Locked In: How Homeownership Limits Mobility

High house-wealth can unintentionally trap people in an area going through a downturn.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

If you would like to support us in reaching our subscriber goal of 10,000 subscribers, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

I am currently renting in New York City. Whenever I tell my parents and friends how much I spend on rent, I am often told that it is a ‘waste’ of money – I should buy a home instead, as then the monthly payments partially go into the home I get to keep.

The situation above is a common occurrence – the question of renting vs owning a home is a topic that many consider at some point in life. I will not answer the question today but instead, I will discuss an often overlooked part of the discussion – how do renters vs homeowners respond to recessions in their local markets.

Should I Stay or Should I Go

Bojeryd (2024) (an economics PhD student that is currently on the economics job market!) studied how the decision to rent vs own a home impacts a person’s response to economic shocks. Theoretically, if the economic prospects of a city get worse, especially due to a large outside shock, we should expect the city’s population to fall significantly and rapidly. However, we generally do not observe such an immediate strong reaction. How come?

Norway, Stavanger and Oil

Thanks to very detailed Norwegian data we can answer that question. Bojeryd looked at the behavior of people living in the Norwegian city of Stavanger. Stavanger is a city where a lot of the economic output is dependent on the oil industry. During 2014-2016, global oil prices fell by around 50% due to newly developed technologies allowing the US to significantly increase oil production.

This oil shock deeply affected the Stavanger economy:

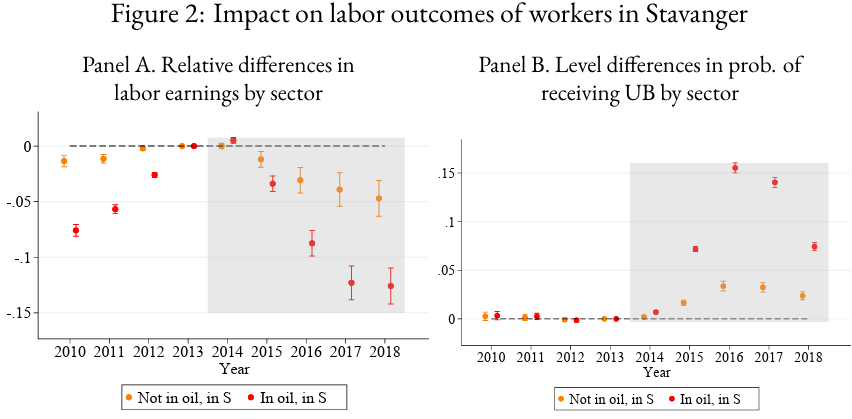

In Panel A of the figure above, we see how the earnings of workers in Stavanger changed relative to those in other areas of Norway. The baseline year is 2013 (both the orange dots and red dots are on zero). A dot below (above) the zero line tells us that in that year, the relative income between Stavanger workers and other Norwegian workers was lower (higher) than in 2013. Thus, prior to the oil shock, Stavanger workers saw relatively faster income growth than the rest of Norway. After 2014, relative incomes fell significantly, with oil workers (red) seeing much larger declines.

Panel B shows the change in workers taking up unemployment benefits relative to the rest of Norway. Prior to the 2014 shock, unemployment benefit uptake in Stavanger stayed relatively the same. But after the oil shock, relative unemployment spiked in Stavanger, impacting oil workers more than others.

