When Free Trade isn’t Free

In his State of the Union address, President Biden underscored the need to “Buy American” – is this a good policy?

Summary

‘Free trade’ is being discussed again due to President Biden’s emphasis on ‘Buy American’.

‘Free trade’, in the context of removal of tariffs and quotas, has been shown to typically be good for the domestic economy and economists support it with near unanimity.

When attempting to define ‘free trade’, there are many issues relevant to how it is enacted.

Free Trade Agreements contain more that just tariffs and quotas, but also issues such as patent rights and differences in regulation.

In contexts where goods may appear similar, but actually are not, such as hormone-free and hormone-fed beef, ‘free trade’ may no longer be beneficial to a country.

Free Trade Agreements are a misnomer and should be viewed simply as agreements.

Introduction

On February 7, President Joe Biden made the annual State of the Union speech. One key phrase he mentioned stirred a lot of discussion on social media between economists:

“We’re also replacing poisonous lead pipes that go into 10 million homes and 400,000 schools and childcare centers, so every child in America can drink clean water. We’re making sure that every community has access to affordable, high-speed internet….And when we do these projects, we’re going to Buy American. Buy American has been the law of the land since 1933.1 But for too long, past administrations have found ways to get around it. Not anymore.”

This speech has been perceived as a focus on protectionist policies, keeping foreign goods and services out of the US. The reason this has stirred a lot of debate is that economic theory and practice is unanimous that such protectionist policies are detrimental to not only other countries, but also to US citizens. The issue, however, that arises is that although we all have a feeling about what ‘free trade’ means, what is it exactly and how is it implemented? These details are far more nuanced and alter how we perceive this concept.

Why Free Trade

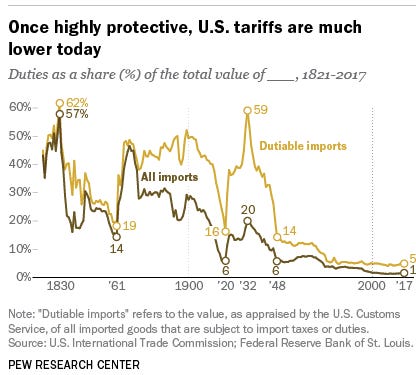

When discussing ‘free trade’, the concept we most often focus on is tariffs or quotas on imported goods. The world used to be very protectionist – in 1930, the US passed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, which increased tariffs on 20,000 imported goods. This trend was reversed after World War II, with a gradual reduction of tariffs and quotas. In 1947, 23 countries signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (“GATT”). Prior to 1947, the average tariff rate was around 22% (i.e. an additional 22% tax was levied on imported goods). Over the next several decades, the effective tariff rates were reduced, culminating in 1999 GATT negotiations that resulted in an average tariff rate of 5%. Today, the average tariff rate is in the 2 to 3% range.

Economists are nearly unanimous in the idea that ‘free trade’, in the context of removal of tariffs and quotas, is good and should be enacted. In this 2012 poll of economists, 35 out of 37 economists responded agree or strongly agree to the question “Freer trade improves productive efficiency and offers consumers better choices, and in the long run these gains are much larger than any effects on employment.”

The reason why trade is beneficial to societies is explained by a concept known as Comparative Advantage developed by renowned economist David Ricardo. Taking his example, suppose it takes England 100 hours of labor to produce cloth, and 120 hours to make wine. Suppose it takes Portugal 90 hours to make cloth and 80 hours to make wine. In order to enjoy 1 unit of cloth and 1 unit of wine, England needs 220 hours of labor, while Portugal needs 170 hours. In this example, Portugal is better at producing both goods than England, as they need fewer labor hours. However, with trade, both countries can do better. If England specialized in cloth production, they could produce 2.2 units of cloth for 220 hours. If Portugal specialized in wine, they could produce 2.125 units of wine in 170 hours. Using the same amount of labor hours as before, England and Portugal produced more than they did before – by trading 1 unit of cloth for 1 wine, England can now consume 1 unit of wine and 1.2 units of cloth for the same 220 hours of work, while Portugal can consume 1 unit of cloth and 1.125 units of wine for the same 170 hours of work. Trade has made both countries better off – same amount of work but more goods to consume.

