GDP Will Reflect “AI”, But How Focused Should We Be On It?

Podcaster Dwarkesh Patel believes the value AI will not be accurately reflected in GDP – he’s both right and wrong

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research on current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

If you would like to support us in reaching our subscriber goal of 10,000 subscribers, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

Should we care about Gross Domestic Product (GDP)? Does GDP reflect what matters? Is GDP a good measure? Recently, an influential tech podcaster and interviewer, Dwarkesh Patel, brought up the topic in the following context:

“As measured by GDP, AI will be super undervalued. How would the datacenter of geniuses show up in GDP? GDP would show raw inputs (aka chip & energy), and raw outputs (aka cost of tokens). But wouldn't clearly reflect the value of the crazy new [stuff] that's being cooked up in those tokens. Similar problem to how the Internet's value is undercounted today (since many products are free, and thus contribute nothing to measured GDP).”

Dwarkesh Patel is both right and wrong. To understand why, we need go over what is the GDP measure, why we measure it, and does it capture what matters to us.

Article Overview

Section I. Creation of “GDP” – the history of the measure and what it exactly measures

Section II. How AI (and other technologies) impact GDP – why low cost production such as AI will show up in GDP

Section III. Beyond GDP – what else matters for happiness

I. Creation of “GDP”

The GDP measure was invented by Simon Kuznets, a Nobel-Prize winning economist around 1937. It started to be used globally in 1944, after the Bretton Woods conference.1 The measure itself is relatively simple: it attempts to value the overall economic output of a given country by using the transactional value (in currency) of goods and services. Broadly, GDP (“Y”) comprises the value of consumption (i.e. goods and services you buy), investment (i.e. people's savings that are used for investing into things such as infrastructure, research etc.)2, government spending, and lastly net exports (i.e. the difference between exports and imports). GDP is simply an accounting identity, often written out as:

Y = C (household consumption) + I (business investment) + G (government spend) + NX (export minus imports)

As a brief aside, the last variable – net exports – has often been misinterpreted as implying that imports subtract from GDP. They do not. The reason why we include the net exports variable is because imports are actually included in the other variables of the formula – mainly consumption and investment. If a person imports an avocado and eats it, we would count this value in “C”. Since the country did not produce this avocado, we want to subtract it from the output calculation. The acquisition of the avocado has no impact on GDP whatsoever as it adds to C but is subtracted via NX.

Over time, the GDP measure became an important metric in public discourse due to the strong positive correlation between the GDP measure and many other welfare metrics, such as life expectancy, nutrition, and infant mortality. However, it is worth noting that Kuznets himself did not want GDP to be linked with the broad concept of welfare, which can be thought of as the well-being of society.

II. How AI (and other technologies) impact GDP

Dwarkesh Patel brings up the concern that since using AI is not costly, AI’s impact on GDP will be negligible. Now this notion is not new. Martin Hagglund, author of “This Life” (a book I recommend), brings up a similar issue in the context of cheap access to water:

“Let me take a simple example that I elaborate at length in the book. Let’s say that in a village we develop more and more efficient technologies for acquiring water, and we end up with a well in the middle of our village. As a result we are wealthier in an existential sense, since we have freed up time to do other things besides go and get water out of necessity. But if the water is not produced through wage labour and it doesn’t cost anything to buy the water – in short, if the water is not commodified – then the production of water is not generating any wealth in the capitalist sense.”

Hagglund shows that the well in the village will not directly contribute to GDP, but nonetheless it will be extremely valuable. Hagglund’s example highlights Patel’s AI point very well – utilities (of which water is a subset) form just 1.5 percent of US GDP, their true value to daily life is far higher.

In his argument, Hagglund is correct that easy access to water is very valuable as it frees up time for us to do things we want to do rather than have to do. Although Hagglund doesn’t mention this, this is exactly how such new technology impacts GDP – it gives us time to do other things that will often result in other production which generates GDP. If fetching water once a day took an hour, the well frees up 365 hours of labor per person annually, which can now be applied to other jobs that create output or leisure. The true impact of utilities on the economy is probably much greater than the 1.5% of GDP.

It’s not true, therefore, that the impact of AI or utilities is not captured by GDP. Even if these things would be free, the impact from freeing up human time and creativity drives other economic activity that ultimately is captured by GDP. It’s just that tracing this secondary impact may be difficult.

Moreover, Patel and Hagglund touch upon the fact that time saving technologies may also translate into increased ‘leisure time’, which might not show up in GDP, but still be a benefit. This brings us to the discussion of what are the limitations of GDP.

