Can Large Tech Companies Be 'Bad' for the Economy but Good for Workers?

Dominant tech firms can stifle innovation, but this may actually benefit their employees.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

Our updated goal for 2025 is to hit 10,000 subscribers:

If you would like to support us further with reaching our subscriber goal, please consider sharing and liking this article!

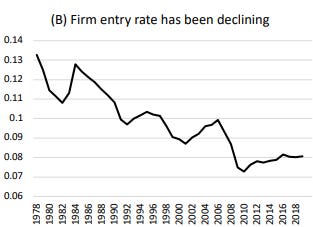

In recent decades, the US (and other countries) have experienced a decline innovation as measured by the formation of new firms:

Many have often pointed blame at the lack of competition and the monopolization of certain sectors. Large companies, especially in tech and pharmaceuticals, have become dominant entities. Opinions on whether such large companies are good or bad are mixed. A recently released paper has looked at how a monopoly, or more precisely a monopsony1, can impact economy-wide technological growth. But interestingly, it may benefit workers in the industry. Let’s dive in.

Modelling a Monopsony Market

Defensive Hiring

Fernández-Villaverde, Yu and Zanetti (2025) (“FYZ”) looked at how market-dominant firms may choose to ‘defensively’ hire in order to prevent being replaced by an incumbent. This question has been often discussed in the context of ‘defensive acquisitions’, where a large firm buys a small firm that is developing a new technology. For example, Ederer and Pellegrino (2023) argued that many start-ups are being acquired by large companies to reduce direct competition.

FYZ have a similar idea, but rather than acquiring companies, large firms may have an incentive to hire more research and development (R&D) workers to make it harder for other companies to innovate. In order to hire more research workers, large firms have to offer higher wages. Since large firms account for most of the hiring of research workers, these large firms are de facto setting the industry-wide wage for research workers. By setting the wage higher, new entrant firms will find it expensive to enter the market.

Does this happen?

The above idea seems plausible, but do we have data potentially supporting such behavior of ‘defensive hiring’. FYZ present several facts that point to such behavior:

In industries where incumbent firms spend a lot on R&D, there are fewer new firms created;

Incumbents that spend more on R&D survive for longer;

Higher incumbent spending on R&D appears to reduce productivity growth.

The above 3 fact patterns are stronger in industries where the supply of research workers is ‘inelastic’. ‘Inelastic’ here means that the total number of people that are available to do research does not increase (decrease) much if the wage given to these workers increases (decreases).

The reason the inelastic supply of research workers may matter is because it implies that the total number of research workers can be thought of as fixed, which means a firm could theoretically ‘hoard’ these workers and prevent other firms from being able to hire any research workers.

Market Power

At the same time, large incumbent firms may have monopsony power. A large firm may typically be the only source of employment for specific research workers. This means that this large firm can use their position and offer lower wages to these research workers since research workers may not have alternative employment opportunities.

Which Effect Dominates

Clearly ‘defensive hiring’ and monopsony power push against each other, as ‘defensive hiring’ increases wages, while monopsony power allows firms to offer lower wages. Which effect dominates is therefore an empirical question. For this, we need a model.

Model – Overview

Incumbent Firm – Monopsony

FYZ propose a model where, in each research sector, there is one large incumbent firm. This firm produces a good. The incumbent firm can innovate each year and become better at producing the good. The probability the incumbent successfully innovates is a function of the number of researchers it hires and the firm's general ‘productivity’. The incumbent’s productivity is a fixed number (typically incumbents have low productivity compared to new firms). The main choice the incumbent can make is to set the wage, which impacts how many workers the incumbent firm hires, and thus how likely it is to innovate.

New Firms

At the same time, each sector also has an unlimited number of potential new firms. Each new firm has a randomly drawn productivity and hires only one research worker (note: this is a modelling simplification that leads to identical results if each new firm hired multiple research workers). The higher the productivity of the new firm, the more likely the new firm will successfully innovate. However, higher productivity draws have a lower probability (i.e. it is harder to come up with a better idea).

