Community Civilian Interventions

Many countries have issues with policing. In the US, there have been numerous high profile conflicts with police. Community interventions have been proposed as an alternative.

Thank you for reading our work! If you haven’t yet subscribed, please subscribe below:

As Nominal News grows larger, we will be able to make this a full-time project, and provide more content. Please consider supporting us and sharing this article in various social media!

Introduction

Recently, on the New York subway, it is not uncommon to see New York Police Department (NYPD) officers either at stations or in subway cars. The idea behind this recent increase in police visibility is to improve safety in the New York transit system. To give additional context, there has been a lot of media coverage regarding the increased number of committed crimes in the New York transit system, implying that people are less safe. It is worth noting that statements such as ‘less or more safe’ are also open questions (should we scale the number of crimes by population, ridership, average income, etc.) The NYPD reports information on crimes on the New York City transit system. Based on the most recent annual data for 2022, there were 4,715 crime complaints, which was a stark increase from 2021 and 2020, when there were 3,918, and 3,411 complaints, respectively. However, as those were pandemic impacted years, in 2019 the number of complaints was 4,714, while in 2018, there were 4,328. This numerical data does not demonstrate whether the New York transit has become less or more safe, since we would need to control the data for a variety of factors (we already mentioned Covid as an important factor of the recent fall in crimes). However, these numbers do give us a scale of the problem.

What I found interesting is that the NYPD is tasked to patrol the subway. In contrast, for example, in several European countries, rather than the police, one would see Municipal Police (in France and Spain), Police Community Support Officers (in UK) or City Guard (in Poland) be tasked with such patrol jobs. Usually such City Guard forces have significantly lower authority (for example, they cannot conduct arrests), but in turn deal with the more day-to-day situations related to maintaining order.

This is a very different approach to maintaining order in public. Using civilian or municipal intervention in order to deal with crime rather than increasing police presence is hotly debated in the media. Naturally, this is a question that can be answered by economics, albeit not easily.

Blattman, Duncan, Lessing and Tobon (2023) recently released a paper that looked at the question of the level of civilian government intervention in communities. Both the study design and the result of their research are fascinating – and have already been heavily misinterpreted by many! Let’s make sense of this study and its teachings.

The Experiment

Background

Blattman et al. conducted an experiment in Medellin, Colombia to study the impact of increasing civilian and government intervention on the levels of crime and governance. Many cities around the world have been attempting to deal with disorder and crime, preferably without having to resort to weapons. However, often it is the police who are the first responders to a range of everyday disputes including domestic violence, homelessness, regulatory breaches, or other civil disputes.

In Colombia, the police are a national institution – that is local governments and mayors have limited control over the police, especially regarding staffing levels, police training, and police guidelines. Thus, large cities such as Medellin, have created their own ‘alternative’ security agencies with neighborhood-level government staff dealing with local minor problems. These security agencies are controlled by the local government and deal with street disorder, domestic violence, and public space regulation. In Medellin, the agency is called the Secretariat of Security and has roughly 1 employee per 1,000 residents. In contrast, the police staffing level in Medellin is approximately 2.7 police officers per 1,000 residents.

Although Medellin is a relatively wealthy city, with a well developed bureaucracy, it suffers, just like many cities around the world, from a street gang problem. These street gangs, called ‘combos’, do not only undertake illegal activities but also provide a variety of basic services for the local community such as security, dispute resolution, and debt collection. These services are often provided by combos for a fee, or weekly taxes, called vacunas.

Intervention

Blattman et al. worked with the municipal government of Medellin and identified 80 low to middle-income neighborhoods that would participate in the experiment. One very unique element about this experiment was that the municipal government of Medellin allowed Blattman et al. to conduct a randomized control trial. Out of the 80 neighborhoods, only 40 were to receive the intervention of an increased civilian government expenditure, while the others would receive the same level of government service as before. This type of experiment design is very similar to medical trials, where one group of individuals gets the intervention (medical treatment), while the other group – the control group – does not. The difference between these two groups would then be attributed to the intervention. In social settings, these types of experiments are extremely rare, as institutions such as local governments would be worried about any political costs of such a decision.

Blattman et al., with the assistance of the local government of Medellin, conducted an intervention on 40 neighborhoods, shown on the map of Medellin below:

The intervention (or treatment), that was to be conducted by the staff and activities of the Secretariat of Security, had two main components:

The 40 neighborhoods would be prioritized by the city’s current main service agencies. This included quicker access to dispute resolution officers for problems between and within families, as well as priority responses to basic services requests such as garbage pickup and street light repairs.

Each of the 40 neighborhoods received a full-time ‘liaison’ – a local government representative that would assist in linking people with government agencies, identify public service issues, as well as assist with business and family dispute resolution.