III. Beyond GDP

GDP is not considered to be a great measure of welfare by many economists. In 2018, Joseph Stiglitz said the following:

“GDP is not a good measure of wellbeing. What we measure affects what we do, and if we measure the wrong thing, we will do the wrong thing. If we focus only on material wellbeing – on, say, the production of goods, rather than on health, education, and the environment – we become distorted in the same way that these measures are distorted; we become more materialistic”

One measure proposed by Jones and Klenow (2016) suggests taking into account a variety of additional factors, along with GDP, – leisure time, inequality, and life expectancy. In their work, they start their analysis by noting the welfare issues of GDP with an example. In 2005, French GDP-per-capita was 67% of the US. By using just GDP, we could erroneously assume that life in France was a third worse. However, life expectancy in France was higher (80 vs. 77 years in the US), hours worked were lower (Americans worked 877 hours per person annually, as compared to 535 hours for the French), and inequality was significantly lower. Clearly, the GDP measure did not paint a full picture.

Jones and Klenow decided to take the above factors into account when creating a single measure, which they refer to as ‘consumption-equivalent’ welfare. The idea is to convert all important welfare factors into a common unit of consumption-equivalent welfare (in the case of GDP, the common unit of valuing everything is currency). In order to create this unit of measure, the authors estimate values that enable them to compare, for example, how much extra consumption is 1 hour of leisure time worth.

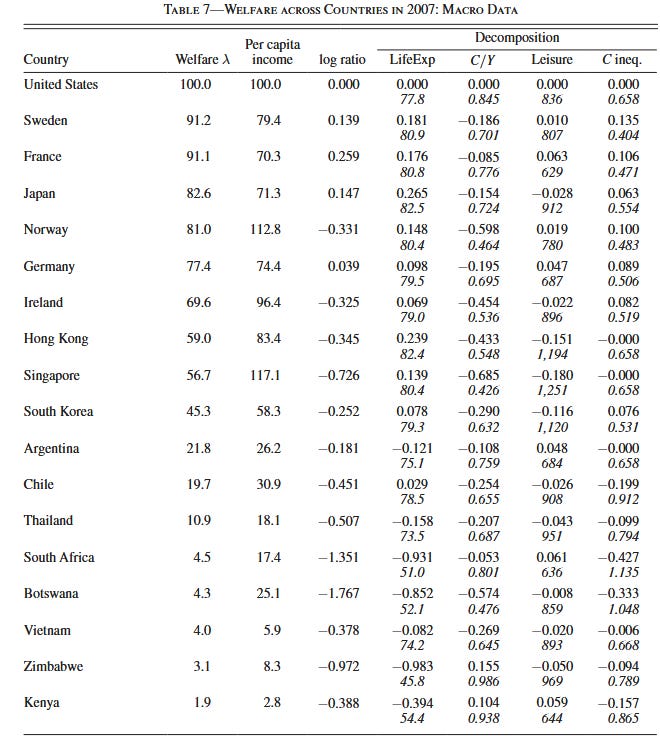

Naturally, these estimations will all depend on the country in question (1 hour of leisure in one country might be more valuable than the same amount in another). After creating this consumption equivalent welfare unit, which includes GDP, leisure, life expectancy and inequality, they can compare countries directly. Based on their measure, they got the following results for 2007 (to interpret the table, Sweden has 91.2% of consumption-equivalent welfare of the US, which means Swedes have 8.8% less welfare than Americans).

This is just one potential approach to an all-encompassing single measure.