If any of the new firms innovate (i.e. become better at producing the good), the new firm immediately ousts the incumbent firm (‘creative destruction’). This new firm then immediately becomes the incumbent and acts the same way as the original incumbent (i.e. going forward, the new firm will hire multiple research workers).

It is worth noting, that for a new entrant to even consider entering the market to dethrone the incumbent, it has to expect to make a profit. The higher the wage the new entrant has to pay to the research worker, the less likely it will make it a profit, making it less likely that a new firm will even consider entering the market.

Setting the Wage

Since each sector is dominated by one incumbent firm, the incumbent firm is able to set the wage all researchers will be charged. This incumbent firm has a dilemma when setting the wage – on the one hand a higher wage means the firm will have lower protifts, but on the other hand, a low wage could increase the likelihood a competitor ‘creatively destroys’ that firm, as more new firms can afford to hire researchers. The incumbent firm is aware of this trade-off and thus takes it into the account when setting the wage.

Results from the Model

Higher Switching Costs

After calibrating2 the model to US data, FYZ were interested to understand how the presence of market dominant firms impacts innovation and wages. Firstly, FYZ noted that it has become harder for research workers to switch which research sector/industry they work in (research has become more specialized, requiring more specific knowledge). In the US, data suggests switching costs between research sectors in the 1996-2019 period are 10% higher than in the 1970-1995 period. In the model, when it is harder for researchers to switch between research sectors, FYZ found that the wage premium (over US median wages) for researchers goes up by 50% (it increases from 12% to 18%). Moreover, the incumbent firm (monopsony firm) hires more researchers, employing 54% of the researchers instead of 48%.\

This result tells us that the ‘defensive hiring’ mechanism (higher wages) is stronger than the monopsony power (lower wages) the firm has. This is because the incumbent firm increases the wage it offers and hires more research workers. Why? Let’s use a hypothetical example.

Suppose the monopsony firm is AI Inc. that specializes in artificial intelligence research. Suppose it is now more costly for other programmers to learn artificial intelligence coding (and vice versa – AI coders would struggle in other programming work). AI Inc. could theoretically reduce the wages it offers to its AI coders, because AI Inc. knows that these workers cannot easily switch into other programming jobs. However, at the same time, AI Inc. knows that by offering a higher wage, it can ‘hoard’ a larger share of AI coders. That is because, even though the wages in AI coding are now higher, other programmers will find it too costly due to higher switching costs to become AI coders and only a few will switch into AI coding. Therefore, AI Inc. can ‘defensively hire’ by capturing more workers and preventing innovation.

This is what happens in the FYZ model – innovation in the economy falls from 1.3% to 1.27% when switching costs went up. At the same time, since the incumbent firm is offering higher wages, there are generally more research workers (AI coders), an increase of 4%.

Harder to Innovate

FYZ also experimented by seeing what would happen if innovation itself is less likely to occur. Matching US data to the decline in innovation, FYZ found that if ‘ideas are harder to find’ (i.e. lower innovation), the number of researchers in the sectors goes up and the research wage premium goes up from 12% to 19%. How come?

If ideas are harder to come by, this means that an incumbent firm is likely to remain incumbent for a longer time, because a competitor is unlikely to ‘creatively destroy’ it. This means it is even more valuable to become an incumbent, because you will earn large profits for a longer time. In turn, this actually induces more firms to enter the market to try to ‘creatively destroy’ the incumbent. Thus, the incumbent again undertakes defensive hiring by offering a higher wage. In this case, however, the incumbent firm has a smaller share of research employees – falling from 48% to 36.5%, as the overall number of new entrants goes up.

The Decline in Innovation

FYZ were interested in understanding the interaction between declining innovation and market concentration. It appears that market concentration coupled with higher costs of research can explain some of the fall in innovation.

