Revisiting Economic Data – 'Vibecession’

Economic data shows the economy is doing well, but people think otherwise. Maybe we’re looking at the wrong data points.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter that focuses on the application of economic research to current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

We’ve reached out 1,000 subscriber goal by year end. Thank you to all subscribers!

If you would like to help us grow, please consider sharing and liking this article!

About a year ago, I was considering writing this article, but I decided against it, as I thought the topic was over-saturated. The recent US election, however, has reinvigorated the topic of the reason behind the discrepancy between many positive economic indicators and the negative perception of the economy in surveys.

Throughout 2022 and 2023, the term “vibecession”, coined by Kyla Scanlon (a fellow Substacker!), was discussed heavily. The term has gotten so popular that it now has a wikipedia page. Vibecession – a combination of the word ‘vibe’ and recession – was used to describe the economic situation throughout 2022 and 2023. It was an economy that is doing ‘well’, while people perceive things as worse. Many articles were written about it. The recent US election and exit poll surveys renewed the discussion on the state of the US economy, with many people listing the economy as their top concern. So how can we explain the contrast between economic indicators and people’s perceptions?

Economic Indicators

Many economic indicators point to a strong US economy. For example, below is the unemployment chart:

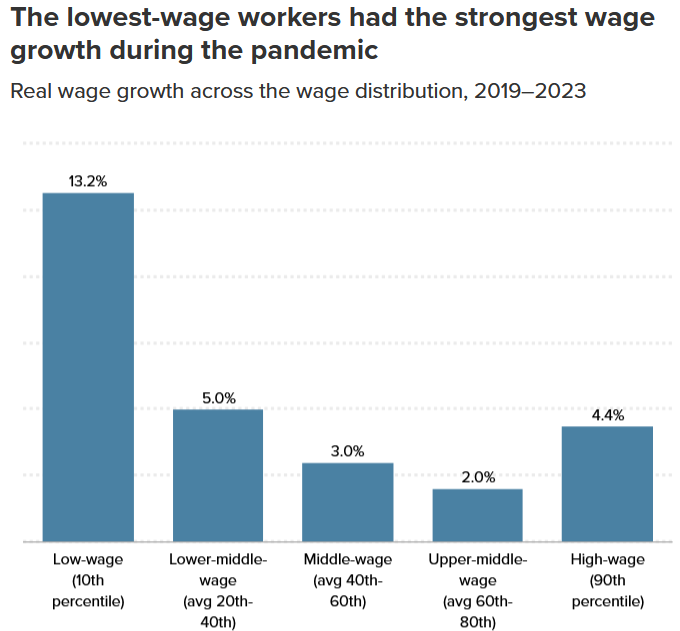

And here is real wage growth across different income levels from EPI:

All of this data suggests that the US economy is doing positively.

Irrational?

However, as mentioned above, people perceive the economy as doing poorly. Many proposed explanations of this discrepancy, such as misinformation, overall negative ‘vibe’ or even inflation, are potentially assuming that people are somewhat ‘irrational’. Generally, I do not like resorting to ‘irrationality’ of individuals to explain a phenomenon, especially if not all ‘rational’ explanations have been looked into.

Rationalizing the ‘Vibecession’

The economic indicators listed above show that the economy is strong, but what ultimately matters for a person is how they are doing financially. Increasing real wages improves people's finances, but only if everything else is held constant (the key assumption in economics).

Everything, however, was not held constant, as many transfer programs that were initiated during the COVID pandemic expired. Below is a summary of all the transfer programs that were implemented during the pandemic:

Many of these programs resulted in significant income increases. Meyer, Han and Sullivan (2024) summarized the following key programs that expired:

One time stimulus payment up to $1,200;

Expanded unemployment insurance – $600 per week;

One time additional stimulus payment up to $1,400;

Enhanced Annual Child Tax Credit by $1,600 (expired in 2021, but some amounts were paid in 2022).

It is therefore understandable that people’s incomes are not only impacted by the wages they are paid, but also what they actually end up receiving after all taxes and transfers are accounted for. Engel and Shantz (2024) looked at the evolution of real post tax and transfer income. Below is a chart that shows how income, after accounting for taxes and transfers, changed since 2016 for three different percentile groups.

Each percentile group’s income has been normalized to their incomes in 2019 (100). For example, between 2019 and 2020, people in the 10th percentile of real income distribution saw a 11% growth in real incomes (moved from 100 to 111). The income for this group then fell from 2020 to 2023 by about 12% (from 111 to 99).

