Electoral Issue #4: Minimum Wages

Minimum wage laws have been criticized on theoretical grounds that they reduce employment. But research suggests otherwise.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

We are almost at our 1,000 subscriber goal:

If you would like to support us with reaching our goal, please consider sharing and liking this article!

With the US presidential elections coming up in November, several issues have come to the forefront. Over the next couple of months, we will focus on what economic research has to say about these issues. We will not be focusing on or assessing specific policy proposals, but rather on what the economic literature can contribute to our understanding of the issues. Although the inspiration for these articles is the US election, these issues are broad enough to impact many countries.

Minimum wage laws, which is the lowest remuneration a worker can legally be paid, are a very contentious topic in economics. That is because economic theory suggests that such laws can have serious distortive effects on the labor market. Minimum wages may reduce employment in two ways:

fewer workers may be hired (this is referred to as the extensive margin impact); and

each worker may end up working fewer hours due to the higher cost (referred to as the intensive margin).

However, minimum wages also strengthen the wage bargaining position of workers, giving workers a higher wage floor.

Naturally, the overall impact of minimum wage laws can be tested by looking at data.

I. German Minimum Wage Laws

Germany is an interesting case for studying minimum wage laws. Historically, due to the high unionization rate, Germany did not have an economy-wide minimum wage. However, in 2015, Germany introduced a minimum wage at EUR 8.50. The minimum wage grew with inflation until about 2021 to EUR 9.82. When a new government was formed in 2022, the minimum wage was increased above the inflation rate, first up to EUR 10.45, then to EUR 12.00. This 22% increase in minimum wage was substantial and impacted around 4.4 mln workers in Germany.

Bossler, Chittka and Schank (2024) studied this change in the minimum wage to see how it impacted the German economy. Bossler, Chittka and Schank used a newly created Earnings Survey in Germany that asked establishments for specific data on the employee’s wages and hours worked. If an establishment was selected, participation in the survey was mandated by law. The Earnings Survey collected data on 58,000 establishments, covering 8mln employees, every month from January to December 2022. The survey itself was actually created for the purpose of understanding the impacts of minimum wage laws.

Bossler, Chittka and Schank found that after the second minimum wage increase (from EUR to 10.45 to EUR 12.00), average wages of the people who were earning less than EUR 12 went up by 6%. Moreover, there was no noticeable reduction in employment. There was however a slight reduction in hours worked – impacted individuals worked 1% fewer hours, meaning their overall monthly wages went up only by 5% on average. Thus, it appears that a significant minimum wage change had a net positive impact on workers with minimal downsides.1

II. California Wages – Fast Food Industry

From April 1, 2024, all employees in California’s fast-food and bar industry (with a few exceptions) had to be paid at least $20 per hour. This is one of the highest minimum wages in the US and impacted around 750,000 workers, as 90% of non-managerial fast-food workers in California earned less than $20.

Using Glassdoor data (a job posting website), Reich and Sosinskiy (2024) found that wages for fast food workers prior to the implementation of the new policy were approximately $17 per hour. After the start of the policy, wages jumped to the $20 minimum wage. Separately, in other states, where there was no change in minimum wage, fast food worker’s wages did not change.

Reich and Sosinskiy also looked at establishment level survey data (similar in nature to the German data above) and found that employment in the fast food industry in California has continued to rise. It is worth noting that this is not direct evidence that the minimum wage did not affect employment – absent the change in minimum wage laws, maybe employment would have grown faster. Lastly, Reich and Sosinskiy did not study if the number of hours workers worked changed due to insufficient data.

Who Pays?

One additional question many typically ask about changes in minimum wage laws is how does this change impact prices of the goods sold (the informal question of ‘who pays for the increase in minimum wage’). Reich and Sosinskiy looked at the price of burgers at fast food places in California and found that after the enactment, prices for burgers went up by 3.7% relative to other states, where such a policy was not enacted. Since approximately 30% of the costs in a fast food business are labor costs, a full pass through of the minimum wage increase should have resulted in a 6% increase in prices (18% wage increase times 30% of cost = 6%). This means that the minimum wage pass through was only 62% (3.7/6).

