Work Requirements

Part of the negotiations over the debt ceiling focused on including work requirements as part of the certain welfare programs. Do work requirements ‘work’?

This week we're trialing another feature – an additional section at the end of the article linking to interesting notes or articles that caught our eye this week. Let us know in the poll below if you found it beneficial!

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. Please consider supporting us and sharing this article in various social media!

Introduction

The US has a unique law regarding its debt – the amount of debt it can issue overall is limited by law, currently at $31.4 trillion. As the US approaches the debt limit, cross-party negotiations are typically necessary to raise the debt ceiling – or at least that has been typically the case.1 At the moment of writing this article, there appears to be an agreement to raise the debt ceiling.

We will not be focusing on the negotiations or whether the debt ceiling is useful or harmful, but we will discuss one aspect that occurred during these negotiations. Certain Republican party members have requested the addition of ‘work requirements’ to certain federal assistance programs, namely SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), which assists needy families with the purchase of food. Work requirements have long been discussed in the context of welfare programs, as something that is necessary to encourage individuals to find work, rather than rely on assistance programs.

As with any economic or social issue, we can ask – what is the impact of work requirements and do they achieve their aims?

What are Work Requirements

Work requirements are additional policies added to specific government programs that require the individual to have worked or attempted to find gainful employment in order to receive the benefit. Work requirements are usually considered in the case of welfare programs.

The topic of work requirements was best theoretically described by Besley and Coate (1992). One thing that is taught nearly universally at every introduction to economics course is that people respond to incentives. Based on this, economic theory suggests that if people receive certain benefits, such as money for food, below certain income thresholds, it disincentivizes them from working. The idea is that when they start working and make sufficient incomes, they will no longer be eligible for the food assistance program. Therefore, they might try to ‘game’ the system by not working at all, as then they will receive the benefit. This is referred to as the screening issue of welfare programs – ensuring that the appropriate individuals receive the benefit.

Another reason for work requirements is what Besley and Coate refer to as the deterrent effect. This issue focuses on the reason why individuals need assistance – is it due to circumstance and bad luck, or is it due to specific choices made during the individual’s life. If it is the latter, the concern is that individuals might not have incentives to prevent themselves from falling into poverty since they will receive benefits that will assist them. Work requirements make these benefits ‘less attractive’ as it will still require effort to receive the assistance. Thus, this will deter individuals from falling into poverty.

It is worth noting, and Besley and Coate emphasize this point as well, that the screening and deterrent effects are only described in terms of income and not utility (also known as welfare). The difference is that utility incorporates both income and leisure – work requirements will definitely reduce leisure, which in turn reduces utility. However, the lens through which work requirements are usually assessed are via income, not utility.

The Besley and Coate model gives many theoretical results that argue when work requirements are beneficial and when they are not. Their theoretical results typically suggest that it is optimal to have either no work requirements whatsoever or very high work requirements. Which of the two policies is optimal depends on what factors are easily observable, such as a person’s earnings and ability.

Apart from theory, what does the data tell us about work requirement impacts?

Work Requirements – Data Issues

One of the most recent studies to look at work requirements for SNAP recipients was done by Gray et al. (2021). Before going into the results of their analysis, it is important to describe why evaluating the impact of work requirements is difficult.

Most previous studies that looked at the impact of work requirements used survey data. As we discussed previously, survey data has a lot of issues, including lack of incentive to respond honestly, lack of responses, or individuals failing to participate in follow up surveys.

Another issue is determining what is the appropriate sample of individuals to be studied. For example, focusing only on individuals that receive the SNAP benefit already, excludes all individuals that are eligible for the benefit. Moreover, individuals might pre-emptively react prior to the implementation of work requirements and increase their labor in order to not lose access to the benefit. Thus, depending on the timing of the study, we might wrongly assume that people aren’t responding to work requirements, but that’s because they already have responded by increasing how much they work. Some have argued that this is why the economic literature has not found many benefits of work requirements, such as this analysis by Rachidi and Doar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Gray et al. deal with these issues by following a specific set of individuals over multiple years. Prior to 2009, the state of Virginia had a work requirement for SNAP participation for able-bodied adults without dependents (ABAWDs) below the age 50. After the age of 50, the work requirements were less stringent. Due to the Great Recession of 2008, the Federal Government suspended state work requirements. From 2009 to 2013, work requirements for SNAP eligibility were suspended. All ABAWDs that were enrolled in SNAP during this time were the sample of individuals Gray et al. analyzed. As there were no conditions, besides being low income, this is a good proxy for all individuals that would choose to enroll into SNAP.2 After 2013, the work requirements were reinstated by Virginia.

Since the sample of individuals that used SNAP is thorough given anyone below a certain income could participate, the reinstatement of work requirements will allow us to determine how these individuals respond to the change in laws. Do they work more? Do they drop out of SNAP?

Work Requirements – Results

The reinstatement of work requirements can impact individuals in three different ways. First, individuals might choose to fulfill the work requirement to maintain access to the SNAP benefit. Second, individuals might not be able to satisfy the work requirement and drop out of SNAP. Lastly, individuals that are unable to satisfy the work requirement, might still choose to increase work hours in order to make-up for the loss of the benefit.

Due to the nature of the Virginia policy change, a natural experiment occurred.3 After 2013, some individuals that were just below the age of 50, now faced strict work requirements, while other individuals that were above 50 did not. Gray et al. were able to track outcomes of both of these groups and determine whether any of the effects occurred due to the reinstatement of the work requirements. Their key results were:

Work requirements dramatically reduced SNAP participation. WIthin 18 months, participation of individuals just below the 50 year age cutoff dropped by 53%.

The impact on employment is limited – the estimated impact of work requirements on employment was zero.

