Should Reward Credit Cards Be Banned?

While credit card issuers collect higher fees, rewards are paid for by everyone

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research to current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

In the US, rewards for using credit cards are immensely popular – Americans received around $40bln in rewards in 2022. However, although ‘rewards’ make it sound like a positive program, research shows that these rewards-based credit cards increase costs for all and exacerbate inequality by transferring from poorer to richer individuals (as well as ‘naive’ individuals to ‘sophisticated’ individuals).

Credit Card Rewards

Credit card usage in the US is ubiquitous, accounting for around $6trln in spend in 2022. These credit card transactions come with a cost – around 1.5% to 4% of the sale price is the cost to the merchant of conducting a credit card transaction. This fee is split between the network provider (like Visa and Mastercard) and the credit card issuer (usually a bank or credit card company).

To encourage usage of credit cards, credit card issuers offer rewards in the form of ‘cash back’ or points (these points can be redeemed for cash or used to purchase items or services).

Naturally, since corporations are in the business of making profits, who ultimately pays for these rewards and why do rewards cards exist at all?

Different Payment Methods - Different Costs

To tackle these questions, Felt, Hayashi, Stavins and Welte (“FHSW”) looked at US and Canadian transaction data made with cash, debit cards or credit cards. Each of these methods incurs a different cost - cash payments may require ATM fees for individuals to get the cash, while debit cards and credit cards have various transaction and network fees. In the credit card world, these fees are actually quite varied.

Credit Card Fee

When a customer uses a non-rewards credit card, the merchant pays on average 1.89% of the transaction amount as a fee (this is referred to as the ‘merchant discount rate’). A basic rewards card typically has a 2.04% fee, while a premium rewards card has a 2.49% fee.

Credit Card Reward Rates

FHSW also computed the average rewards consumers get as a percentage of spend (after fees) – a basic rewards card nets around 0.75% in rewards, while a premium rewards card nets around 1.5% to the user.

Do Merchants ‘Discriminate’?

Based on the above data, it would be logical to ask if merchants charge different prices based on the method of payment. Briglevics and Shy (2014) looked at this question and determined that merchants would likely not benefit from such behavior.

Merchants could at most offer around a 1% discount to encourage other forms of payment (cash or debit cards). However, the profit this would generate is unlikely to cover the costs of offering different prices (confusing customers with different prices; sales delay by having to explain the price difference; customer distrust when seeing different prices).

Given that merchants are unlikely to price discriminate, who then pays the cost of the credit card fees?

Cash Payers Subsidize Card Payers

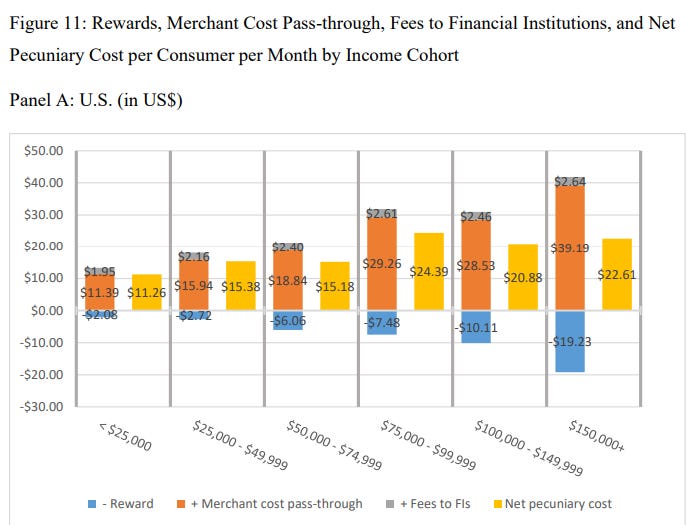

FHSW, under the assumption that 90% of the card fees gets passed on to consumers via a flat increase in price on all goods/services, found that the majority of the total cost is borne by high income households:

As the chart above shows, after accounting for rewards, high income individuals, on average, spend $22.61 a month to cover credit card merchant fees, while low income households spend $11.25.