Since prices did not absorb the full increase in labor costs, the businesses themselves most likely ended up with lower profits. However, another reason why prices did not rise to fully offset the cost increase could be due to the reduction in worker quits (less severance pay and more skilled employees retained), and the associated reduction in the need to hire workers (lower training costs and hiring bonuses).

III. Brazil – Spillover Effects of Minimum Wage Increases

Engbom and Moser (2021) studied one more avenue that minimum wages may impact the economy – wage inequality. From 1996 to 2012, Brazil experienced a significant reduction in wage inequality. As can be seen in the figure below, the distribution of wages (here measured in multiples of the minimum wage after taking the logarithm) significantly bunched up (Panel A is 1996, while Panel B is 2012). Moreover, this wage compression was driven by workers in the lower end of the distribution. Panel C shows, in blue, that the ratio between the 50th percentile earner and the 10th percentile earner fell significantly, while the red line shows the ratio of the 90th percentile to the 50th percentile earner.

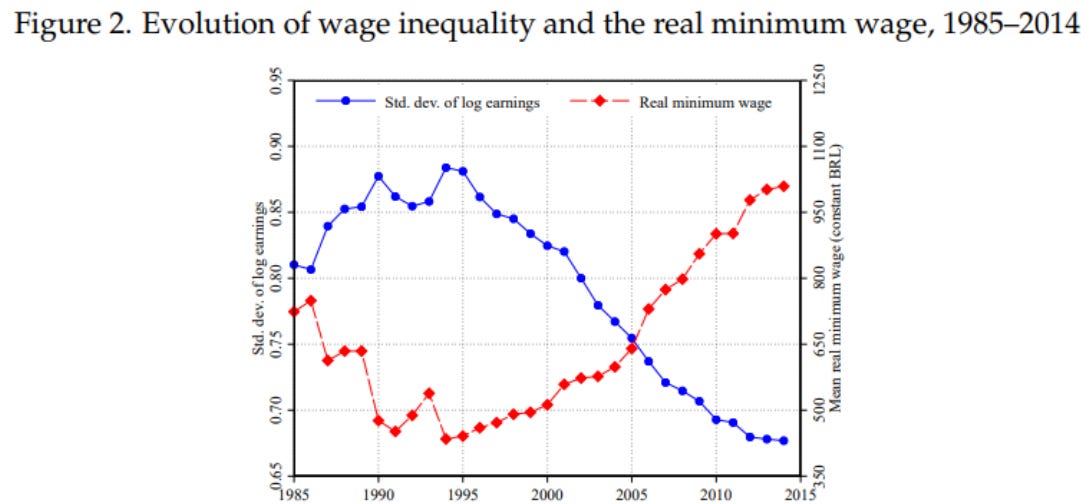

From 1996 to 2012, the Brazilian minimum wage was increased in real terms by 119%.2 In 1996, the minimum wage was at the level of 36% of the median wage, while by 2012, it was at 60% of the median wage. The standard deviation of earnings (the level of dispersion in wages – higher dispersion implies higher inequality) during this time fell. Below is a figure showing the evolution of the real minimum wage and the standard deviation of earnings:

Although the above chart may suggest that the minimum wage increase effectively reduced inequality, this is only a correlation. To determine causality, Enbgom and Moser used the fact that the minimum wage had different levels of ‘bindingness’ in different Brazilian states. That is, in states where there were more low earners, the minimum wage, which was set at the national level, would be binding on more workers than in states that had more high earners.

Engbom and Moser found that the Brazilian minimum wage increases impact not only workers earning below the minimum wage, but even workers in the 90th percentile of the income distribution. Overall, over half the observed fall in inequality can be explained by the increase in minimum wages. Moreover, Engbom and Moser did not find any effects of increasing minimum wages on average hours worked nor employment levels. The authors did find that smaller firms did exit the market, with more larger firms staying. This is a typical finding in economics – larger firms became larger because they were productive. Thus, once minimum wages are increased, large firms are able to keep workers and generate profits, while small firms lose out.