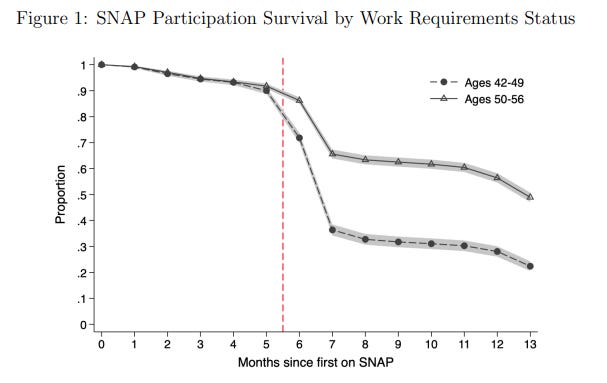

Visually, the drop in SNAP participation can be seen in the graph below:

The graph tracks the individuals that were enrolled in SNAP and what proportion of these individuals remained in SNAP. SNAP work requirements had a 6 month exception period – for the first 6 months the work requirements were paused, which is why the red cutoff line is shown between 5 and 6 months. As can be seen, right after the work requirements became binding, the difference in participation rates of individuals above 50 (the individuals that work requirements did not impact much) and individuals below 50 years old (individuals for whom work requirements were bindings), significantly widened.

Moreover, regarding SNAP participation, the individuals that stopped participating were also some of the most vulnerable. Individuals that were homeless or had no income prior to the reinstatement of the work requirements were most likely to stop participating in the program. In contrast, individuals that had disabilities, and therefore were exempt from work requirements, did not exit from SNAP. Since for individuals with disabilities, work requirements have no impact, as they can receive a waiver, this result is entirely expected. This serves as a test of the data – since we observed something that was expected, it is unlikely for there to have been data collection issues with the study.

The result of this study regarding employment impact is not unique. Studies, including Stacy et al. (2018) and Ritter (2018), have looked at the impact of work requirements of SNAP and found that there is usually no labor response of the individuals, but SNAP participation rates drop. At most, studies such as Harris (2018) and Han (2022) have found work requirements in SNAP increasing labor participation rates of 1 to 2 percentage points (this effect is mainly concentrated on individuals closest to the cutoffs - numerically this would increase employment by approximately 76,000, which is similar to the number of newly unemployed every week).

Conclusion

The SNAP work requirements have no economic merit – they do not result in increases in labor participation. They do reduce participation in SNAP, especially among the most vulnerable and in need of this assistance.

The above studies, however, have not fully addressed the impacts of work requirements, as research on the deterrence effect (that is, with the work requirements, there is no social safety net to assist them when they’re poor, so individuals are more likely to act differently throughout their life) is limited. Nonetheless, even if work requirements do deter people from falling into poverty, the above studies have also not included the additional costs and indirect effects work requirements cause. Verifying work requirements is costly, which requires additional administrative burden. Furthermore, families and individuals that lose SNAP benefits (or do not receive them in the first place) result in significant costs to society as well.

As we showed before, early childhood investment is critical for development and has tremendous benefits to society. Removing nutrition benefits can adversely impact the development of children. SNAP has also been shown by Carr and Packham (2019) to reduce crime. This was true for grocery thefts, which were shown to spike when SNAP benefits run out.

SNAP is a great program. Adding work requirements is simply hurting the most vulnerable – the homeless and individuals with no income – which further sets them back.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Pascal Michaillat demonstrates how the recent media coverage of the vacancy (number of job openings) to unemployment ratios are missing the point when they talk about 'fake vacancies'.

Tweet: Production prices appear to be cooling as shown by Robin Brooks. Input and output prices are dropping, along with shipping and transportation costs.

Substack Note: If Inflation Nowcasting (the Cleveland Federal Reserve model for forecasting inflation) forecasts are accurate looking into June, we would expect a large fall in inflation in June in the US.

Substack Note: Median newly built home prices have dropped 15% from their peak.

Tweet: Full pay transparency might not lead to what we think. Research suggests that pay transparency reduces workers bargaining power since firms are credibly worried about having to raise pay for everyone if they do so for one worker.

Cover photo by kellymlacy.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Housing – Will deregulation fix everything? – would removing zoning laws and housing regulations lead to an increase in housing supply and improve housing affordability.

High Profile Layoffs – how the recent layoffs in the tech sector will affect the wider economy.

To Compete or Non-Compete – why non-compete clauses do not solve any issues, but only create costs.

Some have argued that even if the debt ceiling was reached, other US laws does not allow the President of the US to stop funding programs, creating a situation where both actions – breaching the debt limit or not funding government expenditures – are in violation of law.

People who did not enroll in SNAP, even if they could have, are typically referred to as ‘never-takers’. That is people who will not participate in a program regardless of how easy or difficult it is to enroll. Since these people will never enroll into SNAP, changing SNAP policies will have no impact on their behavior.

In the hard-sciences (e.g. biology, chemistry), an experiment is when we take two groups and treat one of them with an intervention (for example, a medicine) and argue that any difference of outcomes between the groups is due to the treatment. That is because there shouldn’t be any difference in the group prior to the treatment if the enrollment into the groups was random. In social sciences (e.g. economics, psychology), such experiments are usually not allowed for ethical reasons or not feasible. However, they tend to occur naturally due to laws and regulations that arbitrarily divide people into two groups. For example, two groups with no discernible difference between them: one that receives government intervention and one that doesn’t.

"The SNAP work requirements have no economic merit – they do not result in increases in labor participation. They do reduce participation in SNAP, especially among the most vulnerable and in need of this assistance."

Not disagreeing with this, but if people generally don't work and simply drop out of the program instead, doesn't this challenge the notion that this program was needed in the first place?