Is The US Supreme Court Biased Towards the Rich?

A new paper shows that recent judge appointments and resulting decisions side with wealthier parties more than before.

Thank you for reading our work! Nominal News is an email newsletter read by over 4,000 readers that focuses on the application of economic research to current issues. Subscribe for free to stay-up-to-date with Nominal News directly in your inbox:

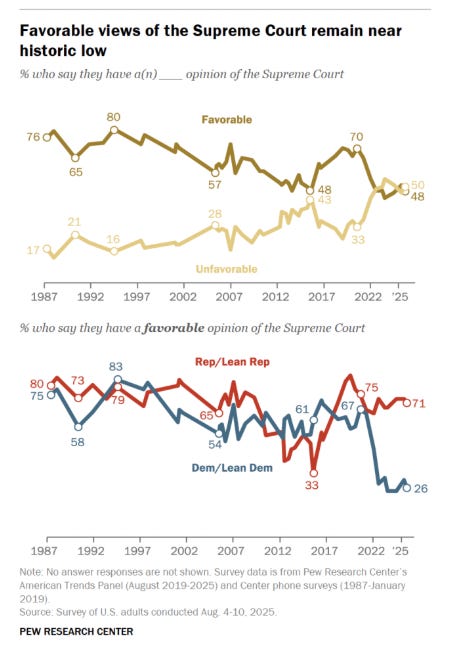

The US Supreme Court is the highest judicial body in the US, and opines on federal and constitutional issues. One unique feature of the Supreme Court is that it consists of 9 judges that are appointed for life, making judicial appointments extremely important. These Supreme Court justice appointments, which do not occur often, are usually made by the party in power, which has led to questions about the politicization of the Supreme Court. Surveys from the Pew Research Center show the public’s change in perception of the Supreme Court over time:

So is the public right in their view that the Supreme Court has polarized? Prat, Morton and Spritz (2026) (“PMS”) set out to answer that question.

Do Judges Rule in Favor of the Wealthy?

PMS started with a simple observation – a Supreme Court judge either rules in favor of the wealthier or poorer party of a court case. Different Supreme Court judges vote differently in the same court case. Many theories, involving legal interpretations, are proposed to explain this difference. However, what if instead, judges themselves have preferences over the wealth distribution? PMS decided to build a model of judges’ decision making.

Judges’ Preferences

A judge is assumed to have a preference over the ideal wealth distribution in society (in theory, every one of us has a preferred ideal wealth distribution). This preferred wealth distribution is referred to as the judge’s “ideal point”.

When faced with a court case, a judge can choose to side with the wealthier or poorer party. A judge gets utility (i.e. happiness) depending on the decision the judge makes. If the judge’s utility is higher when they side with the wealthier party over the poorer party, they’ll rule in favor of the wealthier party (and vice versa).

The amount of utility a judge gets from a decision depends on the court case specifics (i.e. it may be clearer which party should ‘win’ the court case) and how close the decision is to the judge’s “ideal point”.

Based on the above model, we can infer the judge’s “ideal point” based on their decisions. For example, if the outcome of a specific court case leans in favor of the wealthy party, while the judge rules in favor of the poor party, that would imply that the judge’s “ideal point” of the wealth distribution leans towards poorer individuals.

Judge Nominations

Supreme Court judges in the US get nominated by the majority party – the Republican or Democratic party. When the party in power gets to pick a judge, it usually chooses a judge from a pool of candidates. The pool of potential candidates is not random, as it inherently reflects the preferences of the party. In our particular case, we assume that both Republican and Democratic parties have preferences over the wealth distribution, and therefore the average judge in the pool of candidates from which they select would reflect this preference.

By looking at which judges are selected for the Supreme Court, PMS infer whether a party’s preferences over the wealth distribution have changed. For example, if judges selected by the Democratic party are more likely to side with the wealthier party in court, that would imply that the Democratic party’s preferences have moved towards the wealthy.

Now that we have the model, in order to determine how party preferences have changed, we need to look at data.