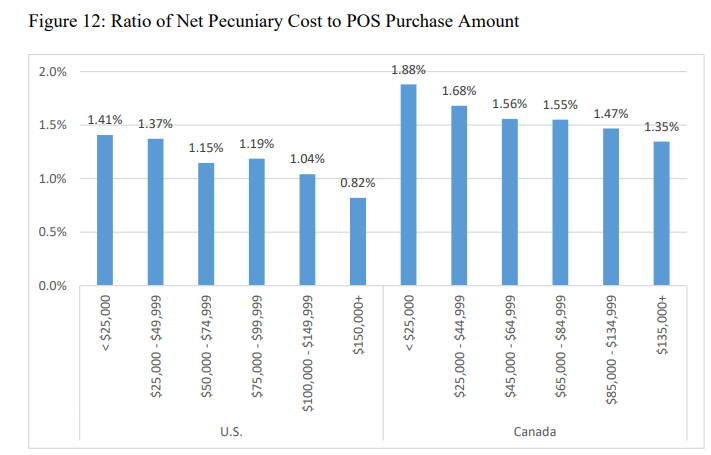

This fact isn’t surprising as high income individuals spend the most. However, as a percentage of spend, the lowest income households pay the largest amount:

On the left we see the US data, which tells us that 1.41% of the spend undertaken by individuals with an income of less than $25,000 goes to cover transaction costs. As can be seen, higher income individuals (above $150,000 annual pay) pay only 0.82% of their spend in transaction costs.

As merchants charge the same sticker price, the higher reward credit cards, which are costlier to merchants, are in effect subsidized by lower income households who often do not have access to these credit cards in the first place, as they rely on cash instead. It’s also worth noting that this analysis does not include any credit card interest payments that may be due.

Sophistication Between Credit Card Users

FHSW research looked at all payers – cash, debit cards and credit cards, and focused only on the transaction costs. What if we focus solely on credit card users and the interest payments associated with credit cards? Agarwal, Presbitero, Silva and Wix (2025) (“APSW”) did just that.

APSW used a US dataset that contains granular information on individual’s credit cards, including information on credit limit amounts, how much has been borrowed, the interest rate on the credit card, the repayment amounts and the FICO (Fair Isaac Corporation) score (Note: the FICO score is a metric that aims to capture the credit riskiness of an individual borrower).

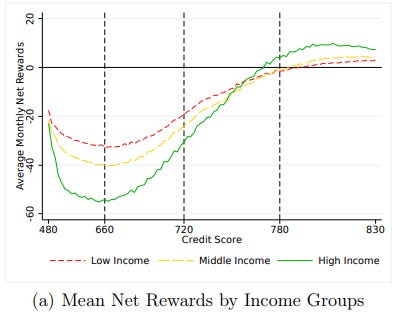

APSW looked at “Net Rewards”, which is the rewards a credit card user gets minus the fees and interest they paid on the card. What they found is that FICO scores predict whether an individual benefits from the card or doesn’t.

The chart above shows that income is not a predictive metric of reward benefits, as high income (green line) low FICO users seem to have quite high costs with reward cards. So what explains why FICO scores may matter regarding benefiting from a card?

Testing for “Sophistication”

APSW argue that high FICO users are more ‘sophisticated’ financially, as they are better at optimizing their finances, than low FICO users. APSW test sophistication in the following way.

In their data, APSW observe whether an individual received a credit limit increase initiated by the bank (i.e. the credit card holder can now borrow more). APSW found that both low and high FICO users increase the amount they borrow after a credit limit increase, but only high FICO users also increase how much they repay of the borrowing, while lower FICO users repay the same amount as before. This suggests that high FICO users are able to forecast their cashflows better than low FICO users.

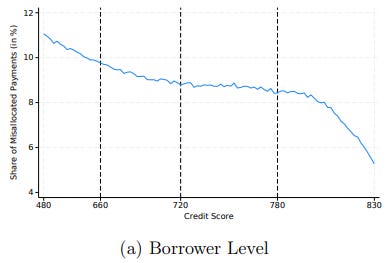

Additionally, high FICO users appear to optimize which credit card they repay, focusing on higher interest rate cards first. On the other hand, lower FICO users use ad hoc rules of thumb such as repaying a fixed percentage of each credit card balance, which leads to an overall higher interest payment.