It is worth noting, however, that although a country overall is better, it does not necessarily mean that everyone in the country is better off from opening up to trade. Recent research has started focusing on people that lose out from trade. Autor et (2013) found that opening up to trade from China had adverse effects on workers from impacted industries, especially manufacturing, with increased unemployment, reduction in earnings, and increase in disability uptake. The magnitude of these adverse changes depended on the level of import competition faced by these industries - the more an industry’s output could be replaced by imports from China, the worse it was for the workers in that industry. Langer (2020) found that opening up trade to China may have reduced lifetime consumption of manufacturing workers by 2.5% to 5%. Thus, although trade increases total consumption in a country, unless there are mechanisms that redistribute these gains to ensure everyone benefits from trade, there is potential for individuals in an economy to be worse off.

If ‘free trade’ can make everyone better off (conditional on redistributive mechanisms), why is ‘free trade’ not implemented everywhere and we keep hearing about protectionism? Unfortunately, ‘free trade’ is not a well-defined concept. The above discussion on ‘free trade’ only focuses on a very narrow concept of it – just tariffs and quotas. There are many other barriers to trade that are usually the focus of trade negotiations.

Free Trade Agreements – a Misnomer

Rodrik (2018) analyzed the state of policy and debate around ‘free trade’. To illustrate the difference between what economists typically have in mind when thinking about ‘free trade’ (tariffs, quotas) and what free trade agreements (“FTA”) actually are, he looked at two FTAs. The US-Israel FTA signed in 1985 consisted of 8,000 words and focused predominantly on tariffs, agricultural restrictions and import licensing. The US-Singapore FTA signed in 2004, contained 70,000 words. A large part of the agreement focused on issues such as “anti-competitive business conduct, electronic commerce, labor, the environment, investment rules, financial services, and intellectual property rights”. FTAs are clearly not just focusing on tariffs and quotas, as economists perceive them.

Rodrik (2018) elaborates on 4 key elements that recent FTAs have focused on: 1) rules and laws pertaining to patents and intellectual property (“IP”) rights protection; 2) rules around financial markets and capital flows; 3) a framework for legal disputes between foreign companies and host governments; and 4) harmonizing the different regulatory standards for goods and services between countries.

Issues 1 through 3 are important issues (briefly described in the Appendix), but the main focus in this article is issue 4. Regulatory standards are very important components of trade negotiations. These regulatory standards can be divided into two categories – some regulatory standards are designed intentionally to protect the country’s industry, while others are a reflection of the preferences of the people in the country. For example, the US and European Union (“EU”) failed to sign the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (“T-TIP”), mainly due to these regulatory discrepancies. The EU has significantly more stringent regulations around food safety, pesticide usage, and genetically modified organisms than the US. Beef produced in the US is hormone-fed, while European beef is not. Thus, these beef products are not the same. If the EU opened their markets to US hormone-fed beef, European beef producers would not be able to compete with US producers due to their higher costs of keeping beef hormone free. Since EU consumer groups advocated for hormone-free beef, European negotiators did not acquiesce to US demands to remove the restrictions on hormone-fed beef.

This creates a natural issue in the concept of ‘free trade’. Are such restrictions against ‘free trade’ (the US believes these restrictions are unreasonable and amount to protectionist policies) or are they a valid representation of a society’s preference? This is no longer a question about tariffs or quotas, but a far more nuanced discussion on what exactly is each good or service. If a country ends up with a beef product that is different than what they wanted, this could be seen as negative consequence of ‘free trade’. Beyond the specific type or quality of goods being traded, even how these goods are produced can be important. Labor and environmental standards differ between countries, resulting in different production costs. For example, if a good is produced using lenient safety standards, which reduces the production cost, should we allow its import if our safety standards are far stricter? This is both an economic and even moral question. All of these elements can be seen as a trade barrier – differing quality, labor, safety and environmental standards. These questions open up a different perception on what exactly is ‘free trade’, as just removing tariffs can come at a cost we never intended to occur.

