Marriage Preferences and Gender Outcomes

With the onset of spring, come weddings – how does partner preference impact behavior and long-run career outcome?

For next week, we will write on a topic requested by one of our subscribers. If you have a topic you are interested in, please feel free to share it in the comments below! Additionally, below is a poll about the posting time of these articles. We have typically been posting on Sunday evening Eastern Time. Please let us know if you think another time would be better! Thanks! - Nominal News Team.

Introduction

As a few of our friends have gotten engaged recently, this has inspired us to discuss the topic of marriage and what are some things economics has to say about it. Marital choice and partner selection are rich social interactions for economists to study as they involve many economic theory based behaviors. For example, there is asymmetric information, where each potential partner has information about themselves that the other person does not know. There is also signaling, in which an individual intends to convey unobservable information to a potential partner. In a marriage, there are many decisions needed to be made by spouses regarding both selfish (i.e. personal) interests and communal interests, such as chores. Some form of implicit or explicit negotiation occurs, even if it does not seem like it to us.

There are many angles economics researchers have looked at the various questions around marriage – modeling how we find a partner, the differing costs of marriage and finding partners by a variety of observables (gender and earnings), and how marriage has impacted the wider macroeconomy. In this post, we will discuss how partner selection differs by gender and affects career outcomes of women.

Partner Selection – Gender Differences

First, we will look at the question of partner selection. As we anecdotally know and feel, men and women approach partner selection differently. However, even though it might seem obvious, that question can and should be addressed in a systematic way. However, it is usually difficult to get truthful responses from individuals just by asking them, especially on a potentially sensitive topic such as dating preferences. Thus, it is important to use a research method such that individuals will truthfully report their preferences. One such way is through setting up a field experiment.1

Fisman et al. (2006) conducted such a field experiment experiment in order to infer people’s preferences by hosting real speed-dating2 events. During these events, participants would record after each round whether they would like to see each other again. If a match did occur, contact information would be exchanged, thus participants had an incentive to be truthful. What Fisman et al. found is that women put more emphasis on intelligence and race, while men put more emphasis on attractiveness. Moreover, the men preferred women who are less intelligent and, especially, less ambitious than them. These field experiment findings on ambition are consistent with what is referred to as the ‘social structure theory’. This theory posits that social arrangements and societal roles are more important in determining individuals’ particular decisions rather than biological reasons.

So why are economists concerned about these partner preferences – after all, they may simply be individual choices that have little bearing on others? The old economic adage is that individuals respond to incentives. This implies that simply knowing about other people’s preferences might alter your own behavior. As it turns out, further economic studies have shown this to be the case.

Real Costs of Preferences

Bursztyn, Fujiwara and Pallais (2017) conducted a field experiment on newly admitted MBA students. The authors used a survey to ask students certain career and personality questions. As with all survey-type studies, there is an issue of whether respondents will give truthful answers. We covered an example of how survey design was important to elucidating honest responses when we discussed gift giving. However, in this instance, the MBA surveys were perceived by the surveyed, as something more than just a meaningless questionnaire. As this was a newly joining MBA cohort, this was the first time they would be offering their information and preferences to the career center. The career center does use this information to set up internships – individuals that aren’t willing to travel as much, would be steered away from consulting, while people that prefer shorter hours, would be less likely to get internships with investment banks.

Bursztyn, Fujiwara and Pallais conducted the surveys and randomly told some of the students that their results will be shared publicly with other students, while others were told their answers would remain private or anonymous. The results of this study were illuminating. Single women who believed their answers may be made public in front of their classmates, desired $19,000 lower annual salary ($112,000 vs $131,000), desired less work travel per month (6.6 days vs 13.5 days) and were willing to work fewer hours per week (48.3 hours vs 52.2 hours) than if they believed their answers would be anonymous! The same pattern was found for specific personality traits – single women were less likely to want to lead or state they were ambitious if their information would be shared in a public setting.

Confirming Causality

The above experiment might not be sufficient to determine whether men’s preferences might be causing single women to act differently. Theoretically, there could be an unobserved variable that could make it more likely for women to both be single and alter their response if it would be presented in a public setting.

To address that issue, Bursztyn, Fujiwara and Pallais performed additional experiments and analysis. The authors conducted an experiment during which students, in smaller groups, were asked to rank which type of jobs they would prefer (higher salary and longer hours vs lower salary and shorter hours) and told that their responses may be discussed at the end of the session. When placed in all female groups, women are far more likely to choose jobs with higher salaries and longer hours, as well as jobs with faster promotion schedules but included more travel. Women were more likely to prefer lower salary outcomes in groups in which there were more single men as opposed to married men. This difference in response leads more credence to the idea that it is social expectations influencing behavior of single women.