Data Collection

Contentious Court Cases

PMS, using undergraduate and graduate students, went through all Supreme Court rulings since 1953. First, PMS excluded all court cases in which the decision was unanimous, i.e. all 9 judges voted in the same way. The reason for this is that when all judges vote the same, it is not possible to infer the judges’ “ideal points” (preferences). To give a simpler example of why these court cases need to be excluded, if you and a group of friends all pick pizza when choosing dinner, then you cannot figure out from this observation who likes pizza the most (the technical term for this issue is we cannot ‘“identify” the preference).

PMS therefore focused solely on court cases where there is at least one Supreme Court judge that voted for the wealthier party and at least one judge voted for the poorer party.

Cases with Wealth Transfer

Next, PMS looked at court cases that resulted in a wealth transfer from one party to another. For example, if the case involved an employee receiving a payment from an employer, this court case would be selected for analysis, since the ruling would result in a direct transfer of wealth between the employee-employer.

Lastly, the selected court cases also had to have litigating parties that can be described as ‘wealthy’ or ‘poor’. For example, in the employee-employer case, the employer would be coded as ‘wealthy’, while the employee would be coded as ‘poor’. Court cases where this was not clear, such as a court case between two companies, were not included in the data set.

PMS laid out the protocol for classifying these cases quite clearly and imposed several checks, such as having multiple assistants classify the same cases to determine if there are any mistakes being made.

So Did Judges Become More Pro-Wealthy?

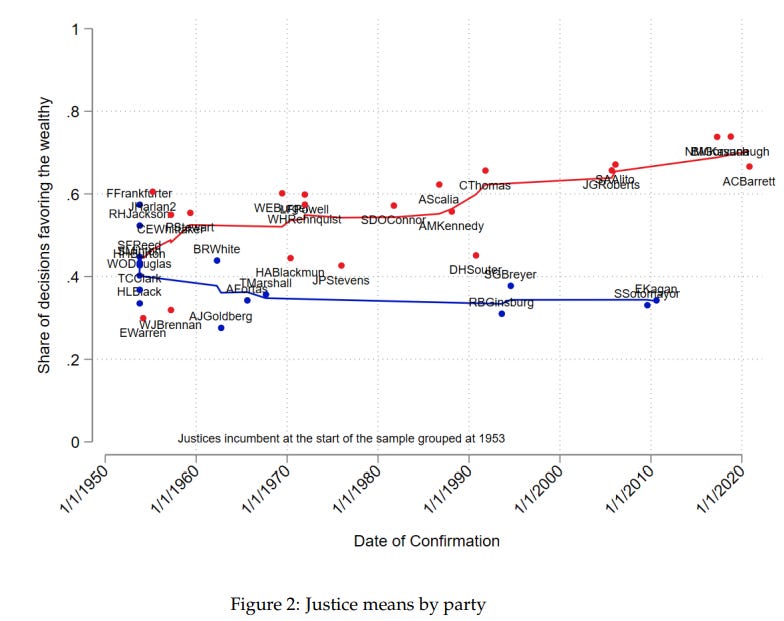

After classifying the cases, PMS looked at raw data:

The above chart shows Republican-selected judges (red) and Democratic-selected judges (blue). The y-axis shows the share of decisions made in favor of the wealthier party. The dots signify the date the judge was appointed. The line by party, at any point, represents the most recent 7-judge average (i.e. the red line is the average pro-wealthy vote share of the last 7 Republican judges).

From the graph, it can be seen that recently, there’s been a big shift towards pro-wealthy voting by Republican-nominated judges and slight fall in the pro-wealthy vote share for Democratic-nominated judges.