The overall intervention can be viewed as an increase in the provision of typical municipal services. Thus, the experiment can determine the impact of such an increase in the provision of municipal services. The intervention in these neighborhoods lasted for 20 months. In terms of how large this intervention was, Blattman et al. estimated that street-level attention to problems was increased 60-fold (measured as the increase in liaison officers per block, which went from 1 liaison per 540 blocks to 1 liaison per 9 blocks), while the attention from the municipal government to the particular neighborhood increased two to three fold.

Results

The outcomes Blattman et al. focused on measuring were quantifiable ones such as the instances of crime and number of emergency calls stemming from each neighborhood, and also certain qualitative, survey-based measures, such as reported governance (whether citizens believe the local government responds to issues) and legitimacy (whether citizens trust the local government to resolve issues, especially in comparison to combo street gangs).

The overall results from this study were surprising – on average, there was no impact on any measured outcomes. Crime and emergency calls did not decrease, while reported governance and legitimacy did not improve either (it actually may have decreased!).

This has been interpreted as evidence that increased community interventions do not work and are a waste of resources. However, Blattman et al. assessed this data through another perspective. Prior to the intervention, Blattman et al. collected information on the level of local government capacity and presence in all the neighborhoods. Blattman et al. assumed, prior to the experiment, that in neighborhoods where the local government was weak (i.e. limited municipal interventions and participation), the impact of additional local government intervention would be the highest since even the slightest increase in civilian program expenditure would result in a large positive impact.

The results, on the contrary, showed the opposite! In areas where the local government had a strong presence and was seen as legitimate, the returns to the intervention were high and positive. Crime fell by 28%, emergency calls reduced by 41% and government legitimacy increased. In neighborhoods with weak local government presence, there was no positive impact. Part of this was driven by the fact that in these neighborhoods, the new liaison officers failed to deliver on promises they made to the communities. The liaison officers were also less likely to show up to meetings, did not refer problems to the necessary agencies, and did not address the issues such as fixing street lights. Many citizens of these neighborhoods were alerted about the local liaison officer meetings too late, did not see any of the new intervention employees or even know about the increased intervention scheme. The graph below shows the relationship between strength of local government and delivering on promises, after increased intervention.

