News: The US Credit Downgrade

On August 2nd, Fitch downgraded the rating of US debt from AAA to AA+. What does this mean and what does economics have to tell us about it.

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

If you would like to support us further, please consider sharing and liking this article!

Due to the recent significant development regarding the downgrade of the US credit rating by Fitch, this week’s article will go over in Part I what this means, while in Part II, we discuss whether we should be concerned about the size of the US government debt by referencing one of our previous articles.

Part I: US Credit Downgrade

What happened

On August 2, 2023, Fitch Ratings announced the downgrade of US debt from the highest AAA rating to the second highest AA+ rating, mainly citing issues around governance exhibited by the debt ceiling negotiations.

Why is this credit rating important

What are credit ratings

To understand the significance of this decision, it is important to first understand what are credit ratings. A credit rating is a measure that confers certain information about the riskiness of default (i.e. the issuer of the debt instrument fails to make a payment) of a particular debt instrument (such as a loan or a bond). For example, giving me a loan is probably riskier than giving a loan to Amazon. A credit rating, therefore, is a representation of the overall risk profile of a debt instrument. To compensate investors for taking on more risk, debt issuers typically have to offer investors a higher interest payment. It is worth adding that credit ratings can be seen as somewhat of a subjective opinion, even though they are partially determined by statistical models.

Why this rating matters

Even though credit ratings are subjective (you and I can rate debt instruments however we want), most market participants have generally accepted the ratings established by three companies – Fitch Ratings, Moody’s Investor Services and S&P Global Ratings – to be the most reliable and important (similar to how Michelin stars are treated as the most important rating of a restaurant). The ratings determined by these companies have direct financial consequences for many debt issuers. For example, if a firm would like to issue a publicly traded bond, investors typically expect the firm to be rated by at least two of these three firms.

These firms establish a letter based rating system, starting from the highest rating of AAA and going all the way down to CCC. Each of these ratings represents an approximate probability of default within the following 12 months. For example, a AAA rated debt instrument has a 12 month probability of default of less than 0.1%, and less than a 2% probability of default within 15 years.1 To establish the credit rating, the three rating agencies look at a variety of financial and non-financial factors. The rating methodology used by these companies is available to the public.

These three rating agencies are not without controversy, with probably the biggest recent scandal being their part in the 2008 financial crisis, driven by improperly rated Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs). At that time, many CDOs were rated AAA, suggesting they were extremely low risk, but ended up defaulting en masse during the 2007-08 housing bubble crisis.2 Given how unlikely so many AAA rated debt instruments could default at once, it turned out that the rating agencies were not entirely aware of what they were rating, and failed to estimate the risk properly.

However, these credit rating agencies still have a strong reputation and are heavily relied upon by investors and other market participants to gauge risk. Certain investors, such as pension funds and insurance companies, have explicit regulations that do not allow them to invest in debt instruments that are not above a certain rating. Therefore, these ratings do matter in many instances and impact not only the interest rate the debt instrument issuer has to pay, but even what type of investors would acquire the debt instrument.

Has this happened before

Yes. Fitch is now the second of the three rating agencies to reduce the credit rating of the US. S&P previously (citing governance issues) lowered the US credit rating from AAA to AA+ on August 5, 2011.

But aren’t US treasuries and bonds considered the safest

This is where the previously mentioned subjectivity kicks in. Although, there are countries and companies that are now rated higher than the US (trivia: only two companies in the world have a AAA rating – do you know which ones? Answer at the end of the post), investors can disagree with the ratings and still choose to see US debt as less risky. And investors appear to have disagreed with Fitch, with both the US debt instruments yields (i.e. price of US debt) and US Dollar not changing much, if at all.

Why did Fitch do this

Fitch cited a variety of reasons for why they downgraded the US credit rating. The main components appear to have been qualitative factors regarding governance and the debt ceiling law. In a slightly more ambiguous fashion, they cited overall fiscal issues as another contributing factor.

Part II: Government Debt from an Economic Perspective

The above discussion focused mostly on credit ratings, which are a subjective measure. Therefore, I will not opine on the validity of the credit rating change. However, from an economics perspective, we can discuss one objective measure commonly cited and used in credit ratings – the US Debt to GDP ratio. This measure informs us about how much the US has borrowed overall in relation to its yearly economic output. The measure is commonly used to determine whether the US (or any country) will be able to keep payment on its debts in the foreseeable future.

This Debt to GDP measure in isolation, however, is not actually very informative about the ability of a country to keep up with its debt payments. It turns out that there are other, better ways to determine whether the debt burden is sustainable, and what may seem like a high debt-to-GDP ratio might actually be too low. As we have written before on this topic, below is a repost of the key parts of the article discussing the question of US financial stability. The original article goes into a more in-depth discussion on what is government debt and why it is an important policy tool that really acts as an intergenerational transfer mechanism, so I do recommend checking it out. But if you are interested in only the financial stability part – continue reading here.