The authors also noted that single women tended to have lower class participation grades than married women. In a class setting, their participation would be seen by others. However, their performance on midterms, final exams and problems was similar to married women, suggesting that skills and ability are not an explanatory factor.

An additional survey asked students about their experiences. Bursztyn, Fujiwara and Pallais. found that 64% of single women avoided asking for raises or promotions to avoid looking “too ambitious, assertive, or pushy”. Only 39% of women who were married or in a serious relationship and 27% of men said the same. Similarly, single women tended to avoid speaking up in meetings to avoid looking too ambitious. All of these results may also be somewhat downward biased,3 as people pursuing an MBA are more likely to be more focused on career enhancement and getting a higher salary.

These results demonstrate that the preferences of men for less ambitious women has real impacts on women’s decisions and behaviors. Whether consciously or subconsciously, evidence suggests that women alter their behavior to appear more ‘attractive’ to potential partners. What are the ways we can deal with this situation? One solution that can work in the near-term proposed by Bursztyn et al. is to encourage schools and workplaces to make certain actions less observable. As the studies have shown, single women mainly alter their decisions when it would be observable to others. Thus, removing this channel would potentially prevent this behavioral adjustment.

Ambitious Women and Divorce

The Bursztyn, Fujiwara and Pallais study, given that there were lower stakes at play, might still be seen with a dose of skepticism. To determine whether women’s ambition could impact marital outcomes, a more direct study would be preferable. Folke and Rickne (2020), using an extremely rich Swedish data set, were able to study the impact of promotions on divorce rates. Folke and Rickne have 30 years of data and are able to track individuals that are applying to be promoted to become a mayor or a parliamentarian, which are both seen as very high positions (both from a reputational and financial perspective) in Swedish society.

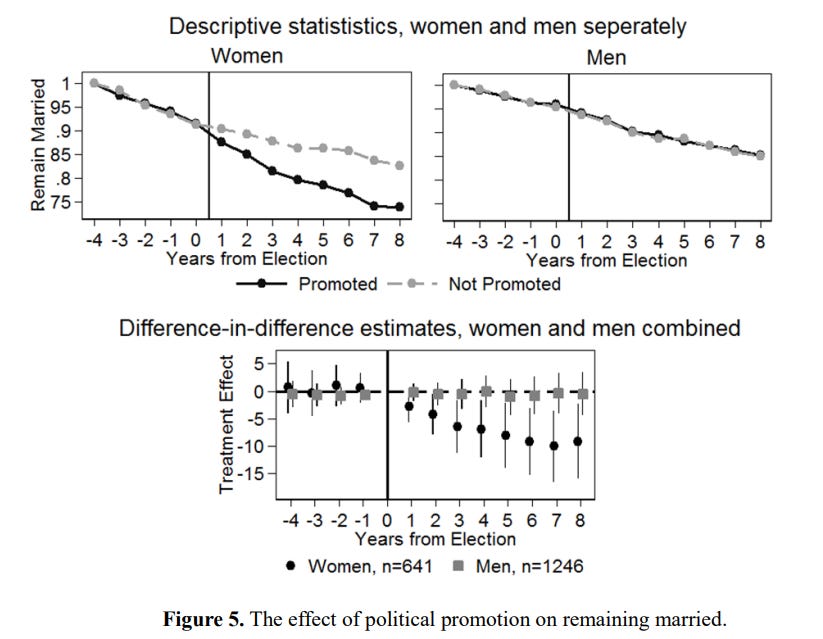

Firstly, Folke and Rickne find that divorce rates for promoted women go up, while there is no change for promoted men. Secondly, women that were promoted are twice as likely to get divorced than women that attempted, but failed to gain promotion. Folke and Rickne are also able to track pre-promotion data and thus, are able to rule out any differences between the women who got promoted or failed to get promoted, prior to the promotion.This pattern did not only hold in political roles – undertaking the same analysis on CEO promotions, the study found very similar results. The figures below visualizes the impact for political roles. As can be seen, in the 4 years prior to the election, women that would be promoted and women that failed to get promoted remain married at the same rates. After promotion, the marriage rate of promoted women drops by more than for women that failed to get promoted. No such effect can be seen for men.