Explaining This Pattern

The above discussion focused on data. To be able to explain why the data ‘behaved’ the way it did, Engbom and Moser turned to a model of the economy. The main reason for the fall in inequality is driven by the fact that wages for identical workers (but at different firms) became similar. This is especially true for low earners/low productivity workers. By increasing the minimum wages, low productivity firms could no longer offer low wages. This resulted in either the low productivity firms increasing the wages for these workers or the low productivity firms had to shut-down.

The closure of low productivity firms also works out as a positive for two reasons: it is easier for workers to now find the higher productivity firms (since there are fewer low productivity firms) and it is easier/cheaper for high productivity firms to hire employees since there are fewer firms competing for workers. Interestingly, under higher minimum wages, Engbom and Moser found that high productivity firms actually increase hiring intensity because the payoff is now greater (the firm is more likely to be successful in finding workers).

Overall, Engbom and Moser found, in their model, that increasing minimum wages results in lower inequality with limited to no impact on employment. Total output increases in the economy as there are more workers at high productivity firms. It is worth adding a caveat – Engbom and Moser noted that similar research on other economies (US, Canada, UK) did not find such large inequality impacts of increasing minimum wages as the impact in Brazil. Engbom and Moser believe this is due to the current skill distribution – the US, Canada and the UK have significantly more highly-trained workers, and thus minimum wages do not impact these workers as much. In Brazil, on the other hand, the majority of workers are not as trained, and many more workers start off their careers at the minimum wage, which is not a typical pattern found in developed economies.

IV. Minimum Wages – an Economic Tool

Based on the above latest research, it appears that increasing minimum wages can have significant positive effects with limited negative outcomes. If we think of minimum wages as a method of weeding out ‘bad’ firms, this result is not surprising. Similarly to ‘cheap’ capital (low interest rates), ‘cheap’ labor can keep unproductive firms in business because these businesses can survive by offering low wages rather than offering a product or service efficiently. The existence of these inefficient firms can actually be harmful to the economy as it siphons away resources, capital and labor, from the productive firms. Thus, it may not come as a surprise that the effect on unemployment of minimum wage laws seems muted.

Lastly, none of these studies looked at what is the optimal minimum wage. It wouldn’t be surprising that a high minimum wage may be counterproductive. However, research clearly shows that there is a space for a positive minimum wage as it can both reduce inequality and improve economic efficiency.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Atif Mian discusses why certain foreign investments might not be beneficial to the country receiving the foreign investment. Good foreign investments may need to be paired with technology and “know-how” transfers.

Article: Erman Misirlisoy, PhD talks about a study that found that “people's identities converge after brief discussions”. Turns out that having conversations with others may align our personal traits with the average of a group.

Article: Dr. Andrea Love tackles the issue of selective science acceptance/rejection in the context of health and wellness, particularly around food. I see some comparisons in the economics field – some economists tend to go with their beliefs about certain topics, rather than look at the research on the topic.

The Electoral Issue Series:

Electoral Issue #1: Investing in the Future – Child Tax Credit

Electoral Issue #2: Why We Demand Bad Policy

Electoral Issue #3: Immigration

Electoral Issue #4: Minimum Wages

Electoral Issue #5: Tariffs, Tariffs…

It is worth noting that these results are derived by comparing what happened to employees earning less than EUR 12, to employees that were always earning more than EUR 12. This is the appropriate comparison. If there was a significant increase in wages for employees that were earning more than EUR 12, then the increase in wages for employees earning less than EUR 12 could be driven by an economy-wide factor – i.e. it would have happened regardless of the change in minimum wage laws.

Real terms means we are accounting for inflation.

Interesting article and thank you for the shout-out!

There are lots of rationales for minimum wages, but fundamentally I think it is t raise the incomes of low-wage workers. The sophisticated arguments are basically about the (often quite low) cost of the transfer. Consequently it makes a lot more sense to just raise the EITC.