One such issue is the potential for negative environmental impact. To give an anecdotal example, you can look at the US tuna fishing industry in San Diego. Throughout the 1900’s to 1960’s, San Diego was a large producer of canned tuna, even informally known as the ‘Tuna Capital of the World’. From the 1970’s new regulations around sustainable fishing were introduced to protect fish populations. This pushed out the whole tuna industry, and tuna fishing in San Diego collapsed, with very few fishermen remaining in the region today. However, demand for fish in the US did not subside. Today, approximately 90% of the 7.1bln pounds of consumed seafood per year is imported. A significant amount of these fish come from fisheries that have far less stringent sustainability standards than the US fisheries have. Tuna is heavily over-fished globally. The issue arising here is simple – tuna fished by San Diego fishermen was inherently different from tuna being imported. For simplicity, one was sustainable and therefore costly, while the other was unsustainable and cheap. By enacting ‘free trade’ (i.e. simply the removal of tariffs or quotas) without harmonizing regulations first, we arrived at an outcome, where instead of having sustainably harvested fish, we have made the problem of overfishing even worse. This situation is further exacerbated by fishing subsidies that encourage overfishing.2

Conclusion

The concept of ‘free trade’ is too vague to be meaningful. Trade agreements involve a lot of negotiation on issues that are beyond what we used to consider as ‘free trade’ – tariffs and quotas. The other components, especially regulatory issues, are just as important, not only for the negotiating countries, but even for the wider environment. But these tools are also manipulated by countries and special interest groups to create benefits for themselves. Economists should no longer be quick to say ‘free trade’ is good. Rodrik (2018) summarized it as follows:

“Trade agreements could still result in freer, mutually beneficial trade, through exchange of market access. They could result in the global upgrading of regulations and standards, for labor, say, or the environment. But they could also produce purely redistributive outcomes under the guise of “freer trade.” As trade agreements become less about tariffs and nontariff barriers at the border and more about domestic rules and regulations, economists might do well to worry more about the latter possibility. They may even adopt a stance of rebuttable prejudice against these new-type trade deals—a prejudice against these deals, which should be overturned only with demonstrable evidence of their benefits.”

Turning attention back to Joe Biden’s renewed focus on ‘Buy American’, depending on the context, this policy may be harmful or beneficial. Tariffs and quotas on goods that are highly similar and produced under similar regulatory conditions, are highly inefficient for overall economic output and will hurt the US consumer. However, in instances where the goods differ in the above qualities (method of production and production laws), such as the tuna fishing example above, ‘free trade’ might no longer be the optimal outcome. Depending on how it is implemented, ‘Buy American’ and other protectionist policies in other countries might reduce or improve outcomes for local citizens.

Appendix

Regarding the main concerns around issue 1 through 3 (for simplicity, I address one country as ‘domestic’ country, while the other country as a ‘foreign’ country):

Issue 1 – Rules pertaining to patent and IP rights: Patent and Intellectual Property rights protection are needed for domestic companies to be willing to transfer their goods and services abroad. Their concern is that they may lose claim to their patents and IP in foreign jurisdictions. However, some of the Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are very restrictive, allowing the patent holders to have a full monopoly in foreign countries. This results in a significant wealth transfer from poorer (foreign countries that have to pay high prices for patented goods) to richer countries (domestic countries that usually have the patent or IP).

Issue 2 – Rules around capital flows: Domestic companies want to be guaranteed that they can access the money they receive abroad or the capital they invest abroad. However, if the economic situation in a foreign country worsens, then if domestic companies withdraw their capital, this could further escalate the economic crisis. To prevent this situation, capital controls are needed. This tool, capital controls, is now seen as a relevant government tool for economic stability.

Issue 3 – Rules around legal disputes between foreign companies and governments: This is the most controversial issue, as it allows domestic companies to settle disputes with foreign countries using external legal frameworks, such as arbitration tribunals (an agreed upon third party that will settle disputes). Under such arrangements, domestic companies can potentially question any changes in a foreign countries’ laws that might adversely impact the domestic company. Furthermore, settling these disputes is not conducted under the laws governing the foreign country, but under the rules of the FTA.

The Buy American Act of 1933 required the US government to purchase US-made products whenever possible. It can be waived in the context of trade agreements with other countries or institutions such as the World Trade Organization.

More broadly, the question of the impact of ‘free trade’ on the environment was discussed using a theoretical approach by Antweiler et al. (2001). They focused on two effects: the scale effect and technique effect. The scale effect refers to the fact that due to higher economic output caused by ‘free trade’, we produce more pollution. The technique effect refers to the fact that as we become richer (due to ‘free trade’), we focus on more environmentally friendly technologies. They found that the technique effect outweighed the scale effect and thus, ‘free trade’ reduced pollution. The one caveat on this study is that it is now dated.