Immigration – Fiscal and Macro Impacts

Surveys suggest people think immigrants are a net negative on the budget. Research shows otherwise.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 3,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

We have been blown away by our growth this past month and are now updating our goal for 2025 to hit 10,000 subscribers!

If you would like to support us further with reaching our subscriber goal, please consider sharing and liking this article!

To finish off our recent article series on the impacts of immigration (the impacts of college-educated immigrants and non-college educated immigrants on the economy), let’s turn to the macroeconomic and fiscal impacts of immigration. A commonly held sentiment is that immigrants are fiscally costly. But, maybe unsurprisingly, research and evidence shows that this is not the case.

Fiscally Positive

Recent surveys by Gallup asked survey participants what they think is the impact of immigrants on taxes:

A plurality of Americans believe that immigrants make the fiscal situation in the country worse. But what’s the actual impact of immigrants on the fiscal health of a country?

Direct Fiscal Impacts

One factor to measure is the direct fiscal impact an immigrant has. The direct fiscal impact focuses on the payments into the government budget made by an immigrant (tax payments such as income taxes) and the benefits used and costs incurred by an immigrant (this includes education and healthcare costs, various transfer programs, incarceration costs and other public goods costs).

One of the most in-depth analyses has been performed by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) that looked at the impacts of immigrants on the US budget in 2017. The study looked at the lifetime fiscal impact of an immigrant. On average, the NAS finds immigrants are a net fiscal positive, but there’s large heterogeneity depending on the type of immigrant, especially the immigrant’s education level. For example, an immigrant with a college degree contributes on net $870,000 in today’s dollars into the budget throughout their lifetime. This significant benefit can be explained by the fact that college-educated individuals pay a high amount in taxes and do not need many benefits. For most education levels, the NAS estimates a positive or neutral fiscal impact (the effect can depend on certain technical assumptions).1 However, the NAS estimates that immigrants that have not completed high school, who only represent 20% of immigrants, cost $109,000. This estimate, however, is only looking at the ‘direct’ fiscal impact, while there may also be indirect fiscal impacts.

Indirect Fiscal Impact

Colas and Sachs (2024) looked at these indirect fiscal impacts of non-college educated immigrants.2 The term ‘indirect’ here refers to the fact that local workers are impacted by immigration and make different decisions due to immigrants. That is, local workers alter their decisions regarding whether to work and how much to work, when immigrants join the workforce. Colas and Sachs built a model of the economy where college and non-college educated workers are imperfect substitutes for production. Within each group, workers are perfect substitutes (i.e. there’s no difference between a non-college educated immigrant or local).

Colas and Sachs, using their model, found that non-college educated immigrants, which ‘compete’ with non-college educated local citizens, reduce wages and hours worked of non-college educated local workers, but increase the wages and hours worked of college educated local workers. Since the fiscal contribution of college educated workers is typically higher (higher tax rates and lower benefits usage), the indirect impact of non-college educated immigrants is positive and substantial. Colas and Sachs estimate that the indirect fiscal benefit of non-college educated immigrants is around $760 to $1,130 per year (depending on model assumptions). For reference, the median non-college educated immigrant pays around $2,600 in federal taxes annually, meaning the indirect impact is almost half of the federal tax revenue benefit.

It is worth noting that the Colas and Sachs estimates are model based3, as indirect effects can really only be estimated using a model. Naturally, the outcomes depend on the model assumptions. One thing the model does not consider (and the authors point it out too) is the indirect impact of immigrants on capital growth (i.e. more machines and technology). This is another positive impact of immigrants, as increased capital also increases tax revenues. Moreover, Colas and Sachs use a strong assumption of perfect substitution within an education level (i.e. non-college educated immigrants are perfect substitutes for non-college educated locals). Our recent article on non-college educated immigrants showed that this is not the case, as the employment of locals does not change in response to immigrants suggesting that immigrants are imperfect substitutes for locals. This would also increase the indirect effect, as we would not see a reduction in taxes from non-college educated citizens. Thus, in my opinion, the Colas and Sachs indirect benefits result appears to be a lower-bound.

Imposing Large Scale Immigration Restrictions

Beyond data-driven and model-based impacts of immigration, economists have also studied what happened when large immigration restrictions were imposed. Abramitzky, Ager, Boustan, Cohen and Hansen (2023) (“AABCH”) looked at what happened in the US after the implementation of much stricter immigration restriction in the 1920s. Prior to the 1920s, around a million immigrants from Europe arrived in the US each year. This was reduced to a cap of 150,000 immigrants.

As can be seen in the chart, the drop in the number of immigrants was large for migrants from southern and eastern Europe. In 1920, around 14% of the population was foreign-born, while by 1970, this percentage dropped to 5%.

The immigration policies of the 1920s imposed country-based quotas. They were most impactful on southern and eastern European migrants (Central Europe, Russia and Italy). Since immigrants would often settle in areas with more immigrants from their home country, the immigration quota system created a natural experiment.4 For example, an area in the US that had a significant Italian population would now have a significant reduction in immigrants, impacting local businesses and local workers. AABCH used this differential regional effect of immigration restriction, and looked at the impact on urban, rural and mining workers.

AABCH found that areas that saw a significant reduction in migrants saw no impact on earnings of US born workers. For US workers in urban areas, the impact to earnings may even have been negative. So what explains this fact?