Financing through Debt

Before delving into what is a sustainable level of debt, let’s briefly touch upon why use debt at all. Any government spending can be broadly financed in one of two ways: either collecting revenue from its citizens, usually via taxes, or issuing debt. This debt needs to be repaid at some point in the future by the citizens, which means that tax revenues will have to be raised. This leads to a choice of “tax now or tax later”. One important factor that needs to be taken into account in this decision is the “fiscal impact”.

“The fiscal impact – is issuing debt a fiscally costly or beneficial act in purely financial terms? Basically this question focuses on whether issuing debt costs us money, today or in the future, or has no negative financial impact (colloquially known as a ‘free lunch’). For example, if the interest rate on the debt is lower than the return gained by spending this debt, the debt would have no negative fiscal impact. “

Benefits of Debt Spending

Undertaking government spending via debt can be the correct decision. In 2019, Oliver Blanchard delivered a speech (text) to the American Economic Association (video) on the issue of sovereign debt in a low interest environment. This speech has been considered to be one of the most important economic speeches in recent times, as it reinvigorated the debate around debt and deficit spending. Blanchard points out that for nearly all developed economies, the nominal interest rate for debt is below nominal GDP growth rates (which still holds true today). If we were to think of it in terms of an investment, we could borrow money to fund the investment at a lower interest rate than the return from the investment. In this circumstance, borrowing can be seen nearly as free. (In the Appendix of the previous post, I go over the mechanism explaining why such debt is not only sustainable, but also beneficial for all individuals in the economy.) This situation creates a ‘free lunch’, meaning it has no adverse fiscal, or financial, impact. Research by Mian, Straub and Sufi (2021) has shown this situation to probably be currently true in the US. To illustrate this effect numerically, today, the current nominal borrowing rate in the US (a 30 Year Treasury is at 4%) is below the GDP nominal growth rate (around 6-8%), which would imply that borrowing would be cost-less for the US. This pattern currently holds for many developed economies.

Increasing Debt – Increasing Interest Payments

Based on the above, there appears to be a growing consensus that the fiscal impact of debt in advanced economies is not that large, if any. However, Blanchard (2019) did acknowledge that if the debt interest rate return becomes larger than the growth rate of the economy. In this situation, the overall debt burden could start growing exponentially as interest payments become larger. Greenlaw et al. (2013) estimate that each 1 percentage point increase in debt-to-GDP increases borrowing costs by 0.045 percentage points. A similar effect was found by Laubach (2009). In instances where the debt would become fiscally unsustainable, there would be two ways to resolve the issue: either an increase in taxes to pay off the debt or a default (i.e. the government reneges on its debt obligation). Increasing taxes, although unpopular, is generally not too problematic, especially as it would be a one-off increase to bring the debt amount to sustainable levels. However, defaulting on debt could have potentially far wider implications.

Optimal Debt Amounts

So with both fiscal benefit and costs in mind, what is the optimal debt the US (or any country) can issue? Unfortunately, this is an unanswered question, but various attempts have been made to address it. To give an example of an official policy, the European Union has what is called a 60 – 3 rule, whereby debt-to-GDP shouldn’t exceed 60%, while annual deficits should never be greater than 3% of GDP. However, whether this is a good approach has not been determined. Blanchard, in an IMF post said about this question the following:

“So my answer to the question is, I do not know what level of debt, in general, is safe. Give me a specific country and a specific time, and I will use the approach above [Author note: described in the speech] to give you my answer. Then we can discuss whether my assumptions are reasonable. But don’t ask me for a simple rule. Any simple rule will be too simple.”

He elaborated that EU fiscal rule was probably too restrictive during the 2008 crisis and maintaining the 60 - 3 rule probably lowered consumption for all generations, making everyone worse off. Regarding the US, recent research by Mehrotra and Sergeyev (2020) suggested that the US sustainable fiscal limit could be around 150% to 220% of GDP, while it currently sits at around 120%. Mian, Straub and Sufi (2021), on the other hand, believe that the fiscally ‘free’ limit might already have been attained.

Conclusion

From an economic and fiscal perspective, there appears to be no risk of the US defaulting on the obligations in the foreseeable future. Research has shown that not only is the US debt burden not (yet) a cause of concern, but the US actually should continue to borrow if it spends the debt on productive investments, as it is a net positive investment. Therefore, it appears that the credit downgrade by Fitch was not driven primarily by economics, but possibly by other governance reasons.

