Something is rotten in the state of … Economics

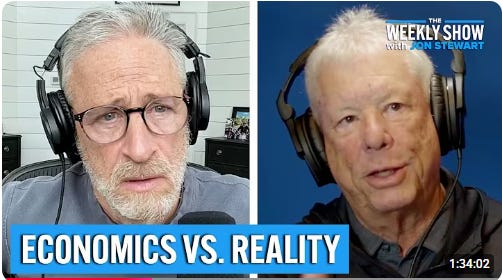

A recent podcast with Jon Stewart ignited a debate about economics

Nominal News is an economics newsletter written by a PhD Economist that translates the latest economic research into clear, policy‑relevant insights on current issues. Join 4,000 readers for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

On February 4, Jon Stewart – a well-known American comedian/writer/political commentator – interviewed Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler. The discussion touched on several economic topics like healthcare and climate change. The interview itself was relatively inconsequential, but there was significant fallout post the interview with numerous economists and economics commentators criticizing Jon Stewart harshly for what was viewed as very dismissive comments about the field of economics.

I listened to the interview and I see it as a classic case of economists and non-economists talking past each other. But I don’t think the avalanche of criticism against Stewart heaped on by economists was justified.

Economics in Trouble

I am a PhD-trained economist, and I believe economics is both an important and useful subject. Economics studies human decision-making; these insights are invaluable for policy discussion. I also believe that the majority of PhD-trained economists conduct research in good faith, with the aim to gain a deeper understanding of human behavior, which often results in better policy making.

In the interview during the a discussion on climate change policies, however, Jon Stewart said the following about economists:

“So my point is, since when is economics about improving the human condition and not just making money for the companies that are extracting the fossil fuels from the Earth?”

Stewart’s view of economics is starkly different from mine. It is an incorrect view, but the reason Jon has that view is because, as a field, economics has failed to accurately distinguish what we actually do. Unfortunately, the blame for this should fall on us, economists, as we have failed to properly demonstrate what we do, allowing for others to use economics as cover for their opinions. Let me explain.

Economics Research, Policy and Politics

In the interview, Stewart and Thaler focus a lot of their discussion on climate change and reducing pollution. Stewart asks about what economists would recommend to deal with climate change, to which Thaler responds by mentioning carbon taxes as the solution. Stewart says that such a policy would never pass.

We have several issues occurring in this exchange, which is predominantly driven by talking about different things. Thaler responds to Stewart’s question by proposing a very good policy (a policy I also would personally support). Stewart, however, changes the question by bringing in a constraint – he’d like to hear a policy that would be politically feasible. Stewart was a bit vague with his initial question, which caused the confusion.

Economists, however, can tackle both of Stewart’s questions. If you, as a personal preference for a social outcome, want to see less pollution, economists may recommend the carbon tax policy. If you add a constraint to this preferred outcome – for example, I want less pollution but I don’t want taxes – economists may provide a different policy.

Basically, if you have a preference for a social outcome for anything involving people such as less pollution, more technological innovation, more factories, etc., economists can give you a list of policies that would achieve the stated goal. Moreover, each policy would have a particular cost associated with it. In the climate change case, it may look like this:

Carbon Tax: short/medium run things will be more expensive, which may have distributional consequences;

Subsidy: taxes need to be raised to fund subsidies; it is difficult to set subsidies to achieve desired goals;

Regulations: costly to enforce (need to create a new body); regulation evasion can be significant.

Armed with this, a politician/policy maker/voter can pick their preferred policy. None of the policies above are wrong, as long as it is aligned with the preferred outcome of a politician or individual. Economists, in their capacity as experts, should focus on how to best achieve your stated goals/outcomes (we can think of this as the ‘fiduciary’ responsibility of economists).

However, economists are also people, and they often have their own preferred goals/outcomes, which is where things get murky.

When Policy Recommendation and Personal Preferences Get Murky

The problem for economics occurs when economists or economics commentators start intentionally mixing policy recommendations with their own preferences. Unfortunately, these are rarely easy to spot.

One notable example to me is the recent proposal by New York City mayor of lowering transit cost by providing free buses. Numerous articles and comments came out criticizing the program. But the reality is that economics research is quite clear that free buses (and free transit) is a good policy to address this issue. However, the field of economics has not pushed back against the false narrative being spun around the policy.

