More than a Safety Net – Value Created by Unemployment Benefits

Welfare programs, like unemployment insurance, are rarely mentioned as policies that are positive-sum.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

If you would like to support us in reaching our subscriber goal of 10,000 subscribers, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

Zero-sum thinking occurs when a person believes that an outcome from a particular interaction, especially an economic one, results in one person benefiting at the expense of another. This concept contrasts with positive-sum thinking, where interactions can create mutual benefits, adding value for all involved. Media outlets have recently covered this zero-sum phenomenon as it appears younger generations are more likely to perceive issues using the zero-sum framework. One common topic that is often viewed as zero-sum is immigration, where many believe locals are worse off when immigrants come, even though research, almost universally, shows immigration is positive-sum.

But another issue is also often viewed by many as zero-sum – unemployment insurance.

Unemployment Insurance – Value Creating

Unemployment insurance (“UI”) – a program that provides financial support to individuals who have lost their jobs and are actively seeking new employment – is viewed by many as an ‘unfair’ redistribution from those who work to those who aren’t working. After all, why should we pay people to not work? This is clearly a zero-sum situation. Or is it?

Theory of Unemployment Insurance

The purpose of UI is to smooth transition for workers between jobs. Getting laid off reduces income, which significantly affects individuals. UI aims to mitigate some of the financial strain by providing a portion of the lost income, called the replacement rate, while the newly unemployed person looks for a job.

A common concern of UI is the ‘moral hazard’ issue, where an unemployed person may prefer to collect UI rather than look for a job. Since claiming UI is usually limited to a specific amount of time (for example, in the US it is typically around 26 weeks, whereas in Denmark it can be up to 2 years), the concern is that the unemployed may delay finding a job or accepting a job offer.

However, one commonly overlooked aspect of UI is that it allows the unemployed person to seek out better job matches rather than hastily accepting any job. UI helps an unemployed person meet their needs, which gives them a level of security that allows them to look for jobs that better match their skills and wants.

UI Recipients vs non-UI Recipients

McQuillan and Moore (2025) (“MM”) looked at how receiving UI impacts job outcomes for UI recipients. Typically, research has looked at how the size of UI benefits (the replacement rate or duration of UI) rather than the mere act of receiving any UI, impacts job outcomes.

MM looked at the UI program in Washington state due to its unique feature – UI eligibility is based on the number of hours worked (680 hours) and not the amount earned, which is commonly the condition in other states. This unique hours-based eligibility means that Washington state collects data on the number of hours worked by workers, which will be an important source of data in evaluating the impacts of UI receipt.

To evaluate the impact of UI receipt, MM looked at workers who just crossed the eligibility threshold (i.e. worked just about 680 hours or 17 full time weeks) to claim UI and compared them to workers that did not reach the threshold and could not claim UI. Furthermore, MM focused on workers that found a job within 5 quarters after becoming unemployed. This is done to focus on workers that have experienced job loss rather than individuals that are exiting the labor market (if a person has to leave the labor force to take care of someone, it would not make sense to study whether receiving or not receiving UI impacts their future job).

Who Are The UI Recipients

The sample of unemployed workers selected by MM had the following characteristics:

They typically earned around $11,000 (vs $61,000 for full time workers) in the year prior to becoming unemployed;

Average wage was $19 per hour (vs $28 per hour for full time workers);

The workers are typically in industries such as agriculture, fishing, retail, administrative support and hospitality.

Given these characteristics, as well as the fact that they have worked around 680 hours (approximately 17 full time weeks) in the year prior to unemployment, these workers were considered to be ‘marginally attached’ to the labor force.

Determining the Impact of UI Receipt

To establish what is the impact of receiving UI, MM compared workers who narrowly met Washington state's 680-hour UI eligibility threshold to those who did not. This quasi-experimental approach assumes that individuals on either side of the threshold are otherwise comparable – allowing any differences in outcomes to be attributed to UI receipt itself.

Results

MM first looked at what impact does UI receipt have on the duration of unemployment. Theory would predict that receiving UI should delay finding a job. MM’s results did not find any statistically significant change in finding a job in the same quarter the person is laid off, if they receive UI or not. The estimate itself is negative (suggesting people with UI do take longer to find a job), but the delay would not be longer than 1 quarter before finding a job.

More importantly, MM found that the unemployed that received UI, worked approximately 600 hours (15 weeks) more at their next job than those who did not receive the UI benefit. This represents a 37% increase in the hours worked. Moreover, those that received UI, earned almost $15,000 extra in the next two years vs those who did not receive UI.

Better Job Match

The main reason behind these improved outcomes for UI recipients appears to be driven by the fact that UI recipients match with a better employer. To confirm this hypothesis, MM found that UI recipients had 1.6 fewer employers in the two years after their initial job loss, indicating greater job stability. UI recipients were also more likely to find full-time jobs rather than part time jobs.