Interesting Reads from the Week

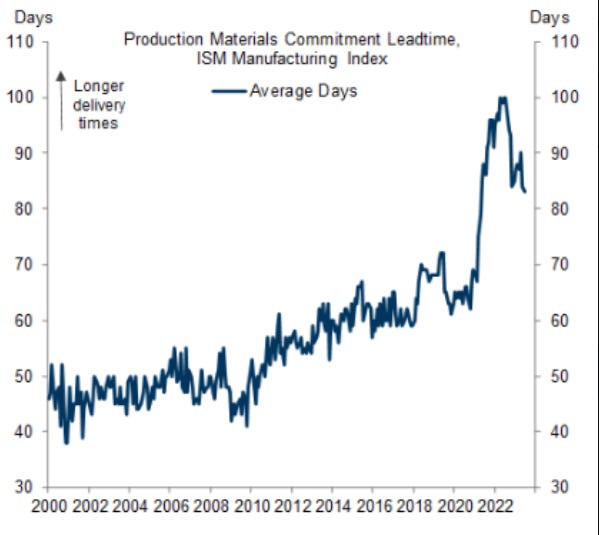

Data: Goldman Sachs shows the current lead times in manufacturing. They are still elevated, suggesting supply chain issues are still present.

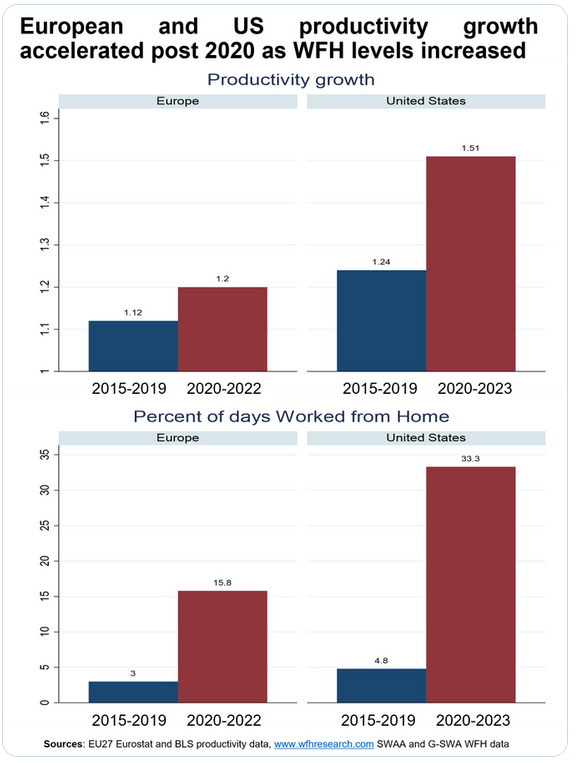

Tweet: Nick Bloom – a Professor of Economics at Stanford – shows two charts: one showing productivity growth of labor and one showing the percentage of people working from home, implying that productivity may have gone up because of remote work. Our article covers why the economic evidence currently suggests that work from home will be a beneficial and productive method of conducting work.

- – a Professor of Political Economy at Harvard and a new Substack writer – discusses the issue of ‘legacies’ (i.e. one of their parents went to the college they’re applying to), how big of an admissions boost do they get, how prevalent the issue is and how to tackle the problem of admission holistically.

- talks about how Fitbit’s success, especially with the step counter, is related to the economics of transaction costs. Additionally, how a similar product to Fitibit, made one professor skip sleep.

Cover photo by Karolina Grabowska.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

High Profile Layoffs (February 14, 2023) – how the recent layoffs in the tech sector will affect the wider economy.

Recession Talk (May 21, 2023) – news and social media are talking a lot about a recession, but the economy has been performing very well. Turns out that not for everyone – and this time it was the high income individuals that saw real income declines.

Silicon Valley Bank - A Quick Demise (March 12, 2023) – in March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank collapsed after a bank-run. What are bank-runs and how did that happen?

From a statistical perspective, there are not enough AAA debt instruments that default in order to get meaningful statistics.

The issue that occurred was how specifically mortgage backed CDOs were constructed. CDOs were a synthetic mortgage debt instrument. In brief, suppose there are 10 mortgages, each secured by a house. Buying one mortgage from a bank is a risky investment, as the likelihood the person responsible for the mortgage could default is relatively high (say 10%). However, what if instead of buying the entire mortgage, you split the full amount into five slices (tranches), with the first tranche being the most senior (i.e. the first to get repaid if a default occurs). If you just purchase the first tranche, the risk will be lower (suppose 5%). To further reduce the risk of default, you can combine these first tranches of each of the 10 mortgages into a new debt instrument that consists of 10 different first tranches. And you can slice this again into five tranches and sell the first, most senior tranche. And then repackage it with 10 other similarly built instruments. Theoretically, the probability of default should continue to fall each time. However, the issue with this theory is that it relied on statistical independence. Statistical independence in this case meant that if one mortgage defaulted it would not mean that other mortgages are now more likely to default. Mortgages were not statistically independent of each other. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many mortgages defaulted at the same time. Meaning, this slicing up of the mortgages did not actually reduce risk by that much and the probability of default of these CDOs was much higher than originally estimated.

Nice article! I think it boils down to a combination of 1) Growing political instability and 2) Unwillingness of either party to tackle the rising cost of social security and medicare. There are no good solutions here, cuts will need to be made.