Worker Movements

AABCH further investigated by looking at how labor flows and investment reacted to the immigration restrictions. In urban areas, where manufacturing was more present, any loss in new immigrants was offset predominantly by internal migration (from other US areas), and also partially by immigrants from non-quota impacted countries. Farmers, on the other hand, substituted for immigrant labor with more automation and mechanization (we discussed a similar outcome when Mexican immigration was reduced after World War 2 under the termination of the Bracero Agreement). In mining, however, where immigrants were a key source of labor, there was an industry contraction. No new workers replaced the immigrant worker flow and capital investment into new equipment actually fell.

This showed three different industry outcomes to immigration restrictions:

Urban manufacturing immigrant losses were offset by internal migration;

Farming immigrant losses were offset by capital investment;

Mining offset immigrant losses were not offset and the industry contracted.

Aside – Increasing Capital Investment

One of our readers left an interesting comment on our previous article regarding the increase in capital investment that offsets immigration restrictions in agriculture. As the commenter pointed out, this change can be viewed as potentially a positive one, as the country ends up having more capital and technological innovation in the agricultural sector. This is a good point, as innovation is generally assumed to be a positive.

However, this led me to a separate question – are farmers truly indifferent between using immigrant labor or technology? San (2023) looked at the termination of the Bracero Agreement – a World War 2 program that allowed Mexican immigrants to work on US farms. Annually, over 300,000 Mexican workers worked on US farms between 1942 and 1964. In 1964, the agreement was terminated.

As we discussed in our previous article, the termination of the Bracero Agreement did not result in higher wages or employment for domestic workers in the agricultural sector. San confirmed the result and found that crops that were more impacted by the immigration restriction (i.e. utilized more Mexican workers previously) saw a large increase in innovation and patenting, even 15 years after the termination of the program.

San also looked at what this change meant for farm owners. In theory, losing access to immigrant labor (or any labor) can reduce the profits of a farm, which would manifest itself as a lower farmland value (if a farm generates less profit, the land will be less valuable). However, improving farming technology and innovation would work in the opposite direction – increasing profits and increasing farmland value. San looked at how farmland values of US states that used Mexican workers developed over time:

Farmland values in states that had Mexican workers under the agreement dropped immediately after the termination of the Bracero Agreement and remained lower decades later. On the other hand, farms in states that didn’t use these workers saw no change in farmland value suggesting that the innovation was not sufficient to offset the negative labor impact. San concluded:

“...one can conclude that Bracero exclusion made capital worse off while making labor no better off”

Overall, it appears that from a farm owner perspective, the termination of the Bracero Agreement made them worse off.

Immigration – Economic Booster

Our three part series has shown that immigration does not seem to adversely impact locals. On the contrary, there are many positive impacts – increased job formation and increased wages, as well as improved state fiscal health. Immigration restrictions appear to only re-distribute domestic labor and capital without increasing returns (neither wages nor returns to capital increase). Moreover, immigration restrictions may result in the gradual, but accelerated, decline of industries, as was the case with mining.

In my opinion, the fact that immigration, especially in the US, has major positive impacts is not a surprising result. Intuitively, from an immigrant's perspective, the choice to immigrate is not an easy one. The individuals that choose to do so are already self-selecting into immigration meaning they probably have certain innate traits or characteristics that end up resulting in positive economic outcomes, regardless whether the immigrant is college educated or non-college educated.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Bruce Lesley discusses the private school voucher programs in the US (this program allows the use of public funds for private schools). These vouchers appear to both adversely impact public schools and not improve outcomes for users.

Article: Dr. Abdullah Al Bahrani shows the impacts of the 2018 steel and washing machine tariffs had in the US. In both cases, they were negative.

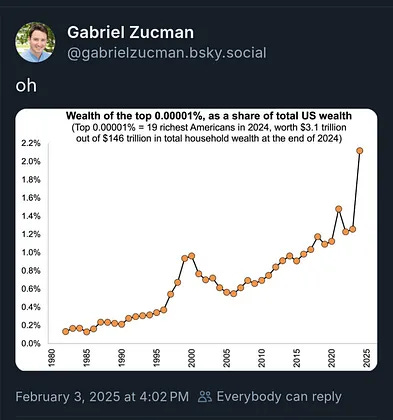

Share of wealth held by the 19 richest Americans over time:

One such technical assumption is how to attribute the cost of national defense spending – should some of the cost of defense spending be attributed to an immigrant or only attributed to local citizens. One could argue either way, as regardless of whether an immigrant immigrates or not, the defense spending would remain.

The reason we focus on non-college educated immigrants is that for college-educated immigrants, the direct fiscal benefit is already significant positive.

US economic and wage data is used to make the model to better reflect the US economy.

In the hard-sciences (e.g. biology, chemistry), an experiment is when we take two groups and treat one of them with an intervention (for example, a medicine) and argue that any difference of outcomes between the groups is due to the treatment. That is because there shouldn’t be any difference in the group prior to the treatment if the enrollment into the groups was random. In social sciences (e.g. economics, psychology), such experiments are usually not allowed for ethical reasons or feasibility. However, they tend to occur naturally due to laws and regulations that arbitrarily divide people into two groups. For example, two groups with no discernible difference between them: one that receives government intervention and one that doesn’t.

Great article. Thanks for the shoutout!

Yup, in the aggregate immigrants are a net positive for American culture and economy. Most are here presumably to pursue a better life in an opportunity laden and relatively free environment. Having said that, where is the study analyzing the impact of the criminal and chronic welfare consuming elements of immigrants and all the negative elements they bring to the table on indigent American society, and the highly negative blowback on the productive, law abiding immigrant population. Would anyone really care were the undesirable immigrant population and their toxic detritus gone from American society. I think not. An honest look at the impact on American society would look very hard at that aspect of the immigration phenomenon before considering any public communication and remedial action plan. No?