The rich dataset allowed Folke and Rickne to analyze which types of couples were more likely to divorce. They found that gender-traditional couples, where there was a larger spousal age-gap and more gender-skewed division of parental leave,4 were more likely to divorce after the promotion. Women in more gender-equal marriages did not divorce more often after a promotion. Folke and Rickne highlight the issue between couple formation and the glass ceiling for women in the labor market. High ability men are often in relationships where the focus is on the men’s career, while high ability women tend to be in dual-earner relationships where the woman is primary care-giver. Women in traditional marriages find it tougher to get higher responsibility jobs due to the adjustment costs within the marriage, which includes task renegotiation within the couple.

Addressing the Issue – Long-Run

The above research describes the current social and economic situation. In economics, this is called ‘positive’ economics, which is describing the world as it is currently. The issue that arises is that given that men today prefer less ambitious women, women may find it rational to act in a less ambitious way in order to find a spouse, if that is their goal. This behavior, although logical currently, is clearly costly for women in the future.

One could, therefore, argue that, in order to improve outcomes for women and the economy in general, the perspective of men on women’s ambitions should be changed. This is referred to as ‘normative’ economics – i.e. what the economy ought to be. Resolving the perception by men of women in the workplace, which is a cultural phenomenon, is not an easy question – the most likely solution is a long-run one. Economists have also studied what can lead to cultural change in the long run.

Fernandez et al. (2004) assess one cultural component that may be important in forming men’s attitudes towards working women – working mothers. Throughout history, Fernandez et al. point out how several changes impacted women in the labor force – consumer durables (most famously, the washing machine) that made housework easier, the ‘pill’ that enabled women to control their fertility, leading to controlling their career, and the growth of service sector ‘white-collar’ jobs. All of these changes had a dramatic impact on women’s participation in the labor force, changing the entire cultural perspective around women in the workforce. Regarding more recent times, Fernandez et al. argue both theoretically and empirically, that growing up with a working mother has changed men’s attitudes toward working women. They found that having a working mother increases the probability of the man having a working wife by 24 to 32 percentage points.

Conclusion

Finding a spouse clearly impacts men and women very differently. The preferences of men and women also unequally affect the genders. This results in real costs for women as both their careers and earnings potentially suffer. There may be ways to mitigate some of these effects such as by anonymizing participants or obscuring certain actions in the workplace to reduce observability. However, any such stopgaps will not address the key long-run issue. Career decisions will always be publicly visible, so in order to enable women to reach their career goals and not having to worry about the implications it may have on their marital life, the perception of womens’ ambitions and desirability must change. That is a process that takes generations.

Finally, the above research has shown several important ways to assess the validity of studies which use survey data. When using survey data, it is critical to create incentives that will elucidate truthful responses. Surveys and social experiments in laboratories can typically suffer from incorrect data. If accessible, however, studies that use officially recorded data, such as the Folke and Rickne Swedish study of political candidates, will typically be better in establishing causality. This is due to the fact that the data they used was unlikely to be erroneous or suffer from any significant biases.5

If you enjoyed this post, please share it!

A field experiment is a research method that uses certain elements, such as randomization, of a typical laboratory experiment, but is conducted in natural or real world settings.

Speed-dating is an event whereby a group of people match in pairs for a short, specified amount of time (usually 5 minutes) to get to know each other. After the allotted time, they move on to the next person.

In econometrics, a biased result means that instead of capturing the actual impact of a particular variable, we are capturing a higher or lower value for a particular reason. In this instance, Bursztyn et al. are studying what is the impact of gender on ambition. A downward bias means that the true effect of being a woman on ambition would be higher (i.e. a randomly chosen woman would hide her ambition even more than these results imply). The reason for this is that people who pursue an MBA are likely to be more ambitious in the first place. This is called ‘selection bias’. Focusing on women who are likely to be more ambitious may ‘bias’ our results, as not all women in society have the same ambition levels as women that pursue an MBA degree.

In Sweden, parents get a total allocation of 480 days of parental leave, which can be divided in any way among the spouses. In gender-traditional couples, women take a significantly larger share of parental leave than men do.

For example, parental leave in Sweden requires applying to the authorities to receive payment. This entails formally declaring how many days each spouse is taking and is recorded by the authorities. If this question was asked in a survey - how many days of parental leave did you take - the provided data could be erroneous due to forgetfulness or potentially trying to give an answer that seems ‘better’.

Please can you write about if there is increasing market concentration and less competition due to corporate power and the impact this is having on people's economic state? for example this study https://mendoza.nd.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/2017_fall_seminar_series_gustavo_grullon_paper.pdf

So, if you want to keep your wife, sabotage her career :D