Moreover, MM found that the jobs UI recipients got paid $3.32 per hour more, which was an 18% increase over the wages of non-UI recipients. Altogether, UI receipt appears to enable workers to find more stable, better-paying jobs where they are less likely to be laid off and less likely to quit themselves.

Evaluating Societal Returns

The above findings clearly demonstrated that workers benefit from UI receipt. But does it make financial sense for society to pay these UI benefits? The answer is yes.

An average UI beneficiary in the study receives around $4,000 in UI benefits. In exchange, the UI beneficiary generates around $15,000 more in income over the next two years than non-recipients. MM also point out that from a welfare perspective it is worth splitting up the extra income earned by the UI beneficiary, into income earned from working more hours vs income earned by having a higher per hour pay.1 If we keep the number of working hours constant between UI recipients and those who do not receive UI, the former earn roughly $5,400 more, which is again greater than the cost of the UI benefits.

In terms of marginal value, MM estimate that $1 extra of UI generates around $2.57 of extra value. Thus, according to MM expanding UI eligibility can be seen as one of the most cost effective policies.

Breaking Out of Zero Sum Thinking

The MM paper illustrates how UI benefits generate net value for society, making them a clear positive-sum intervention. Rather than simple redistribution, UI expands economic output by enabling better job matches and greater stability. Given this, expanding UI eligibility would be a socially optimal move.

Yet in the US, eligibility for UI is quite low and dropped after the Covid pandemic. Public discourse too often frames such transfers as “unfair” or indulgent welfare, rooted in a zero-sum logic. Economics, however, tells a different story: these are value-creating investments.

This perspective extends beyond UI. Programs like child tax credits and SNAP (food assistance) should likewise be recognized as investments in human capital rather than a consumption transfer. When governments spend money on infrastructure, it is rightfully seen as an investment. A similar approach should be applied to social benefits.

Interesting Reads from the Week

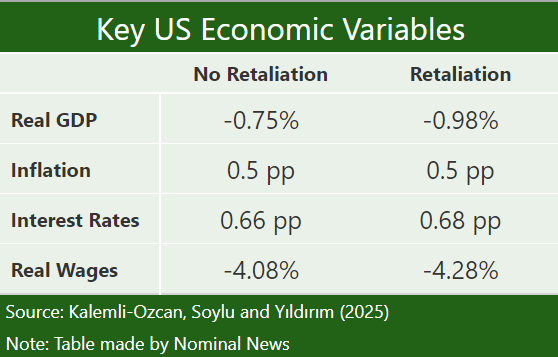

Paper Update: One of the papers we’ve discussed before has updated their model for the end of June US tariff policy. Whether other countries retaliate or don’t, the adverse on impact on US workers will be large – a 4% fall in real wages.

Article: Thomas L. Hutcheson goes over some of the considerations the Federal Reserve may be considering in the debate about whether to cut interest rates.

Article: Hayden Clarkin goes over the ways street design and road solutions aim to discourage drivers from speeding without explicitly telling them to slow down.

One could argue that having to work more hours is not necessarily welfare improving, since the worker now has less leisure time.

I do not dispute that UI can have efficiency effects, but I see no harm in advocating for it as a pure consumption transfer from the employed to the unemployed any more than is the transfer from the insured whose houses did not burn down to the insured whose houses did.

"Breaking Out of Zero Sum Thinking

The MM paper illustrates how UI benefits generate net value for society, making them a clear positive-sum intervention. Rather than simple redistribution, UI expands economic output by enabling better job matches and greater stability. Given this, expanding UI eligibility would be a socially optimal move."

Perhaps there is some truth to that line, somewhere, but certainly not where I come from. It is a straight up redistribution scheme that foments dependency on others, namely the taxpayer, and poverty. Every cent taken from the 80% of folks who make up this country to support State provided UI is an insult to the working classes and the notion of self reliance and individual sovereignty that built this country.

I might have bought into the premise had the concept of self insurance come up even once. Folks that work for a living are familiar with the concept if they are self insured for long term disability. That works and is totally funded by worker voluntary participation; not like involuntary seizure as in State provided UI or Workers' Compensation.

I believe there is no way a cost:benefit analysis model could have come up with that conclusion sans some serious manipulation of both real economic cost:benefit or social benefit:cost data and most likely, the variables. It does not compute in a real world long term analysis any more than GMI does.

I do not dispute the short term value to the those unemployed because of disability or their employer's economic circumstances, but I will not voluntarily support those terminated for cause, nor should any other American citizen. We, as Americans, are morally bound to care for those among us who cannot realistically care for themselves but also morally bound to demand self reliance and positive contribution to our society by those so capable and reasonably able.