The chart below presents the share of ‘misallocated’ credit card payments (i.e. the individual would have been better off to use their payment to pay off a higher interest rate credit card):

Bank Profits from Credit Cards

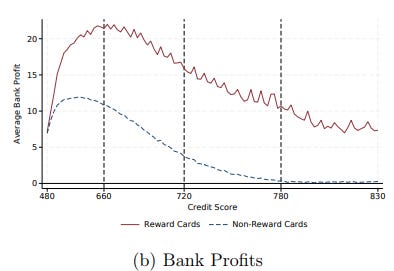

APSW also looked at the profits banks receive from different types of credit cards – reward credit cards vs non-reward credit cards. The chart below shows the profitability by card type and FICO score for banks:

Reward cards generate significantly higher profits than non-reward cards. What’s worth noting is that reward credit cards often have lower interest rates on them vs non-reward ones. The higher profits banks make on rewards cards mainly come from the higher interchange fee (the fees paid by merchants) and the fact that people appear to borrow more on rewards cards.

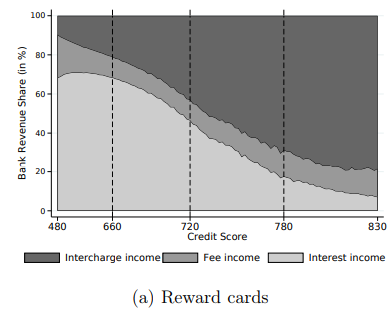

APSW showed how these different sources of revenues are split by FICO scores – the table below shows that banks receive most of their revenues from low FICO users from interest payments, while interchange income (i.e. the fees merchants pay) is the main driver of income from high FICO users:

Rewards Cards – The “House” Always Wins

The findings from FHSW and APSW show that credit card reward programs are mainly funded by transfers from cash payers to credit card payers, and transfers from ‘naive’ individuals to ‘sophisticated’ ones, with the credit card issuer taking a profit margin.

Now, a certain profit margin makes sense – the banks and credit card networks provide a service for which they ought to be compensated. The concern to me is that rewards programs, with their higher interchange fees, simply increase costs on all consumers with no added value. Non-rewards cards are cheaper to operate and provide an identical level of service from the credit card companies to the service offered by rewards cards. The only difference is the ‘rewards’ feature which is ultimately a transfer of money from one group of individuals to another, akin to what happens gambling. The credit card issuer pockets a higher total fee from merchants under rewards cards than non-rewards cards, which is why they choose to issue such cards.

Rewards cards take advantage of people’s behaviors by increasing indebtedness and inducing extra spending through the promise of rewards. At the same time, merchants also have to pay a higher cost for rewards cards. Neither of these aspects appear to be welfare improving, and the only beneficiaries are, on average, richer and more ‘sophisticated’ people.

Thus, there is reason to ban rewards credit cards, as they appear to be more predatory than welfare improving. Generally, I don’t like bans as a policy tool, so another possible solution is simply placing a tax on rewards and cash-back, treating it in the same way as income. This would likely significantly dissuade the usage of rewards cards.

P.S.

Incidentally, right as I was finishing this article, the US announced plans to limit credit card interest rates to 10%. The stated goal of this policy is to improve outcomes for consumers. Without getting into much detail, such an interest rate will likely result in reducing access to credit, which is negative to people’s welfare. On the other hand, banning rewards cards would likely be a better option as it may encourage more competition amongst credit card companies on interchange fees they receive from merchants. Since there will be no varied rewards programs, credit card companies would have to differentiate themselves with their level of interchange fees to encourage merchants to use their card and gain more market share. These lower fees would be passed on to consumers.

If you would like to support us in reaching our subscriber goal of 7,000 subscribers, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Natalie Wexler discusses how research findings sometimes may not replicate and its important to update ones beliefs. In this case, research which suggested that turning on subtitles for children improves their reading ability may not necessarily be true.

Article: Tommy Blanchard goes over how utility and preferences can impact our choices (especially why someone may prefer bad coffee). What might seem ‘irrational’, in economic terms, might be perfectly rational!