Another topic where the policies and personal preference got murky is the debate around wealth inequality. Many economists and commentators are often very critical of any changes to taxation or the introduction of wealth taxes. These commentators often point to the costs of implementing the policy, as if the costs themselves are sufficient reason for not implementing changes. Instead, it should be the choice of the public about what costs they want to bear and trade-offs they want to undertake.1 It is not for economists to decide which policy to choose – just to inform about the cost/benefits to the best of our knowledge.

Thus, the problem for the field of economists is that many of these economists/economic commentators covertly pass on their personal preferences and views, under the guise of economics. This is why Jon Stewart ultimately viewed the field in the negative context – he’s seen plenty of headlines and news pieces, which do that, and assumed that the entire field of economics must be like this. Economists, unfortunately, ceded the conversation on what economics does and let it be usurped by fancy looking opinion pieces. We shouldn’t be surprised that an opinion like Stewart’s is out there – we haven’t done much to combat it.

What Should Economists Do?

Naturally the next question is what should economists do, to be accurately depicted.

First – an easy one – don’t pile on people like Stewart (or anyone for that matter – as mentioned by Claudia Sahm). Stewart has his beliefs and preferred social outcomes. We, as economists, should engage people like Stewart and can help explain which policies can achieve his preferred social outcomes (Thaler did a good job with this in the podcast).

Moreover, since we economists are trained to think in particular frameworks which focus on preferences, in discussions like the one with Stewart, we should make sure we understand people’s preferences over social outcomes. Too often the debate focuses on a particular policy (free buses, wealth tax, etc), which is a tool and not the outcome the policy is supposed to generate.

But what else should we do? This is where it gets harder, but economists should start a conversation about how to properly communicate what we do. As mentioned earlier, the vast majority of academic economists and commentators act in the way I described economists should. Often, however, the most vocal ones do not. I do not have an easy answer on how to deal with this. Perhaps there is a need for a centralized body/committee that can clearly present economic findings, or present how different policies will affect the economy. Or maybe handbooks (similar to the ones in medicine) that may act as solid starting points for policies.

Taking One Step at a Time

This post is one of the reasons I started Nominal News, as I have seen this problem grow over the last decade. With Nominal News, I try my best to present economics as the important and useful field it is – a field that is filled with many great and brilliant economists and educators that have designed plenty of great tools to use under different circumstances.

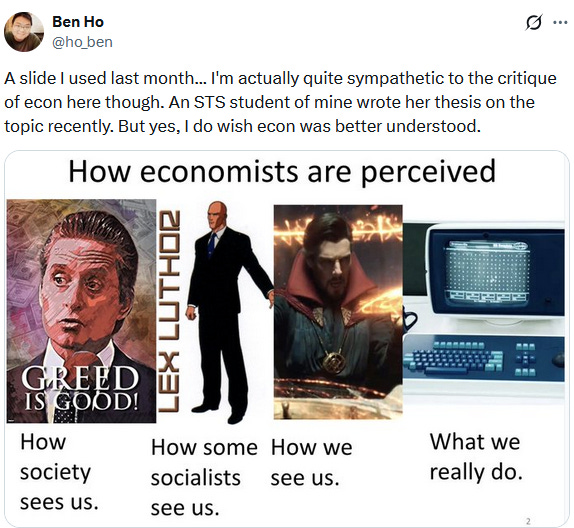

I will finish this post with a humorous post by Professor Ben Ho:

Let me know if you have any thoughts on how economics can improve its image and what I, at Nominal News, could do better?

If you would like to support us in reaching our subscriber goal of 7,000 subscribers, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

Interesting Reads from the Week

What is Critical Thinking? And why is it Important? – Abdullah Al Bahrani discusses what it is ‘critical thinking’ and what steps we can take to improve our critical thinking skills.

Why Affordability and the Vibecession Are Real Economic Problems – Mike Konczal synthesizes various strands in the affordability/vibecession debate. This includes the rising prices of essentials, higher costs to own a house, and the overall impacts of higher economic uncertainty.

AI and the Economics of the Human Touch – Adam Ozimek wrote an important piece highlighting how to approach AI from an economic standpoint, and uses historical examples to explain why technological change is unlikely to oust humans.

Moreover, even the current level of wealth inequality also has costs (for example, we discussed how wealth inequality may skew democratic processes such as the judicial system)

I feel like I had been living under a rock. I totally missed this Jon Stewart fight with economists. Thanks for bringing it to my attention.