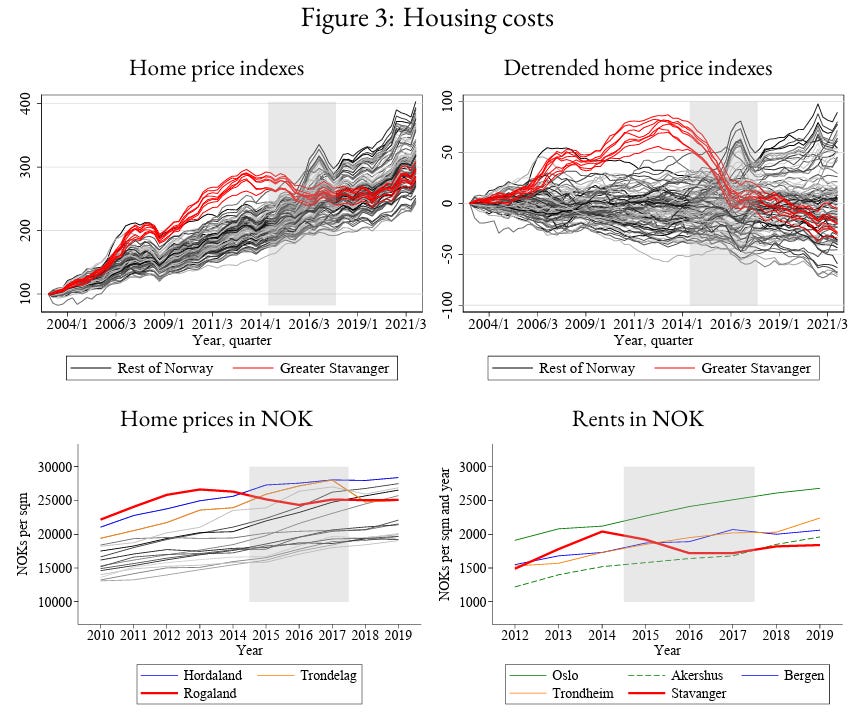

House prices and rents also reacted in Stavanger –

Both home prices and rents in the Stavanger area (Rogaland) dropped during the oil shock, while the rest of Norway had an increase in rents and prices. Home prices and rents in Stavanger fell by around 30% compared to other areas.

Migration Responses

With such a large local job shock, we should expect to see the migration patterns in Stavanger change. With fewer and worse job opportunities, it may no longer make sense to move to Stavanger or remain there.

Bojeryd found that the leaving rate in Stavanger only slightly increased and only for a few years before returning back to normal (and even falling below the previous leaving rate). Migration to Stavanger, however, fell sharply – far fewer people than usual moved to Stavanger. Moreover, the in-migration rate never rebounded.

Who Leaves?

Bojeryd found that renters and low house-wealth individuals increased their probability of leaving. Renters did so substantially, with a 40% increase in probability that they’d leave.

Surprisingly, high house-wealth individuals actually reduced their probability of leaving Stavanger. To ensure that it is housing wealth that appears to reduce migration in response to a negative economic shock, Bojeryd looked at other possible explanations. These were:

proximity to family in the area;

age;

unemployment status;

current income level.

None of the above explained the increased likelihood to stay, as housing wealth did.

The Wealth Shock

One possible reason why high house wealth individuals are less likely to move is due to the fact that they can afford ‘less’ housing in other regions. For example, if previously a person that would sell their home in Stavanger and move to the capital, Oslo, could afford a two bedroom home in Oslo, they may now only be able to afford a one bedroom home, as the price of their home in Stavanger fell.

Because the oil shock was specific to one market, individuals become relatively poorer in comparison to other regions. This makes it more difficult to move, as an individual is taking a loss in ‘real’ terms – if they were to move, they would have to downsize.

Who Moves In?

Bojeryd conducted a similar analysis for the people that migrated to Stavanger. Interestingly, there’s an increase in low income renters and low income-low house-wealth individuals. On the other hand, the probability of high house-wealth people moving in significantly falls.

Based on Bojeryd’s analysis, the increase in low income individuals moving in to Stavanger can be explained in the following way:

Low income individuals are likely to rely on government support (which is fixed typically at a national level);

Falling rents in Stavanger mean the income received from government support can get an individual more housing (and more consumption since less needs to be spent on rent).

This analysis tells us that the people that are not as reliant on labor income, and, therefore, are not impacted by labor market conditions as much, choose to move to Stavanger.

Homeownership Comes with Costs

Bojeryd’s research shows how a local adverse economic shock (fall in oil prices) resulted in a ‘lock-in’ effect for high house-wealth individuals. These individuals that have locked in a lot of their wealth in their homes are stuck between two not good decisions – either lose wealth (by selling their home cheaper) or sacrificing future income growth.

A homeowner has their labor income and wealth exposed to the same risk - the local labor market. As we discussed previously, this should not be surprising as home prices are very closely linked to local income. Thus, any fall in income will translate quickly into a fall in house prices. Potential home buyers are rarely made aware of this risk when deciding to purchase a home.

Without a doubt, it can also be beneficial to be a homeowner over a renter. But it is important to know all the risks/costs related to purchasing a home. Homeownership is often presented as an ‘obvious’ decision and may push individuals into a bad financial situation based on social pressures.

Homeownership is considered to be an important life milestone. Renting is often viewed a bit more negatively. However, the decision to own is rarely presented as taking a ‘bet’ on how the local economy will develop over the next 10-20 years. Adverse local economic developments can be crippling to a person’s wealth and long run earning prospects – you either lose a lot of wealth (selling a home cheaper) or you sacrifice your future income growth. This risk is never mentioned to potential home buyers.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: On the topic of housing, Mike Fellman explains why removing taxes on the gain in home value will probably only push home prices higher.

Article: Guy Berger explains what the recent data on jobs in the US tells us about the US labor market.

Article: Jadrian Wooten goes over how economics (specifically game theory) can help explain video game player behavior in the recent and very popular Arc Raiders game.

Can’t wait to be locked into a 5.5% interest rate on a 50 year mortgage.

Paying from the grave. In certain cities, home ownership is dead.