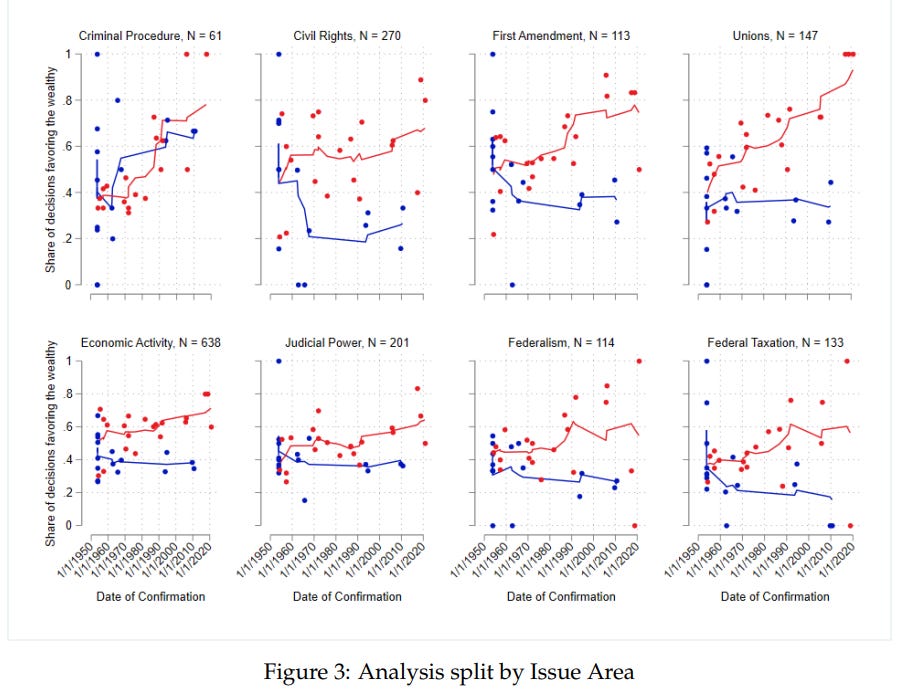

If we look at the specific type of cases (the case type is coded by the Supreme Court), the shift in voting occurs for all case types:

For example, in the top right, contentious cases involving unions have always been voted in favor of the wealthier party by the three most recent Republican-nominated judges.

Judges’ “Ideal Point” (Preference)

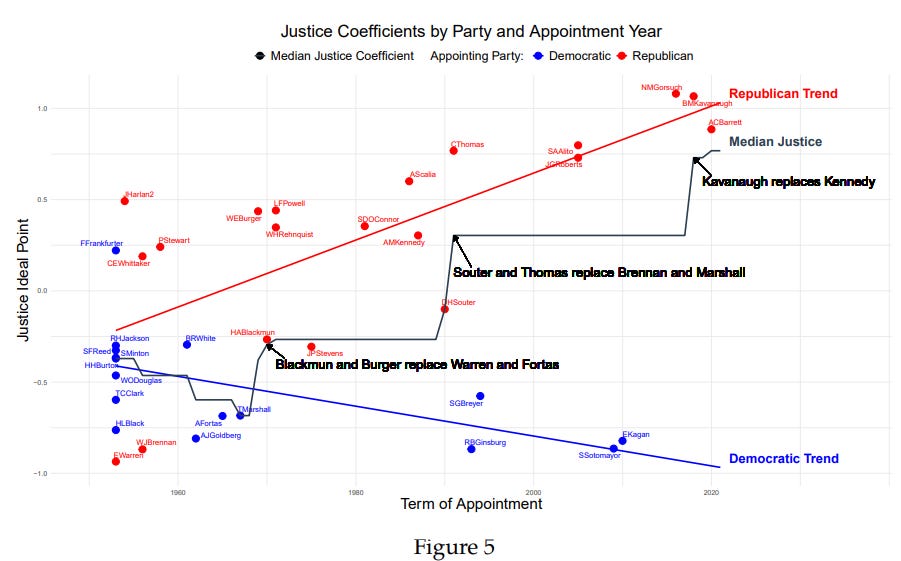

The above results show the share of decisions made in favor of the wealthy party. As mentioned in the model section, using the observed decisions, we can attempt to infer what is each judge’s ‘ideal point’ or preference for wealth distribution. The chart below shows that:

Values above 0 suggest a pro-wealthy preference, while values below suggest a pro-poor preference. The black line shows the current implied median justice preference. The implied “ideal point” of Republican nominated judges has increased significantly, which also implies that the pool of potential judges from which the Republican party selects has also become more pro-wealthy.