Connecting GDP and Happiness

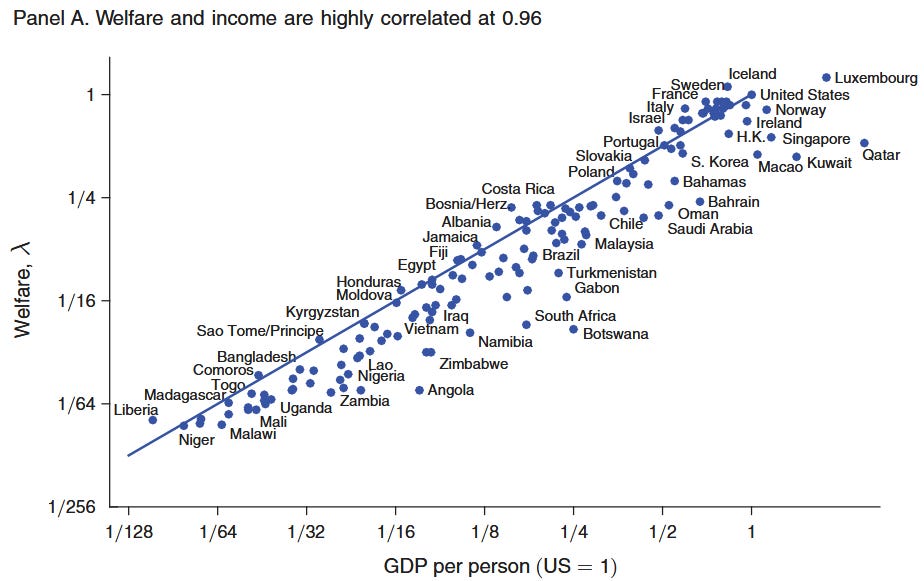

Nonetheless, even when taking into account these other factors (leisure, life expectancy, inequality), Jones and Klenow show GDP on its own is still a pretty good proxy for welfare:

But as they mention, this correlation hides significant differences between how well countries convert income into welfare:

In the above chart, a country above 1 is able to ‘convert’ GDP into welfare at a higher rate than the US. On the other hand, countries below 1 are worse than the US. Thus, for example, based on the Jones and Klenow measure, Qatar, which has very high income per capita (x-axis), is very inefficient in converting this high income into welfare.

Production Function of Welfare

This brings me to an interesting idea – what if welfare and happiness can be thought of similarly to how we think of production. Let’s borrow a formula commonly used in economic growth theory.

GDP is a multiplicative function of 3 parameters – capital (machines), labor (workers) and a technology that converts these two inputs into output. This is often denoted as:

where A is the technology parameter, K is capital, L is labor, and F is a mathematical function over capital and labor.

If we use a similar approach to welfare and happiness, then the welfare of a country can depend on income (GDP) and a ‘technology’ that multiplicatively converts income into welfare:

where we can denote H is the happiness/welfare technology, while Y is GDP per capita. That is, if Y is $50,000 per capita, and we have an H of 1.2, overall happiness would be equivalent to $60,000 ‘welfare units’.

This formulation tells us two things:

As GDP per capita increases, welfare increases, which matches what we often observe in the data, as well as the Jones and Klenow result;

The H parameter, just like the technology parameter in the production function above, tells us how effectively a country converts income into welfare/happiness.

This idea of a ‘technology’ that converts income into welfare has been mentioned by Hulten and Nakamura (2022). Hulten and Nakamura explain this technology via a culinary example – a meal is often more valuable than the sum of its food ingredients. Moreover, this can be further augmented – a dinner party can be more valuable than a meal!3 Thus, this H ‘technology’ reflects how well we convert income (food ingredients) into welfare (a successful dinner party).

The ratio between GDP and welfare computed by Jones and Klenow on the second scatter plot above can give us a first estimate of this H ‘technology’ – countries like Cyprus, Iceland and Liberia have a very high H, while countries like Qatar and Botswana have a relatively low H. What impacts this H – whether its institutions or other factors – would be an interesting topic of study.

GDP – It’s Only a Measure

GDP is a useful measure, as long as its limitations are well understood. The concerns brought up by Patel and others around this measure are valid, but these concerns are primarily driven by the fact that we confer a lot of meaning to this measure, well beyond what the measure states to do. GDP is not the issue – it’s our over-interpretation of it that is.

This fact has been picked up on by many government institutions, including the European Union, the OECD and the Bureau of Economic Analysis, that are now working on developing new measures, commonly referred to as ‘Beyond GDP’. Hopefully, these initiatives will come to fruition.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Sanket Sen and ProfAnanish discuss how punishing crime severely could be the a driver of inequality. Using a laboratory experiment, they found that:

when punishment is applied under conditions of imperfect information, it can itself become a source of inequality. Our experiment showed that when enforcement relies on noisy or unreliable signals, even well-intentioned punishment risks doing more harm than good – reducing cooperation and widening inequality.

Article: Andy Boenau talks about how asking ‘dumb’ questions can lead to important insights regarding urbanism. I’d say that this approach is as important in economics – we need to more often ask ‘dumb’ questions.

Article: Matthew E. Kahn discusses how certain innate features of Europe, as well as policies, may be preventing the continent from investing into air-conditioning, even though this lack of investment might not be justified.

This was a conference of delegates from 44 allied countries to establish a regulatory system for the international monetary and financial order after World War II.

Note – this is not the same “investing” done by buying stocks on the secondary stock market. This activity does not get counted in GDP.

Hulten and Nakamura argue that one key factor missing from all welfare measures is the ‘consumption technology’ level influencing our lives. They base their theory from Kelvin Lancaster’s insight that welfare depends on the characteristics of goods consumed and not on the goods themselves.