As can be seen in the data, all income groups are worse off since 2021.

As a short caveat, it is worth adding that measuring post tax and transfer income is not easy since such data is not readily available or collected. The analysis shown above is based on using pre-tax data and simulating post tax/transfer income using a tax simulator model used by professional government budget forecasters. However, it is not based on actual data collected.

With that caveat aside, it appears that changes in real income post taxes and transfers can rationally explain the ‘vibecession’ – the money people actually have in their pockets has fallen. Other evidence, such as the measure of excess savings computed by Abdelrahman and Oliveira, has also shown that from around the start of 2022, US consumers started to tap into their savings, which they accumulated throughout the pandemic:

According to Abdelrahman and Oliveira, people have depleted their excess savings, as they had accumulated around $2.1 trillion dollar in savings during the Covid-19 pandemic, but spent around $2.4 trillion of their excess savings since 2021.

Inflation – the Other Explanation

A popular explanation of the ‘vibecession’ and recent electoral trends is that people do not like inflation. Work by Stantcheva (2024) looked at how people perceive inflation. Stantcheva found that inflation is viewed negatively by the public due to concerns of eroding ‘buying power’ and any positives from inflation, such as a stronger labor market, are typically dismissed. The results here suggest that people might actually prefer a world in which inflation is 2% with 3% wage growth, over a world with 5% inflation and 10% wage growth (note: we are disregarding assets and debts in this example, as inflation can play an important role in impacting wealth).

It is also important to put the recent inflationary period in context. From April 2020 to April 2024, the US experienced cumulative inflation of approximately 23%. In a typical 4 year period, the US could expect around 8% to 10% inflation (assuming a 2% target). Thus, current nominal prices are approximately 11% to 13% higher than we would expect to see (or as if we had another 5 years of inflation).

We do not have research that can tell us whether, on its own, this ‘excess inflation’ significantly influences people’s perception. Ultimately, the issue is that due to the expiry of many programs, real post tax/transfer incomes fell significantly, starting in 2021. Had the transfer programs remained, I’m not sure people would find the higher nominal price concerning, especially since inflation was already elevated in 2021 (at 4.7%).

Moreover, in the context of electoral outcomes, preliminary data does not find any patterns between inflation and electoral outcomes. Analysis by the Agglomerations Substack of the Economic Innovation Group shows that in the recent election, there is no correlation between the change in vote share for Democrats and whether a region saw more or less food or housing inflation:

For both kinds of inflation, however, the decline in the vote share for Kamala Harris in 2024 (relative to the Biden vote share in 2020) was remarkably consistent throughout the country. There was almost no difference between counties with the highest inflation rates and those with the lowest.

However, this topic is still being studied and new findings might present a stronger argument.

Real After Tax and Transfer Incomes

The change in real after tax and transfer incomes appears to explain the observed data quite well – strong economic indicators but poor economic sentiment. People simply had less money and went through all their excess savings over the course of the last 3 years. Moreover, when the focus of economic indicators is on pre-tax income or wages, we’re only focusing on around 50%-60% of the population – over 40% of people at any point in time do not work.1 These individuals also saw a fall in incomes.

The decline in real after tax+transfer income might not end up being the definitive answer, as more research and better data comes in. However, I believe it is an important indicator to look at regardless. Unfortunately, real after tax and transfer income is not measured in a timely way – the data, which is based on estimates and modeling, is also tracked with a 1 year delay.

Post Scriptum

As I was writing this article, Nathan Tankus published a similar piece going more in-depth on social safety nets and the notion of different inflation rates facing different people. I highly recommend this read.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Herman van de Werfhorst discusses whether more education increases social mobility. Research suggests it does.

Article: Erman Misirlisoy, PhD talks about the research on mental fatigue and aggression, and provides tips on how to become more aware of this issue.

Note: A short discussion on why tariffs, especially broad tariffs, are likely to increase inflation, holding all else constant. If the Federal Reserve responds (which it will), then real wages will be lower.

This group includes: the retired, students, people who voluntarily do not work or people who cannot work.

I want to RE-register my ongoing complaint that we have NO DATA on real wages becase BLS does not collect _nominal_ wage data. For all I know the remuneration unit value indexes BLS _does_ publish may not be far off. But we do not know.

Great article!