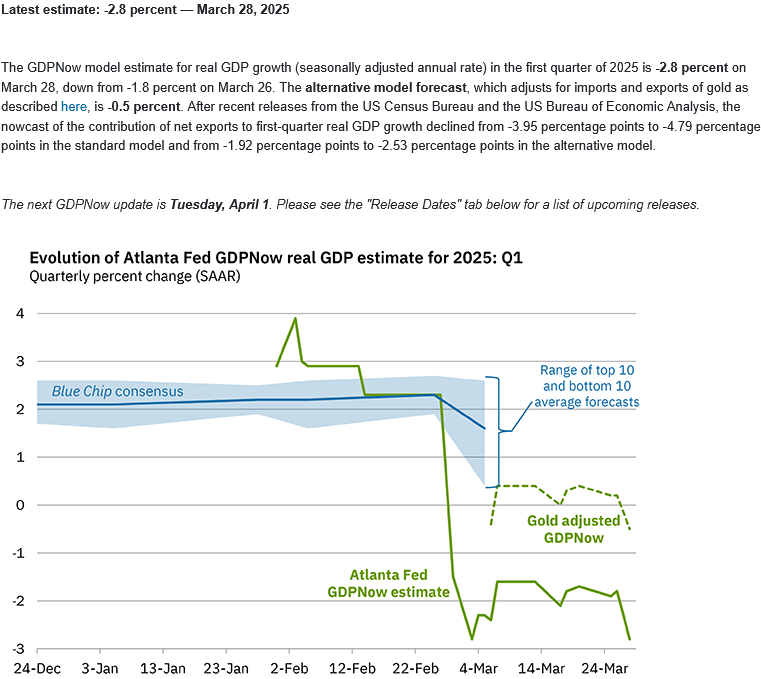

Data: The Atlanta Federal Reserve posted its latest update on the forecast for US first quarter Gross Domestic Product growth. Adjusted for gold imports, the US is currently forecast, according to this model, to contract by 0.5% (annualized).

Report: An analysis by Douglas Irwin demonstrates the Lerner symmetry result - a tax on imports is equivalent to tax on exports.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Did The Federal Reserve Make a Mistake? (August 15, 2024) – a higher unemployment reading has stoked recession fears and led many to think the Federal Reserve made a mistake with keeping interest rates high. Fortunately, closer inspection of the data suggests no mistake was made.

Higher Education – Is It Worth It? (December 10, 2024) – do the extra years of schooling at college increase peoples’ skills or is college just an expensive signal? A recent study suggests it’s the former.

Coffee and Innovation (November 17, 2024) – increasing ‘third-spaces’ (places outside of home or an office) such as coffee shops appears to increase entrepreneurship and innovation.

In Chapter 3, Rubinstein presents two broad economic models of the world – one which is a ‘market-based’ economy model (commonly accepted by students of economics), and one of a ‘jungle’ economy (the strongest wins). The presentation of both models is done intentionally in a way to make them look similar, forcing the reader to notice the similarities between the two worlds. Moreover, this model is presented in the following paper – where Rubinstein and his co-author, Michele Piccione, wrote two separate conclusions!