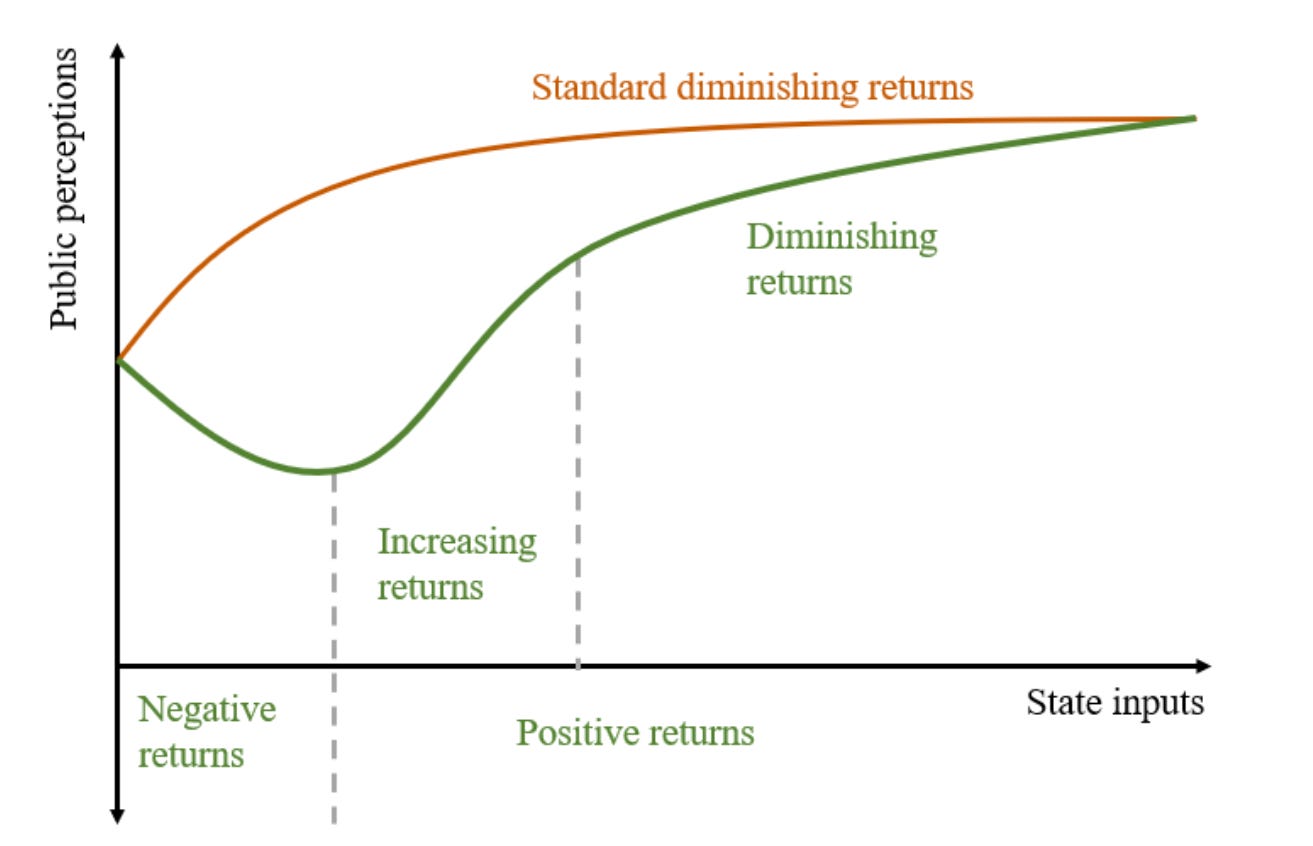

Based on these results, Blattman et al. believe that for these weak local government presence neighborhoods, it might take a longer time of consistent intervention in order to change the perception of the local government. At first, the local intervention in these neighborhoods may not generate any returns (or even generate negative returns when factoring cost), but over time, as local government presence strengthens, positive returns from additional local government intervention can occur. This is known as the S-pattern of returns, shown below.

Whether this is true or not, would require additional research.

Conclusion

The study conducted by Blattman et al. has a lot of valuable insights not only related to the question of local government intervention, but also methodological issues regarding interpreting data and experiment design.

First, the headline results stemming from this study can be deceiving. The reason there was no impact of increased local government intervention was due to the fact that in high local government presence areas, the impact was positive, while in low local government presence areas, the impact was negative. Therefore, the average came out as zero. But clearly, once we condition on local government presence, the study showed that there are positive impacts from increasing local government presence. By just focusing on the headline results, policymakers can end up making wrong decisions.

Secondly, the above also shows how important it is to consider a wide variety of factors prior to conducting a study and when evaluating study results. Had the authors not collected information on local government presence prior to the study, we would erroneously conclude that increased local government interventions have no impacts.

Regarding the overall impact of increasing local government intervention, this study shows that it is a complicated issue. In neighborhoods that have the weakest local government presence, which city officials would typically want to target the most to improve, initial investments in local intervention might not pay off for a while. Improvements might only be visible after many years of consistent government intervention, and that any initial lack of any improvement might be expected. However, in areas that have higher local government presence, additional investment appears to have large positive impacts on crimes and government legitimacy. Thus, in such areas, additional investment would improve outcomes immediately.

Naturally, this finding can impact local government decisions – if a mayor of a city wants to see immediate results to improve their electoral chances, they will invest in areas that already have high local government presence and spending. On the other hand, underinvested areas would continue to be neglected since they require multi-year continuous commitments, forever keeping these communities under-invested.

Interesting Reads from the Week

Tweet/Paper: a recent paper that looked at rising profit margins by industry and compared them to the level of inflation in the industry found no relationship. My quick response to why, although interesting, this does not disprove ‘greedflation’.

Tweet: ‘greedflation’ was trending and many still misunderstand that economic theory shows that ‘greedflation’ can occur. The question isn’t whether it can, it’s whether it did.

Tweet/Paper: related to last week’s article on work requirements, Jason Cook and Chloe East just released a paper that found that two thirds of SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) applicants do not work outside their home due to barriers such as disability and caregiving responsibilities, thus not meeting work requirements. Separately, many individuals that are denied SNAP benefits fail to provide all the necessary documents rather than being ineligible for SNAP.

Tweet/paper: a psychology paper by Orveli, Kross and Gelman found that using the word “you” increases the resonance of an idea. For example, songs with “you” are more liked!

Substack Note: a thread on maternal mortality during and after pregnancy. This is the first time the US CDC has released data on mortality after pregnancy. The rate in the US is unfortunately at an all time high with 32.9 deaths per 100,000 – for context, this is worse than Syria’s mortality rate.

Cover photo by Dave Romain

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy the following ones from Nominal News:

Marriage Preferences and Gender Outcomes (March 26, 2023) – how partner preferences impact the glass ceiling.

Early Child Investment - Child Tax Credit (January 15, 2023) – the benefits of the expanded child tax credit to society.

To Compete or Non-Compete – why non-compete clauses do not solve any issues, but only create costs.