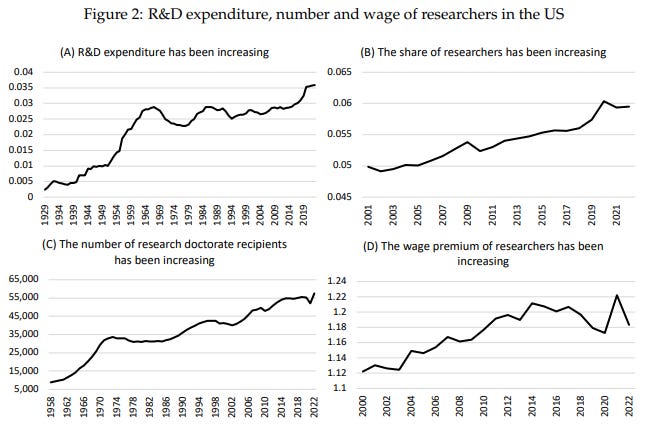

Moreover, the FYZ model can explain some other observed facts in the US economy:

The US is spending more on R&D, and the wage premium for R&D workers has been going up. The ‘defensive hiring’ channel in the FYZ model appears to explain these observed facts.

Policy Implications, Thoughts and Discussion Points

This is a new section I’m trialing where I mention a few potential policy implications and thoughts from the research. Let me know if you find these interesting and please comment if you have any ideas of your own!

The FYZ paper creates several interesting implications:

What might be good for the economy (higher innovation) might not be good for the specific worker (research workers may see lower wages).

FYZ directly tested this by showing that if new firms are subsidized, innovation goes up, but the research wage premium stays the same. If the incumbent is subsidized, innovation goes down, but the research wage premium increases by 50%! It is worth noting that a lot more people benefit from innovation, while only around 5% of US workers are research workers (around 2% of the total population). Solving this trade-off issue (what’s good for the economy might not be good for research workers) may require government intervention via transfers to research workers.

Big firms/monopsonists might be even more beneficial to workers in sectors where training costs are high (it is difficult for workers to join the sector even if wages are high) due to the ‘hoarding’ effect, as wage premiums are higher.

Feel free to comment/share your thoughts in the comment section!

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Chloe East, author of the Cook and East (2024) paper on the impacts of work requirements in SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), discusses at Can We Still Govern? why such work requirements do not increase how much people work and leads to a significant fall in enrollment in SNAP of the most vulnerable.

Article: Emaan Siddique goes over the research on how access to menstrual hygiene products improves educational outcomes for girls.

Article: Keshler Thibert explains the historic and current political situation of Bosnia and Herzegovina via an interview with the director of the War Childhood Musuem. Since the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina the 90s, the country has been split into 3 administrative areas, each with their own leader.

A monopsony is a firm that is the only buyer of a good or service (e.g. hiring of workers).

Calibrating a model means setting parameters in the model in order to match certain features of the economy in question. In this case, it is the US economy and the features that are matched are the share of research employment in total employment (5.5%), incumbent’s share of research employment (48%), research wage premium (12%), creative destruction probability (13%) and the technological growth rate (1.3%).

In the late '50s and into the '60s the aircraft industries in Southern California were operating in similar fashion to hire engineers and management personnel. Nothing new really. In fact the practice was the genesis of benefits like medical and dental. They were carrots to attract the largest population of applicants from which there was the better draw of talent. Personally I see the largest problem in today's business environment is the big fish are allowed to gobble up the little fish to acquire technology or squelch competition. It is on par with the dismal pickings from the American labor pool because too many potential employees may be attractive on paper rather than in actuality simply because of the sorry state of the American education system. American competitive capitalism is great until it becomes predatory; predation is built into the model. Obvious since the days of ma Bell and likely through out all human history. It is an unfortunate part of human nature; just like war.

Glad you found my article interesting!