More specifically, the implied probability a Republican-appointed judge in 1953 would side with the wealthy party was 44% (for Democratic-appointed judges, it was 40%). In 2022, the probability that a Republican-nominated judge would side with the wealthier side is 74% (for Democratic-appointed judges, it is 27%).

What Does it All Mean?

The paper I discussed today, although political in nature, is mainly meant to demonstrate the variety of questions economic methods can be applied to. A recent post by Decode Econ talked about what is economics –

“Students arrive at class thinking it [economics] is “the study of money.” It’s not. Economics is the study of decision-making under scarcity.”

I liked this definition, and, moreover, I think that economics is more broadly the study of decision-making.

Today’s paper studied two decision processes – the decision of nominating a judge and judges’ voting decisions. As mentioned previously, judges’ decisions are often analyzed based on the legal school of thought (like textualism or originalism) judges prefer to use to interpret law. However, not all decisions by the same judge seem consistent with the school of thought. The research discussed today may explain this discrepancy, as it appears that judges’ wealth preferences may help explain why judges make different decisions in similar legal cases.

The Benefits of Clarity

Given the political nature of the question, there can be a lot of agreement/disagreement with the findings. The benefits of this paper by PMS is that the approach to the question is clearly laid out – which court cases were looked at, how the cases were coded, etc. This enables for a much more productive discussion, as any and all assumptions made by PMS are clearly stated.

One minor concern I noted is that the authors cannot control for the possibility that the cases brought to the Supreme Court may have fundamentally changed over time. For example, if in the 2000s cases, the law was more ‘objectively’ on the side of the wealthy parties, then some of the observed shift in Republican judge’s preferences may be due to the change in cases rather than an actual shift in preferences. However, some of this concern is alleviated by the fact that the Democratic-nominated judges sided more with poorer parties. Nonetheless, thanks to clarity of the model and the research, we can have such discussions.

The study by PMS is definitely not the last one on this topic and any future research will have to grapple with their findings of large shifts in judges’ decisions favoring the wealthy. Maybe this article will inspire one of our readers to tackle this issue!

If you would like to support us in reaching our subscriber goal of 7,000 subscribers, please consider sharing this article and pressing the like❤️ button at top or bottom of this article!

Interesting Reads from the Week

Article: Sebastian Galiani discusses how the Prime Minister of Canada, Mark Carney, may be utilizing his economics and game theory background in foreign policy.

Article: Kathryn Anne Edwards talks about how much is spent on immigration enforcement – $170bln – and how that compares to other US government programs.

Article: Jiaxin (Jason) He and Sam Peak discuss how preventing immigrant students from getting work in the US will result in more visas being allocated to outsourcing companies.

Awesome Post. Love how intricate and Insightful this study is.

Also, thanks for the Decode Econ shoutout!

OK -- another. Thank you for your work. It is helpful. The other thing is: money is a place-holder -- it is ALWAYS a place-holder. It NEVER has meaning in itself -- it indicates something about the people and society in which it operates. Inasmuch as this post is literally about "hoarding money", which is what wealth is, it seems to me it behooves one to discuss something about the status conferred on individuals and households in which the hoarding of money has gone to extremes. This is not true of every society -- you don't need to impinge too much on anthropology, and yet it would be good to clarify what it means that the justice system tends to prefer the well-being of those who have higher levels of hoarded wealth. Humans are status-seeking animals. If Justice is not blind in this society, its bias should be clarified -- it is not toward those who are better warriors, or better inventors, or who benefit society more -- in this society it is a bias in favor of those who hoard more wealth. This has to do with how power is wielded in this culture -- money confers the capacity to warp the system in one's favor. We covet it; our justice system defers to it; perhaps we should consider if that is a characteristic of a "good" society.